To even try to explain the proliferation of assets and connectivity in the built environment without looking at the underlying political and economic drivers is thus a rather futile exercise. One can, of course, go on hoping that these sensors and routers will be deployed to humanize and personalize national and local bureaucracy—yet this seems like a rather naïve aspiration given that bureaucracy itself is increasingly being taken out of the government’s hands. Once privatized, this humanizing rationale disappears as if it never existed: A privatized toll road—the quintessential example of smart infrastructure built to “sweat the asset”—has no need for humanism.

~ Evgeny Morozov and Francesca Bria

There it is a definite social relation between men, that assumes, in their eyes, the fantastic form of a relation between things.

~ Karl Marx

Introduction

Since its launch, the Smart City Mission (SCM) in India has attracted a great deal of critical commentary. The criticisms include, but are not limited to, the ambiguity of the smart city concept and its indefinite goals; the gulf between the programme’s seemingly inclusive rhetoric and its data-centric, technologically driven interventions; the infringement on privacy due to the emphasis on data collection and monitoring; the problems of implementing digital technology in a fragmented urban governance system; the elitist, unequal and exclusionary conception embedded in technological solutions; and the depoliticising effects of the governance structure mandated by the Mission.

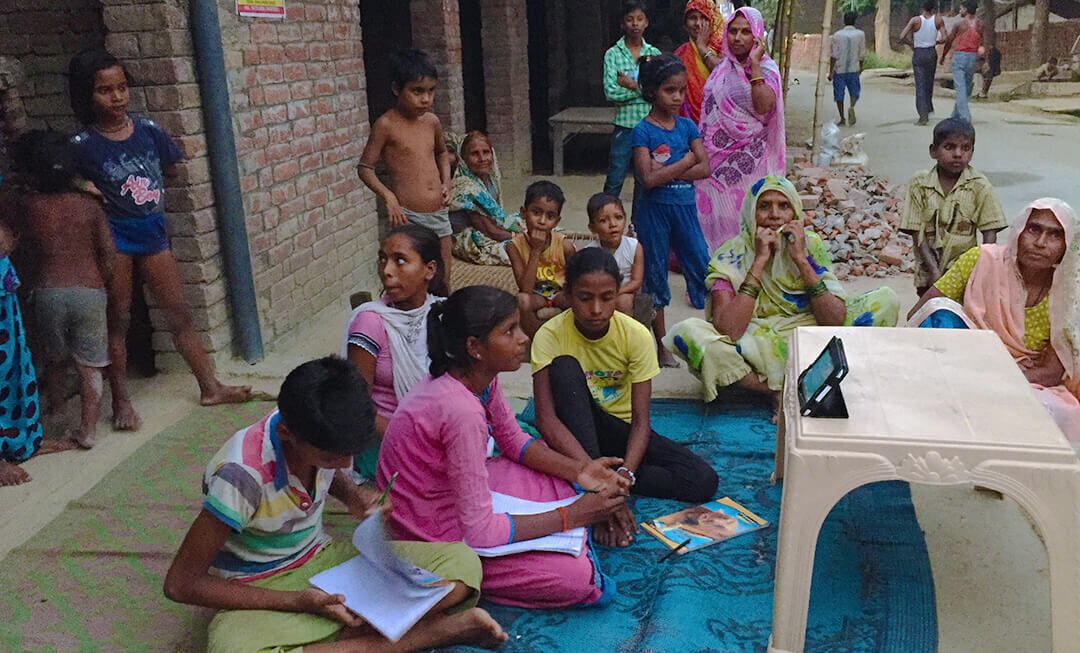

Although commentators have frequently highlighted the absence of clear objectives of the SCM, there is a general consensus that the Smart Cities concept involves the application of digital technologies “to bring greater efficiency in the functioning of different urban systems” and “leveraging cloud-based IoT [Internet of Things] sensors, actuators, video cameras, and other intelligent devices to connect components across the city to receive, analyse and manage data in real time.” Even if we take the Smart Cities concept at face value, it is not difficult to recognise that for most inhabitants in Indian cities, basic urban infrastructure and services are unavailable or woefully inadequate – a gap which cannot be meaningfully addressed or improved through the use of digital technology. What good is a digital app that indicates bus arrival times when the number of buses are insufficient and declining? What is the advantage of digitising solid waste management when its coverage is partial and disposal practices are unsustainable? Even in their benign form, digital technologies may provide marginal improvements in sectors such as traffic management and mass communication, but can do little to address structural urban problems. In cities around the world, the degree of municipalisation of urban functions and State intervention in the provision of public goods and services – serviced land and adequate housing, sanitation, education, health care, public transport, environmental conservation, etc. – are a reflection of the extent to which dominant classes have been forced, in the face of social mobilisation, to accommodate certain interests of the working people in the urban system. That is to say that the methods to address the major urban questions in cities have long existed, and in part even institutionalised as basic rights. But these are actually class issues, and the failure to adopt these methods are an expression, not of practical problems, but of political choices exercised by dominant class interests. If anything, the promotion of digital technology as an apolitical solution for urban problems is a class politics – of interests that drive global consultant firms, technology providers, big bureaucracy, and vendor networks – that seeks to simultaneously obscure the nature of urban problems as well as the social-class dimension of ‘smart’ urbanism. It is this latter theme that I aim to explore in this article.

The SCM has promoted a corporate-style restructuring of urban governance, with a greater role for private consulting firms, integration of monitoring and surveillance technologies to expand the privatisation of urban development and service provision, and an extensive involvement of the private sector investors and contractors as beneficiary partners of the revenue streams generated from its various projects.

In other words, although the SCM rhetoric suggests technology–infusion as a radical response to India’s urbanisation challenges, the programme is closely aligned with the general trend of privatisation-enabling urbanisation policy in recent decades. Its distinctiveness lies in (a) the introduction of a new ecosystem of intermediary private actors that supply information and digital technology tools and platforms for service delivery; and (b) the expansion of the scope of large financial and project management consulting firms in shaping the urbanisation agenda, influencing urban policy and monitoring urban renewal. In what follows, we will first look briefly at the origins of the SCM approach and look at some trends and cases from its implementation over five years. The second part of the essay argues that the SCM is a part of the evolution of what can be called the toll-booth model of urbanisation: the outsourcing of traditional urban government functions to the hands of state-private corporate entities, the expropriation of public assets and the privatisation of public goods and services, and the creation and policing of exclusive networks and enclaves – in order to generate opportunities for land and access rent extraction (tolls). Typically operationalised in the form of ‘Public-Private Partnerships,’ it involves engaging private consultant firms for financial and technical ‘expertise’, schemes and projects that facilitate the monetisation of public land (often through the expulsion of the poor for capturing land value), creation of quantifiable techniques of service delivery (to collect user charges), and outsourcing operations to private entities (to collect service payments). The toll-booth model of urbanisation is based on State-enabled policies of value extraction rather than value creation; its social milieu is a professional-managerial class of officials, experts, consultants, contractors, even NGOs – driven by and trading in ‘specialisation’ and ‘expertise.’ Deeply suspicious of public processes and popular politics, its proponents seek to delegitimise them through the valorisation of ‘competition’, ‘efficiency’, and ‘participation,’ where success and failure of policies and programmes are measured by revenue outcomes, as opposed to social outcomes.

Evolution of the Smart City Mission

The BJP’s manifesto for the April 2014 general elections highlighted a normative vision of cities as “symbols of efficiency, speed and scale” and promised, among other things, the building of 100 new cities if it were elected to power. The Modi government’s Smart City Mission (SCM) was launched a year later, in June 2015. Despite the profusion of excitement over the new programme, it was a substantially tempered version of a much more ambitious commitment of greenfield cities. The SCM was unveiled as a program of urban retrofit, upgrading and renewal that aimed to promote institutional restructuring, digital solutions and ‘innovative’ area-based projects in 100 cities selected based on a countrywide competition.

Before the SCM Guidelines were announced in June 2015, the Ministry of Urban Development floated draft ‘Concept Notes’ of the proposed scheme that attempted to define its purpose and delineate its contents. Meanwhile, seminars and conclaves on the smart city idea were organised around the country, featuring high-profile speakers from the Government and private sector. The candid remarks of the head of a private economics research firm in one such seminar in Mumbai were instructive. Smart cities, he explained, will necessarily be “special enclaves” with “good urban planning, good infrastructure and good technology,” and the main problem is how to keep people out of them. Since the existing laws do not allow for such exclusion, these enclaves will need to rely on the “only two ways to keep people out of any space – prices and policing”. If these enclaves are built as new cities, they will need to be protected from the masses, and their example can then be extended to existing cities through a “spate of urban reforms.” Smart cities will move away from the “command and control hierarchies” to a participative local democracy that is “totally networked and e-enabled” with an empowered elected mayor at the helm. In other words, the economist envisioned the smart city as a decentralised and participative techno-utopia for property owning citizen-consumers who alone count as worthy of being its members.

The draft concept notes produced by the Government during the formative period of the SCM seemed, in contrast, more restrained in tone, and more grounded in legal and political-economic realities. Nevertheless, elements of the privatisation-enabling ‘urban reforms’ agenda as desired by the private sector were evident even in these documents. The Concept Note of September 2014 articulated the spirit of these ‘reforms’ through the principle “Governance by Incentives rather than Governance by Enforcement.” It then went on to list the various “instruments” that make a smart city: use of clean technologies, use of Information and Communications Technology (ICT), participation of the private sector, citizen participation and smart governance. Private participation would allow the Government to “tap on to the private sector’s capacity to innovate” and private sector service delivery would help achieve “higher levels of efficiency.” The extensive use of the ICT would be a “must” to ensure “information exchange and quick communication.” This technology would then allow for “citizen consultation” and a “transparent system” to “rate different services” in order to improve performance. Furthermore, the use of the ICTs in public administration would overcome the “fragmented” setup of ULBs (Urban Local Bodies).

The revised version of the Concept Note released in December 2014 added “parastatal” alongside “ULBs,” and by the time the SCM Guidelines were released in June 2015, the formation of a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) – a limited company incorporated under the Companies Act – was made a necessary condition for scheme implementation. The Guidelines allowed private sector or financial institutions as minority shareholders in the SPV, and joint ventures and partnerships with the private sector for the implementation of projects. Returns were expected from commercial development and user fees for urban services.

The selection of cities for the Mission was based on a two stage competition, and the selected cities were required to prepare proposals to compete for a higher position in the various rounds of funding disbursement. Each city would be given Rs 500 crore from the Central Government, and an equal amount would have to be provided by the state government or the city. This fund would be channeled through the SPV. The SCM identified two types of proposals, (1) area-based development and (2) pan-city initiative. The first could involve either one or a mix of three types of “strategic components”: (a) retrofitting (for an area more than 500 acres), (b) redevelopment (for areas more than 50 acres), and (c) greenfield or city extensions (areas more than 250 acres). Since the focus of the SCM was predominantly the area-based approach, the SCM Guidelines mandated a pan-city initiative for every selected city, defined as the “application of selected Smart Solutions to the existing city-wide infrastructure” which would make “all the city residents feel there is something in it for them also.”

Experience of the Smart City Mission

Notwithstanding what the city residents may have felt about the Mission, the record of fund allocation reveals that there was in fact very little in it for them. A 2021 study reveals that among the 100 cities selected for the SCM, 81 per cent of the funds were allocated for the area-based development (ABD) projects. The study found that among the 75 cities for which information is available, the ABD projects on average impact less than 5 per cent of the total city area. In larger cities, the area impacted by such projects was as low as 1 per cent, or even lower. Similarly, in large cities, only an average of three out of 100 people benefited from the ABD projects. As the study notes:

The skewed investment towards the development of elite enclaves reinforces existing power geometries and social and spatial inequalities rather than eroding or reconfiguring them. These pilot urban renewal ventures fuel the debate on the possible class inequality effects of policies oriented towards creating smart cities by prioritizing certain areas over others, deepening intra-city inequalities against principles of democratic and sustainable urban development processes.

In response to a question posed in the Rajya Sabha, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) submitted the proposed expenditure in various sectors of the SCM. The largest sectoral investment included area development (20.3 per cent), mobility (16.5 per cent), economic development (12.2 per cent), and ICT (10.8 per cent). These fall predominantly under the ABD component, and constitute together approximately 60 per cent of the spending. On the other hand, solid waste management (2.4 per cent), social sectors (2.4 per cent), storm water drainage (2.4 per cent), waste water / sewerage (4.5 per cent), roads (3.9 per cent), and water supply (5.3 per cent) – or what could be considered basic services – comprised only 20.9 per cent of the total spending. As an analysis by the Centre for Policy Research pointed out, the five major development categories among the top sixty cities under the SCM, namely, transportation, energy and ecology, water and sanitation, housing, and economy, constitute almost 80 per cent of the budget, and are similar to the project headings undertaken under the earlier Jawaharlal Nehru Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM).

Nevertheless, the perception that the SCM’s lack of attention to sectors such as basic services, basic infrastructure and housing is evidence of its failure as a programme is based on a misunderstanding of its objectives. The SCM, and particularly its ABD component, were in their very conception based on carving out a distinct territory that stands apart from the rest of the city – an environmental equivalent of the top tier of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs – by developing enclaves that aspirational citizens are fit to inhabit, as opposed to development that addresses the mundane needs of the city’s undistinguished inhabitants.

The sectoral profile of the SCM spending shows that the thrust of urban development continues to be real estate development (residential and commercial), transport infrastructure, and urban beautification projects. When scrutinised at the level of each city, a richer picture emerges of the priorities and impacts of the programme.

Take Bhopal, which was chosen as one of the first 20 cities to be funded under the SCM. The Bhopal proposal dedicated approximately four times the sum for its ABD component as for its pan-city component (Rs 3,440 crore and Rs 875 crore respectively). Since the first location selected for the ABD was resisted by residents on environmental grounds, the location was shifted to TT Nagar – with 90 per cent of land in Government ownership. Prepared by the Tata Consulting Engineers and premised on a new land monetisation policy, the ABD was planned as a high density mixed-use district with amenities, commercial areas, a stadium and approximately 15,000 housing units, 3,000 of which were for Government employees. The project involved the relocation of 586 informal commercial units to a newly constructed Haat Bazaar, and displacement of approximately 400 slum units to another site through another scheme, the Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana (PMAY)/Housing for All. This means that rehabilitation of livelihoods and homes affected by the project was not part of the SCM budgets or plans.

It is evident that smart city proposals have aimed at the containment or relocation of the urban poor, and have relied on other schemes and authorities to address the social consequences of their proposals. This was specified in the SCM Guidelines itself as “convergence” between schemes such as AMRUT, Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), National Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana (HRIDAY), Digital India, skill development, etc – all launched by the incumbent government since 2014.

Nevertheless, while rehousing of slum dwellers could be passed on to other schemes/programmes, no such “convergence” has been forthcoming for informal livelihoods. Street vendors have perhaps been the group most adversely affected by smart city projects, especially since a major focus of the SCM has been transport infrastructure and street beautification – typically an excuse for removing vendors. A quick survey of the street design drawings and images of smart city proposals in various cities shows that vending areas/stalls are rarely, if at all, considered a vital part of the street. This is despite the existence of the Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending (PLRSV) Act of 2014, that is meant explicitly to protect the rights and livelihoods of urban street vendors, and aims to “promote the vocation of street vendors.” The Act makes makes it illegal to evict a single street vendor unless all “natural markets” in the urban area are surveyed and a street vending plan has been prepared. It also requires all natural markets to be automatically converted into vending zones, and states that if vendors need to be relocated, due process must be followed, and the two pretexts of overcrowding and sanitation cannot be used. Implementation of PLRSV could have been made a precondition for receiving Central Government funds, or “convergence” with any new scheme, since the law has been partially or entirely circumvented by local authorities everywhere in the country. Instead, the SCM has been the pretext to violate PLRSV, since SCM projects have sought either to evict vendors, reduce their numbers considerably, or relocate them to specific ‘vending zones’ – without due process, and in many cases away from where they were based.

In Patna, for instance, street vendors took to the streets in 2023 because “their livelihoods have been destroyed in the name of smart city beautification.” In Puducherry, after the municipal corporation outsourced daily rent collection to a private firm, vendors have faced harassment, and now shell out five to 10 times more than they used to pay. In Pune, a survey by students of TISS Mumbai pointed out that smart city beautification projects precluded street vending:

The road from Parihar Chowk to Breman Chowk is currently being redesigned as a part of Smart City Pune project. The layout of the road plans to address traffic problems during peak hours and parking problems. Moreover the layout has a well designed space for pedestrians, a cycling track and sitting arrangements around trees, Wi-Fi, vertical garden, etc. However, this road has been declared as a No-Vending Zone.

The Agents: ‘Smart’ Contractors

The most significant aspect of the SCM, as noted by many, is the privatisation of urban services, by outsourcing them to contractors and vendors. In consultant-speak, smart cities need to develop a well-developed ‘supplier ecosystem.’ In line with the ‘reforms’ orientation of earlier programs such as the JNNURM and UIDSSMT, the SCM has further enlarged the scope of contractualisation as the central logic of urban administration and service provision. The hierarchy of the ‘players’ in the techno-urbanism market according to analysts consist of technology providers, engineering firms, system integrators, government agencies, and startups.

As Gaurav Dwivedi documents, contractor firms played a central role in Bhopal’s pan-city projects. These include: the chartered bike system – operated by the Chartered Speed Company; the Smart Parking project – outsourced to the joint venture company of Civic Smart and Mind Tech (which was further sub-contracted to “petty contractors”); the Bhopal Plus app (a payments portal) – implemented by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC); and Smart Roads (with hi-tech poles and street lights) through PPP, among others.

Another empirical study on the experience of SCM implementation points out that 72 of the 100 Smart Cities have at least one project in the solid waste management (SWM) sector, and digitalisation in this sector is one of the most common projects adopted under the SCM. The study looks at the case of Mangaluru, where the municipal corporation had earlier (in 2015) engaged a contractor, Antony Waste Handling Cell Private Limited, to manage the collection of waste. The ‘digitisation’ project under the SCM was “decided, designed, and introduced” by the Smart City SPV; it engaged a Bengaluru based vendor, Trinity Mobility Pvt Ltd, which in turn outsourced some of its tasks to other vendors. Trinity Mobility provided training to Antony Waste’s employees to adopt digital tools such as GPS tags and QR codes. The new vendors introduced by the SCM therefore created a ‘dual institutional framework’ – on the one hand, the municipal authority and its contractor, and on the other, the SPV and its vendors. It brought in a new chain of technology vendors within the context of an already contractualised waste management system, complicating it further.

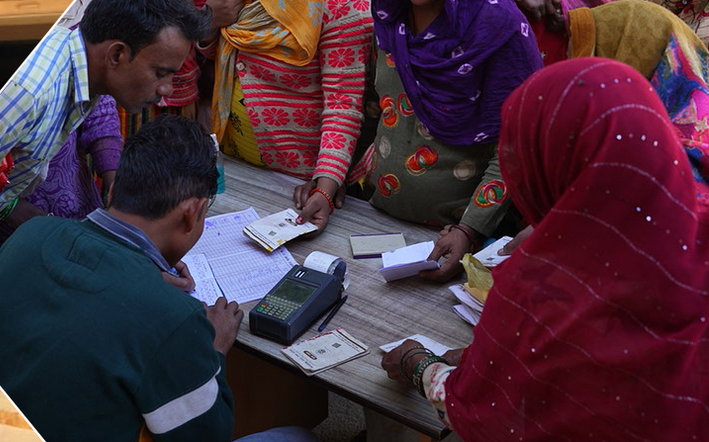

Even so, what is benefit of introducing digital technologies to the solid waste management sector? In the case of Mangaluru, digitisation by the SCM vendor involved installing new GPS devices on the vehicles collecting waste, which allowed them to be tracked (these vehicles, incidentally, were already equipped with such devices). It also involved installing QR codes at each premise where waste is being collected, and workers were instructed to scan these QR codes to record that the premise had been serviced. Workers were burdened with the additional task of scanning codes in addition to waste collection, encountering numerous difficulties. It is obvious that digitisation does little to improve the coverage and accessibility of waste-management services, or the sustainability of its current practice. Its does, however, serve two purposes: (1) providing information to the ‘consumers’ of the service, and user data to the vendor; (2) monitoring and surveillance of service delivery, to achieve a more effective form of labour control.

A key intervention of the SCM has been the creation of Integrated Command and Control Centres (ICCC) that function, in the words of the MoHUA Minister Hardeep Singh Puri, “as a city’s nervous system where digital technologies are integrated with social, physical, and environmental aspects of the city, to enable centralised monitoring and decision making.” The ICCC website describes these as “the hub of innovation as they facilitates [sic] effective management of city operations, exceptional scenarios and disaster mitigation using information and communication technologies.” The establishment of these Centres has relied on technology firms as vendors and Project Management Consultants. The Manguluru ICCC was implemented by a Chennai-based firm, Madras Security Printers. Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE) was instrumental in setting up these centres in Bhopal and other cities of Madhya Pradesh, while reports suggest that Larsen and Toubro (L&T), IBM and Honeywell have been involved in setting up such Centres in other cities.

Yet, we may ask: what is the purpose of such ICCCs? Even in celebratory accounts, their most lofty achievements are traffic management, surveillance and law enforcement. The Patna ICCC, the Times of India explains, “is going a long way in helping police regulate traffic and keep an eye on rule violators in the city.” The Additional Municipal Commissioner of Bhubaneshwar argued that the ICCC “enables real-time monitoring of numerous city services” and by “centralizing information and decision-making, it plays a pivotal role in providing efficient services, improving governance, and catering to the needs of Bhubaneswar citizens effectively.” In Madhya Pradesh, it will enable the “state administration to monitor and administer multiple city civic utilities and citizen services across seven cities in the state through a central cloud.”

A more credible explanation of the true purpose of the ICCCs was provided by the Finance and PPP Expert of the Smart City Mission Management Unit: monetisation of data. The data aggregated by these Centres, we are told, hold “immense potential to be leveraged” that can help the city economy, by making different businesses more effective and creative/ innovative. The goal is to foster innovation and stimulate business activity and to “raise revenue for contributing to operation & maintenance cost” of the infrastructure created by the City SPV.

One of the alleged objectives of the ICCC, disaster mitigation, was put to test by the 2020 Covid pandemic. Unsurprisingly, as a monitoring and policing instrument, the ICCC aided the enforcement of the indiscriminate and unplanned government lockdown. Around 45 cities repurposed these facilities as “war rooms” for “lockdown enforcement”, “tracing and tracking”, and to raise public awareness about “appropriate Covid behavioural norms.” In Madhya Pradesh, ICT and Geographic Information System (GIS) tools were deployed to “create containment zones,” carry out “surveillance of isolation centers,” as well as “detection and violation of masking and social distancing.” But despite the enthusiasm for these repressive techniques, some observers of the SCM cities were unconvinced:

Surat experienced widespread labour unrest, where the workers were abandoned by the administration during the lockdown. Indore saw absolute chaos during the second wave, with the highest number of Covid deaths in the state. While Varanasi, located in eastern Uttar Pradesh, witnessed the gruesome spectacle of corpses floating in the Ganga. None of these Smart City Integrated Command and Control Centres (ICCC) proved to be effective and contribute meaningfully.

We may also wonder how much this networked infrastructure of urban surveillance actually serves regular police work. Even here, notwithstanding the ‘theatre effect’ of security achieved by innumerable CCTV cameras hooked on to every building and cell-phones pinging every tower – the technology in fact seeks to replace human systems with a privatised ensemble of hi-tech objects, making security less public and more elusive. On the occasions on which the police do use digital technologies, they need to rely on contractors who have the data. These contractors collect data to monetise it different ways, not to facilitate standard police work. The central purpose of digital technologies is to create avenues for private profiteering, and to deal with any kind of resistance that results from the failure or breakdown of that system – rather than providing security to the public. The public is the enemy, to be exploited and controlled, not served.

The specific purposes of the private corporate sector and the State with regard to surveillance, while complementary, are very distinct. The former seeks to maximise data-gathering in order to analyse and shape/control patterns of consumption and labour at large, to its profit; the latter seeks to narrow its data-gathering to target specific political threats. Activists may worry about the ‘big brother’ state violating individuals’ privacy with every camera and every cell-phone, but state surveillance systems are hardly organised as an all-seeing all-knowing apparatus. State surveillance is strategic rather than pervasive, and targeted rather than universal – its purpose as a repressive tool is to maintain and protect a predatory system, and to deal with resistance by tracking down specific individuals and networks.

The Authors: ‘Smart’ Consultants

In February 2018, The Caravan reported an anonymous letter written by a bureaucrat to the Prime Minister, alleging “rampant corruption” in the India operations of the multinational consulting firm, KPMG. The author of the letter claimed that the firm exercises its influence over key Government officials by hiring children or relatives of many “senior IAS and IPS officers” from the Central and state governments. It argues that one job in the firm is equivalent to a lifetime salary of Rs 40 crores; so hiring a relative of a high level official “is nothing but a bribe of Rs 40 crores.” It went on to list many bureaucrats serving in key Government posts whose relatives were offered positions by the firm. This practice translated into concrete outcomes for KPMG, in the form of large consulting assignments in Government projects such as HRIDAY, Swachh Bharat, AMRUT, Smart Cities, and more. The letter also mentioned the role of the KPMG and the United States government in pushing US firms such as “Cisco, IBM, Dell, HP, Honeywell, United Technologies, Otis, etc” into the Smart Cities program, “at the cost of Indian firms.” The letter continued:

The malaise is not restricted to only KPMG but is spread across what is popularly called the Big Four Consulting firms, who have practically infested all our governments. A quick investigation will reveal that government projects worth over Rs. 300,000 crores are being handled by US consulting firms and that at least 100 top bureaucrats have their children or relatives working in these consulting firms.

Two among the many areas of concern indicated in this letter – the hiring practices of big-tech consultants and the sidelining of local providers – were reported in the media in the case of the Bhopal Smart City. In October 2019, the former Principal Secretary in the Urban Development Department in Madhya Pradesh was accused of manipulating norms of a tender worth Rs 300 crore to favour Hewlett-Packard Enterprise (HPE) and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), arousing suspicion, as the official’s son was a senior associate in PwC. Soon after, the state-owned company BSNL, which had bid lower than HP & PwC for the project, wrote to the Government alleging a “major conflict of interest” as PwC was the consultant for the bid, and HPE was a bidder – and it was known that the two firms “are partnered to develop the smart city application.”

Whatever the veracity of the claims, these reports are noteworthy in terms of what they reveal about the shared moral and cultural universe of the economic and bureaucratic elite. The allegations provide a glimpse into the interconnected networks of the top bureaucracy and the upper echelons of consultant firms, a social milieu from which they derive social stability as well as mobility. Nevertheless, it is no secret that large consulting firms, particularly the ‘big four’ of KPMG, Deloitte, PwC and Ernst & Young (E&Y), as well as some others, have played a significant role in shaping India’s urban policy and governance. This involvement was explicit in the Ministry of Urban Development’s “Concept Notes” during the formative stages of the Mission:

Over the last few months, several professional agencies made presentations in the Ministry highlighting different aspects of what constitutes a smart city. Globally renowned consulting companies like KPMG, PWC and Accenture have presented a wide range of features that are the hallmark of a smart city. Leading experts like Dr Keshav Verma have also presented some of the important features of a smart city. Leading IT companies like IBM have made presentations on the role that IT can play in developing smart cities…Given the knowledge base that exists in such agencies, as well as others in the country, it would be important to involve them actively in the process of designing smart cities hand holding the city/ state government in coming up with visionary plans. It is therefore proposed to take advantage of this capability in a structured manner. Detailed guidelines for doing so will be developed.

The SCM Guidelines noted that the Smart City plans will be “quite challenging” and therefore states and ULBs will require the “assistance of experts.” Technical assistance support, it stated, could be obtained by “hiring consulting firms and engaging with handholding agencies.” Large consultants like Cisco, PwC and Deloitte even produced framework reports on the SCM to help set the Smart City agenda. In 2016, the Ministry released a list of 48 shortlisted firms that could be hired for the preparation of Smart City proposals as project development and management consultants (PDMCs). The list included management consultants such as CRISIL, Deloitte, KPMG, PwC and McKinsey; technology firms such as Cisco, SoftTech Engineers, and Infosys; financial institutions such as Genesis Finance; and property consultants such as Jones Lang LaSalle and Knight Frank. As a SCM review report by KPMG explains:

By default, these consultants were meant to address all tasks of the SPV ranging from conceptualizing the projects, creating detailed project reports and other preparatory studies, and also engaging in supervision during the construction process. In essence, the PDMC was meant to be an extended arm of the SPV itself. The fees to the PDMCs are typically payable from the provisions for administrative and other expenses.

In other words, the entire process of Smart City planning was outsourced to consultants, giving them unprecedented scope to define problems, set priorities as well as shape outcomes. The shift that such “collaboration” represents is glaring: instead of public sector regulation of market actors, cities are entrusted to private actors, that are “focused on short-term outcomes, financial benefits, and profit driven asset management” hand-holding and guiding (while asset-stripping and hollowing out) the public sector. It has produced “a hydra-headed organisation” that combines “permanent public employees and a parallel new bureaucracy” made up non-state consultants.

A former Chief Secretary of the Government of Madhya Pradesh found the long-term implications of this shift “more bothersome” than its short term consequences of setting up multiple overlapping authorities:

It seems to be the beginning of governance of the city being outsourced as a part of the larger design of outsourcing even the governance activities to market players. There is no dearth of pro-capital economists and specialists that passionately argue for outsourcing many more functions of governance. They don’t seem to be satisfied with the strong almost predominant control or influence of the corporate on government in almost all democracies. Such projects are small, gentle and covert steps towards privatisation of what we essentially consider to be the powers and functions of the government.

A Political Economy of Smart Urbanism

Through the SCM as well as through other urban ‘reform’ programs, we are witnessing in Indian cities the increasing privatisation of government functions, the stripping away of public goods, the setting up access barriers for ‘innovative’ means of value capture, the monetisation of public land, and the subcontracting and contractualisation of basic services. This suggests that we must look at the “underlying political and economic drivers” that are shaping the built environment, from within and outside specific government programs like the SCM. In a city like Mumbai, that has not been a part of the SCM, the toll-booth model of urbanisation has been long in the making.

Take for instance the city’s Brihanmumbai Electric Supply and Transport (BEST) system. Municipalised soon after Independence, the BEST was set up on a cross-utility financial model, with the surpluses from its electricity operations making up for the deficits in the transport division. The privatisation of electricity – facilitating the entry of private service providers such as Reliance and later Adani into the power distribution sector – and subsequent court orders broke up the cross-subsidy model. Left on its own, the transport division saw its deficits piling up. These so-called ‘losses’ and ‘inefficiencies’ of BEST became the pretext for bringing in private operators into the transport division, and today close to two-thirds of the buses operated by BEST are run by contractors.

The consequence has been a disaster, for commuters as well as transport workers – with poorly maintained buses catching fire, long queues of commuters waiting for buses, discontinuation of long routes, a depleted fleet, diverted buses, and failing operations. Meanwhile, thousands of BEST employees are without work, because BEST doesn’t have the buses to employ them.

Behind the BEST’s new initiatives, such as electric buses and a new digital ‘Chalo App’ for commuters to buy tickets online and ‘track’ buses, is its outsourcing of core operations to contractors. The latter stand to benefit from a whole range of measures (subsidised purchase of buses, free parking in BEST depots, payment for distance covered as opposed to passengers carried, monopoly operation on the allotted route, etc.) to extract a revenue stream from the utility. Furthermore, the privatisation of BEST and downsizing of the workforce has opened the door to the sale of BEST’s assets, particularly urban land. In 2017, the BEST engaged the ‘big four’ firm PwC to prepare a report on the monetisation of BEST land. According to the report, 126 hectares of land could yield a revenue of Rs 1,800-2,200 crores, or an “enhanced” revenue of Rs 5,170 – 6,160 crores. What is at stake is the prospect of public and private capture of revenue streams from urban land.

Or take urban governance. The SCM required cities to set up SPVs to implement the Smart City Plans, and private firms could be minority stakeholders in the SPVs. For Dharavi redevelopment in Mumbai, the Maharashtra government has set up a SPV led by Adani Properties, with the private entity holding 80 per cent of the revenue and voting share, and the state government parastatal (the Slum Rehabilitation Authority or SRA) left with 20 per cent. This is the first time in India that a planning authority will be controlled by a private firm, giving a developer firm state-like powers. Even better for the Adani SPV is the handing over of approximately 240 hectares of Dharavi land (most of which is publicly owned) for the project, along with 115 hectares of salt pan lands, and 26 hectares of land in Mulund (also publicly owned) to be monetized by the company. It will enjoy additional largesse in the form of relaxations in premiums, and new rules that provide the SPV with a fixed rate and assured market for the sale of Transferable Development Rights.

The influence of large consultants on Mumbai’s urban development and planning policy is also well known. In 2003 a pro-corporate think-tank commissioned McKinsey and Company to prepare a “comprehensive vision” for the city, and Mumbai’s administrators have adopted many of the consultant’s recommendations. Other consultants, such as CRISIL, have also prepared ‘road maps’ for the city, and the World Bank has always been a major influence in Mumbai’s policy circles. All these consultants have peddled similar pro-corporate, pro-privatisation ‘visions’ for the city. Infrastructure planning and development in the city is to a large extent undertaken in PPP mode, and planned and justified by large consulting firms – for instance, Mumbai’s Coastal Road project was planned by E&Y. The same firm is also working closely with the state government to implement a Central Government loan scheme for street vendors, and is appointed as a consultant for drafting a new housing policy for the state of Maharashtra.

Although these are scattered examples, it is clear that urban policy and governance in Mumbai have come to rely increasingly on certain forms of technology for surveillance and service delivery; on financial contracts in place of institutions; on private developers, contractors and vendors as the agents of urban development; and on large consultants as the authors of urban transformation – an institutional environment of a State-facilitated rentier economy.

Conclusion

Smart urbanism is one manifestation of a longer project of privatisation, outsourcing, and value capture, now dressed up as phone apps, QR codes, CCTV cameras and GPS tags. It presents gamified participation as more consequential than urban democracy, private goods as more efficient than public goods, hi-tech policing as more effective than urban regulation. The question still remains: what does the term ‘smart’ imply?

The SCM Guidelines provides an illustrative list of 21 ‘smart solutions’ without specifying what makes them ‘smart’ – or for that matter, what problems those ‘solutions’ seek to overcome. Cisco explains that to be ‘smart’ is to utilise “information and communications technology (ICT) and the Internet to address urban challenges.” Even in literature generally critical of Smart City interventions, it is taken for granted that the term ‘smart’ implies technology infusion. In other words, ‘smartness’ is assumed to be a feature of a technology or a type of technology – endowing it “with self-contained, mysterious, and even magical powers to move and shape the world in distinctive ways.” The designation of a bike, a pole, a phone, a road, or a waste bin that is connected with a central server as ‘smart’ is a form of what Marx termed as fetishism: where particular social relations between people “assume the fantastic form of a relation between things.” Fetishism depicts technology as the outcome of an autonomous technical and economic process, where the best ‘solutions’ to all manner of problems have emerged along the linear path of continuous progress. It conceals the socio-technical context, power relations, institutional structures, social values and cultural habits that determine their shape and form, and their selection and elimination. Most importantly, it obscures the interests and intentions of social groups that stand to benefit from the development and deployment of particular kinds of technology. And therefore, it is necessary to underline the social-class dimension of ‘smart’ city governance and decision-making controlled by a professional-managerial class of ‘experts’ rather than through the contingencies of the traditional institutions of democratic government. ‘Smart’ denotes technocracy, not technology.

Footnotes