The decade between 2004 and 2013 heralded a slew of rights-based legislations on the back of social movements crusading for transparency and accountability. These legislations were designed to transform the nature of the citizen-State relationship, by making some fundamental requirements of life such as work, food, nutrition, and education into legally mandated rights. The articulation of these rights was drawn by reading together both the Fundamental Rights and the Directive Principles of State Policy of the Indian Constitution. For example, the right to work got enshrined as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA). Food security and the nutritional requirements of women and children were built into the National Food Security Act (NFSA). Both NREGA and NFSA need to be seen as a legislative fruition of Article 21, the right to life. The formulation and language of rights are critical from the perspective of citizenship, and there is much to celebrate in how rights-based legislations have been pivotal for the poor.

The last one and a half decades have also seen an extraordinary rise in internet technologies. To this end, the ‘Digital India’ campaign, launched by the Union government under the BJP, is one of their much publicised governance initiatives. Its vision is to transform India into a digitally empowered society and ‘knowledge economy.’ To realise such a vision, there has been a massive thrust for digital technologies in every sphere of our lives. For instance, as per the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), in November 2023 alone, there have been nearly 11.2 billion UPI (Unified Payments Interface) transactions amounting to more than Rs 17 lakh crores. According to the champions of the digital economy, advancements in technologies like UPI have had a transformative impact in financial transactions for businesses.

The preoccupations of governments

For governments, key preoccupations with regard to the implementation of welfare schemes include achieving policy objectives efficiently at scale and reducing corruption. And digital technologies appear to be promising in this regard. Many Indian states and ministries at the central level have created various digital platforms to identify rights and entitlement holders, disburse cash, and monitor the efficacy of various programmes. The 12-digit biometric based ID called Aadhaar has been a primary tool for the Union Government in this regard. During enrolment for Aadhaar, demographic details of individuals along with their biometric fingerprints and iris scans are collected, as they are considered to be unique identifiers of individuals. These details are stored in the Aadhaar database. Aadhaar is meant to provide every resident with a unique ID and, so as to eliminate ‘ghost’ and ‘fake’ individuals from welfare rolls. The Jan Aadhaar initiative in Rajasthan, the Parivar Pehchan Patra (PPP) database in Haryana, and the Smart Pulse Survey of the state of Andhra Pradesh etc are some examples of state level identity databases.

Most social security programmes are implemented through some scheme specific Management Information System (MIS). For cash transfer programmes, some financial platforms are also integrated with the respective MIS. These have been branded under the catch-all umbrella phrase Direct Benefits Transfers, or DBT. A total of 314 schemes from 54 ministries have been classified as being ‘DBT schemes’ by the Union Government. Indeed, the 2022-23 Economic Survey presents a glowing picture of the progress in DBT using Aadhaar: “In a very short time, the country has seen a great multiplier effect on social and economic growth through the different uses of digital enablement led by the humble mobile phone and the Aadhar number– targeted beneficiary identification for various benefits, provision of healthcare and education services and financial inclusion.”

Such ebullience needs to be balanced with caution. There is much to celebrate in terms of the successes of technologies like UPI, but one needs care in assessing DBT because, while the UPI is for business transactions, DBTs are meant to ensure that the rights and entitlements of citizens are honoured. In this article we focus on the nature of automated digital exclusions that violate the rights of people.

Exclusion: error or policy?

Any policy implementation, digital or paper-based, can result in ‘inclusion errors’ and ‘exclusion errors’. Inclusion errors happen when somebody not eligible for a scheme such as rations wrongfully or stealthily avails of rations. Exclusion errors happen when somebody eligible for a scheme does not get it, owing to administrative mistakes. Inclusion errors are costly for the Government, as they result in leakage or loss of funds. Exclusion errors, on the other hand, result in denial of rights, the consequences of which can be as grave as death (Johari, 2018). Despite the lopsided consequences of the two forms of error, governments tend to pay more attention to inclusion errors than exclusion errors. The burden of proof of exclusion errors inevitably falls on the citizen, and it can be a monumental task for a rural citizen to negotiate with the hostile State apparatus to prove that the Government has wrongfully excluded her/him from accessing rights.

With the advent of digitisation, one observes that not only do exclusions persist but also that they are getting automated. For instance, the Right to Food campaign documented more than 100 starvation deaths between 2015 and 2019, many of which happened because rights-holders were unable to meet the stringent digital conditions such as Aadhaar linking with their ration cards. Even well-meaning officials on the ground are unable to correct such automated exclusions, owing to the centralised control of the programme design. Another compelling recent news report by the Reporters’ Collective is illustrative. It shows how numerous living old age pensioners were marked as dead in the Parivar Pehchan Patra (PPP) database of Haryana. The PPP links several government databases to create a family’s socio-economic and demographic profile, and automates the eligibility check of welfare schemes. For most programmers, eligibility conditions are equivalent to coding the criteria. However, it does not account for spelling and demographic variations across administrative databases in rural India, and this can be a source of massive inconsistency.

The stated objective of a digital intervention may be at odds with reality. In withdrawing rations, for example, the most common kind of fraud is quantity fraud. Quantity fraud happens when, instead of giving 5 kgs of rice, the dealer gives only 4 kgs. Every person who goes to a ration shop knows of this practice, and also knows that Aadhaar cannot curb quantity fraud because Aadhaar is meant to detect identity fraud. And yet, despite high chances of exclusions owing to technical glitches, the Centre has mandated Aadhaar-based biometric authentication to withdraw rations. As noted earlier, introduction of such digital conditionalities may only exacerbate exclusions without tackling the main problem.

Rich source of information, but not for workers

Let us now look at NREGA. In NREGA, work has to be provided to the applicant within 15 days of her/him demanding it, failing which the worker is eligible for an unemployment allowance. In case wages are not paid within 15 days of completion of the work, the worker must be paid a delay compensation for each day’s delay. The entire process has been digitised, from the work demand to the payment of wages, and everything in between with respect to worksite measurement and so on. In fact, the real-time MIS has become the de facto engine for the running of the programme.

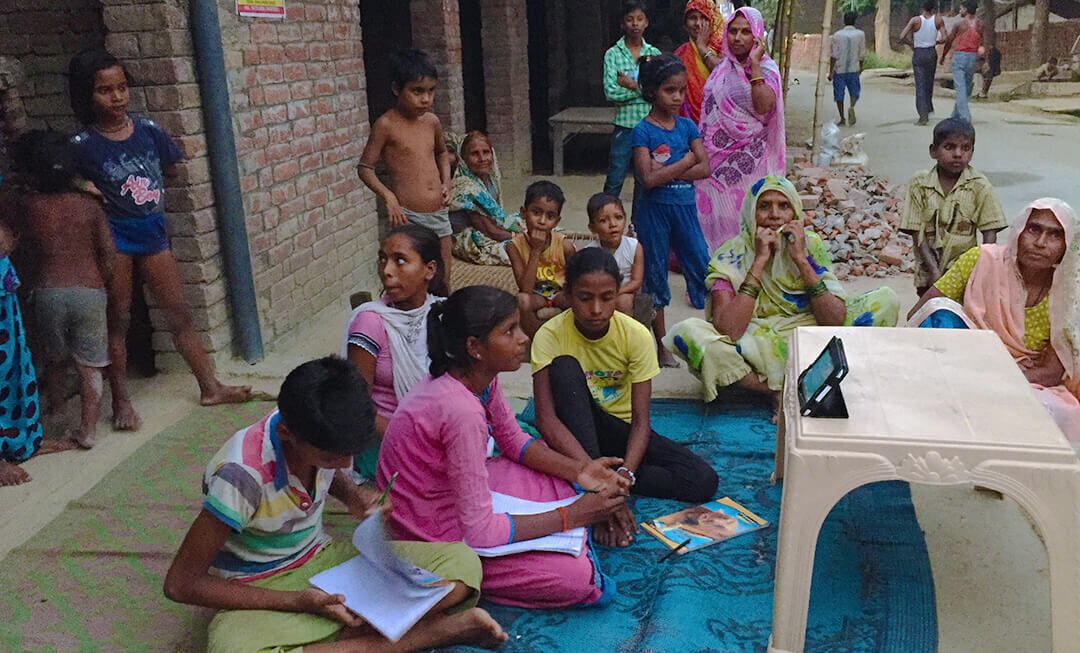

While the MIS has rich details, there is no easy-to-understand format available for workers to access their own information. What is missing, but important from the workers’ perspective, is to have information printed, akin to a pamphlet, on at least the following: (a) the dates on which they worked (b) the muster roll number in which they worked (c) the name of the work (d) the amount of wages earned and (e) whether the wages are credited or not. If these pieces of worker-centric information were available for workers in print (offline) at the panchayat bhavan, then much of workers’ anxiety would be allayed. Indeed, based on precisely such an intervention by LibTech India in Telangana, a randomised control trial (RCT)-based evaluation by Das, Paul and Sharma (2023) shows substantial reduction in wage delays and trips made to access wages in the treatment villages compared to the control villages.

There is ample evidence demonstrating how the NREGA MIS has increased opacity and has violated workers’ rights (Buddha, Dhorajiwala and Narayanan, 2021). For instance, upon presenting the work demand, the workers are supposed to get a dated receipt. Until funds are available, work demand is not entered on the MIS. A cursory check on the MIS will show how the work starting date is almost always just a day or two after the work demanded date for most workers. Moreover, even this suppressed work demand is actually under-estimated. See Ajith and Narayanan (2023) for details.

Workers in the digital labyrinth

Seamlessness and removal of intermediaries have been oft-repeated claims regarding digital technologies. But this is not true in practice. The work flow begins by generating a muster roll which is a document containing the list of workers with their job card numbers, their work IDs and the dates. The Act mandates that copies of muster rolls must be available at the worksite for inspection by anyone. But this has steadily undergone a transformation. In 2021, the government launched the National Mobile Monitoring System (NMMS) to record attendance of workers at worksites. Each worker’s photograph has to be geo-tagged and uploaded with time stamps twice daily at the worksite. Payment of wages to workers depends on the number of days (s)he has worked. If a worker worked for 5 days, but owing to network failures or problems with the app, the attendance is only uploaded for 2 days, the worker is denied wages for 3 days of work that (s)he has actually done. Moreover, since there is no back-end authentication mechanism to match the worker’s ID and her photograph, the app fails to meet the very aim of curbing corruption for which it was purportedly introduced. See Lalwani (2022), Buddha and Tamang (2022) for more.

Upon completion of a muster roll of work, invoices called Funds Transfer Orders (FTOs) are electronically sent to the Centre. As per official guidelines, in order to make the wage payments within the mandated 15 days, the states should send these invoices to the Centre within eight days of completion of a muster roll of work. Subsequently, the Centre needs to transfer the wages directly to the bank account of workers within seven days of receiving the invoices from the states. However, timely payment of wages in NREGA has been a persistent concern. Evidence suggests that insufficient allocation of funds has led to massive delays in wage payments without any payment of delay compensation (Narayanan, Dhorajiwala and Golani, 2019). Even the Ministry of Finance has acknowledged this and the Supreme Court has strongly reprimanded the Centre on this. While researchers and practitioners estimated that the allocation for the year 2024-25 should be at least Rs 2.71 lakh crore, the actual allocations have only been Rs 86,000 crores. As a percent of the GDP, the allocations have been steadily declining in the last four years despite rural distress (Gupta and Tamang, 2024). With the current allocation, if all the NREGA job card holders demand work then only around 20 days of work in a year could be provided per household.

The rule of Aadhaar

Aadhaar has been a central technology in NREGA. In NREGA, Aadhaar is said to play three roles:

- Verification of Job Cards: Seeding the Aadhaar numbers of the workers with the NREGA job card which means authenticating her job card details with the Aadhaar database. Authentication is successful only when all the details including spelling and gender in the job cards match with those in the Aadhaar database.

- Directing Payment: Making the payment through the Aadhaar Payment Bridge System (APBS), wherein Aadhaar is the financial address of the individual. For this, Aadhaar must be linked to her bank account and the Aadhaar number of each worker must be mapped correctly through her bank branch with a software mapper of the National Payments Corporation of India, which acts as a clearing house of ABPS. The transferred cash gets deposited to the last Aadhaar-linked bank account.

- Withdrawing Money: Withdrawing money from private individuals running Customer Service Points (CSPs)/ banking kiosks or through Business Correspondents (BCs) through Aadhaar based biometric authentication. This requires the individual to seed their bank account with their Aadhaar number. This is known as the Aadhaar-enabled Payment System (AePS).

Until recently, there was a choice between paying wages using the traditional account-based system or using the Aadhaar-Based Payment System (ABPS). Account-based systems are like NEFT payments that use a worker’s name, her account number, and IFSC code. From January 1, 2024, after five extensions, the Union Government has made wage payments in NREGA through the ABPS mandatory. There is no official document that precisely articulates what constitutes ABPS but based on experience and interaction with officials at various levels, one can infer that the ABPS constitutes a combination of the processes outlined in roles 1 and 2 given above.

Contrary to the authorities’ claims that these steps will enhance efficiency, a detailed study found that there is no statistically significant difference in the time taken to process wage payments through ABPS and through account-based systems; similarly, there is no difference in the likelihood of a payment facing rejection. (Bheemarasetti, De, Narayanan, Saboo and Tamang, 2023.)

On the other hand, the perils of such a move have been widely researched, documented and reported. Incorrectness in any of the processes in roles 1 or 2 for ABPS means that the worker is denied work, does not receive wages or is not paid in her preferred account. In order to meet targets of seeding Aadhaar with job cards, officials have resorted to en masse deletions of job cards. The job cards of many alive and willing to work individuals have been deleted by marking them dead. In response to a question in the Lok Sabha, the Ministry of Rural Development said that there has been a 247% increase in job card deletions in the last financial year compared to previous years. In the last two years alone, job cards of over 7 crore workers got deleted. As on January 11, 2024, out of a total of 25.6 crore registered workers, only 16.9 crore workers are eligible for ABPS while all of them are eligible for account-based payments.. See Buddha and Tamang (2023), Nair (2023), Bhaskar, Sarkar and Singh (2024) for more details. For a case study on the resultant loss of work or wages, see (Barnagarwala, 2024).

Length of the last mile

The concerns regarding AePS are part of a larger basket of concerns bracketed as ‘last mile challenges.’ From the perspective of many officials, their job is done once the payment is transferred. However, the hurdles and challenges faced by rural workers in accessing their own hard-earned money from rural banks, commonly referred to as ‘last mile challenges’, are often ignored. In most of rural India, there is only one bank branch for about 20-odd panchayats, and each branch has fewer than 10 staff members. There are state to state variations in this, with the bank penetration being better in the south Indian states compared to the north. On any given day, the banks get overcrowded. A visit to a bank to withdraw means that workers have to travel many kilometres and the entire day is just spent withdrawing money. That day’s potential employment and earnings are therefore lost. On many occasions, they have to make multiple visits to the bank. So, effectively, to withdraw 1000 rupees, conservatively speaking, they may have lost 250 rupees. To remedy this, over the years, the governments have tried various payment disbursement methods such as using the AePS. In theory, they don’t have to visit banks any more, but there lies the rub. While these can be convenient alternatives, there is no accountability framework for AePS. Consequently, people’s basic rights are often trampled: Such as having to pay bribes of commissions to the agents of Customer Services Points (CSP) or Banking Correspondents (BC), not getting their passbooks updated, making multiple trips because their fingerprints didn’t work, or there being no electricity, or there being a network connectivity problem, etc. Unfortunately, there is no place that workers can go to get these problems resolved, as there is no mechanism to redress these grievances. Moreover, the data on the number of attempts to biometrically authenticate and the extent of authentication failures are not public. A report by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) from 2022 states “UIDAI did not have a system to analyse the factors leading to authentication errors.” A detailed study and recommendations based on wide consultations and many years of field work to deal with last mile challenges can be found in LibTech India (2020). This study includes a primary survey of 1947 respondents from Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand and Rajasthan. Some numbers from this study may be illuminating:

- An estimated 42 per cent in Jharkhand and 38 per cent of people in Rajasthan took more than four hours to access wages from banks. In comparison, this was just 2 per cent in AP.

- An estimated 18 per cent of bank users were denied wages and asked to visit a CSP/BC instead.

- About 45 per cent of the bank users had to make multiple visits for their last withdrawal while an estimated 40 per cent of the CSP/BC users had to make multiple visits due to transaction failures.

- An estimated 40 per cent of CSP/BC users faced biometric authentication failure at least once in their last five transactions.

- One in three respondents had to pay commissions to the CSP/BC to withdraw wages.

- While all the bank and post office users were issued physical passbooks, about 56 per cent of all those who opened accounts at CSPs/BCs were not issued passbooks. 57 percent of the respondents reported that their passbooks do not always get updated.

- More than two-thirds of the time, workers were denied the facility to update passbooks due to overcrowding at banks, or because bank officials asked workers to come back later.

100 per cent of the post-office users reported that their passbook always gets updated on withdrawals.

The push for Aadhaar has extended to children too. In 2021, the Union government launched the Poshan Tracker, a centralised platform, to monitor all nutrition initiatives. As per Union government circulars, Aadhaar updating of rights-holders — including children — in the Poshan tracker is mandatory, and subsequent Central funds for supplementary nutrition to states are being made contingent on this (Tapasya, 2022). According to the Supreme Court, children cannot be denied their rights for lack of Aadhaar. Even if it is the case — as claimed by the Government — that only the Aadhaar number of mothers needs to be authenticated at Anganwadis, such a move indicates that the Union government does not even trust children and pre-supposes them to be either ‘fake’ or ‘ghosts.’

Needed: not a KYC, but a Know Your Rights framework

An important conception behind rights-based legislations was for people to improve their political capacities and ability to make claims on the State. This is central to activating citizenship. However, a centralisation zeal, aided by digital technologies, has rendered local State actors to be outposts of a central command, thereby disempowering them. Such a move has further widened the gap between the rights-holders and the State, atomising the rights-holders, as a result of which they are unable to build solidarity networks. The dialogic nature of citizenship has been transformed to a transactional one, while simultaneously diluting traditional accountability structures. Earlier, workers could collectively demand accountability from local State actors, but now the baton of accountability is passed on to the computer.

In summary, while challenges may seem many, the solutions are not necessarily obscure or impractical. Post offices exist, and have the potential to be strengthened and integrated with the architecture of right-based legislations and service delivery. However, they have been allowed to wither away. To understand and mitigate last mile challenges, it would be prudent to form a forum comprising representatives from the Government, banks, and civil society organisations to meet once a quarter in each district. To improve transparency, one needs to use a flashlight projecting upwards towards the administration. For this, it is imperative to have strong legal safeguards for digital systems with decentralised and time-bound grievance redressal mechanisms. This is likely to make higher level administrators answerable to right-holders and more aware of the functionings on the ground. Instead of thinking of workers or ration card holders as customers or beneficiaries, the need is to think of them as citizens with rights. To this end, there is a need to move away from a ‘KYC’ framework to a ‘KYR’ (Know Your Rights) framework. Technology can be harnessed well when the foundational aspects of programme implementation are in place.

Some of the following thoughts are premised on NREGA, but can easily be translated to other schemes. In NREGA there is a huge gap between the required number of field staff and the number of available field staff. For example, after completion of a muster roll of work, the engineers are expected to finish their measurements at worksites and upload them in the Measurement Book. This must be completed within four days, so that the electronic invoices can be generated at the block. But across the country, each engineer is expected to oversee the work in about four panchayats. Each panchayat can have multiple villages and each village can have multiple worksites. On some occasions, one engineer is expected to complete measurements of more than 80 worksites in four days. This can be unreasonable and can be a recipe for corruption. Improving staff strength and state capacity here can ease the burden on staff, reducing the need and chance for corruption.

NREGA wages are lower than minimum wages in many states. Delays in wage payments, low wages, technological hurdles and opacity will only discourage workers from participating in the programme, resulting in a slow poisoning of an Act that has remarkable possibilities. We are caught in a vicious trap. When strapped of funds, officials resort to two types of rationing. They either give many days of work to a few households or a few days of work to many households. Either way, the rights of many are in peril. Introducing more digital systems cannot solve the core problem of insufficient funds which is a political decision. What is needed is political will manifested through sufficient allocation and administrative will, paying close attention to minimising exclusions. Needless tinkering with digital technologies will only exacerbate the complexities and serve to slowly poison the functioning of public programmes.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to RUPE for insightful comments on an earlier draft. The views expressed are personal and do not reflect the views of the institutions I represent.

Footnotes

Bibliography

- Ajith, Nanditha and Rajendran Narayanan, “The demand for MGNREGS is unmet”, February 7, 2023, The Hindu

- Barnagarwala, Tabassum, scroll.in, “How Aadhaar is strangling MGNREGA in a Maharashtra district and pushing workers to migrate”, https://scroll.in/article/1062358/how-aadhaar-is-strangling-mgnrega-in-a-maharashtra-district-and-pushing-workers-to-migrate

- Bhaskar, Anjor, Arpita Sarkar, Preeti Singh, “To Link or Not to Link”, Economic & Political Weekly, Vol.59, Issue. No. 1, 06 Jan, 2024

- Bheemarasetti, Suguna, Anuradha De, Rajendran Narayanan, Parul Saboo and Laavanya Tamang, “MGNREGA as a Technological Laboratory: Assessment of wage payment delays for Aadhaar-based payments and impact on delays due to payments trifurcation by caste”, (2023), August 29.

- Buddha, Chakradhar; Dhorajiwala, Sakina; and Narayanan, Rajendran, “Can a machine learn democracy?” (2021). AMCIS 2021 Proceedings. 8. https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2021/social_inclusion/social_inclusion/8

- Buddha, Chakradhar and Laavanya Tamang, “The advent of ‘app-solute’ chaos in NREGA’, The Hindu, June 25, 2022. https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/the-advent-of-app-solute-chaos-in-nrega/article65561536.ece

- Buddha, Chakradhar and Laavanya Tamang, “From Aadhaar Mandate to Mass Job Card Deletions”, Economic & Political Weekly, Vol. 58, Issue No. 38, 23 Sep, 2023.

- Dreze, Jean and Nikhila Nair, “Mango plantation: A reminder of how NREGA can tremendously contribute to rural development”, Economic Times, 13 March, 2023. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/opinion/et-commentary/mango-plantation-a-reminder-of-how-nrega-can-tremendously-contribute-to-rural-development/articleshow/98613894.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

- Gupta, Apurva and Laavanya Tamang, “Runup to Interim Budget 2024: The minimum NREGA budget for FY 2024-25 must be Rs 2.71 lakh crore”, Down to Earth, January 31, 2024.

- Johari, Aarefa, 2018. “A year after Jharkhand girl died of starvation, Aadhaar tragedies are on the rise”, scroll, September 28, 2018.

- Lalwani, Vijaita, 2022.”NREGA Workers Are Losing Wages Because Of Mandatory App Attendance”, Article 14. July 5, 2022. https://www.article-14.com/post/nrega-workers-are-losing-wages-because-of-mandatory-app-attendance–62c39de7b5d3d/

- LibTech India, 2020. “Length of the last mile”, http://libtech.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/LastMile_ReportLayout_vfinal.pdf

- Nair, Sobhana, 2023. “Job card-Aadhaar mismatch | A missing letter means no work for MGNREGS workers in Odisha”, The Hindu, June 24, 2023, https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/job-card-aadhaar-mismatch-a-missing-letter-means-no-work-for-mgnregs-workers-in-odisha/article67005710.ece

- Narayanan, R., Dhorajiwala, S., and Golani, R. 2019. “Analysis of Payment Delays and Delay Compensation in MGNREGA: Findings Across Ten States for Financial Year 2016–2017,” Indian Journal of Labour Economics (62:1), pp. 113–133. (https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-019-00164-x).

- Tapasya, 2022. “Millions Of Children Will Soon Need Aadhaar IDs To Access Their Right To A Nutritious Meal”, Article 14, 30 June, 2022. https://article-14.com/post/millions-of-children-will-soon-need-aadhaar-ids-to-access-their-right-to-a-nutritious-meal–62bc915131cc9

- Upasak Das, Amartya Paul, Mohit Sharma, Reducing Delay in Payments in Welfare Programs: Experimental Evidence from an Information Dissemination Intervention, The World Bank Economic Review, Volume 37, Issue 3, August 2023, Pages 494–517, https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhad011

![Digitalisation in India: The Class Agenda [Part IV]](https://rupe-india.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/aspects-84-part-4-feature-1080x675.jpg)

![Digitalisation in India: The Class Agenda [Part III]](https://rupe-india.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/from-the-website-of-the-Department-of-Food-and-Public-Distribution.png)

![Digitalisation in India: The Class Agenda [Part II]](https://rupe-india.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/11.-Dharavi-metal-worker-3494547407_17a7cc1830_o-e1715785805276-1080x655.jpg)

![Digitalisation in India: The Class Agenda [Part 1]](https://rupe-india.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/81-82-digitalisation-class-agenda-1080x653.jpg)