Part 1

India, according to its rulers, is not only a global power, but a Vishwaguru (Global Teacher). This claim may not be borne out by the level of Indians’ per capita income, productive employment, farm output per hectare, manufacturing strength, technological base, educational status, nutrition, and health. Nor do the distorted structure of India’s employment, the abysmal economic status of its women, and its overall lack of political and social freedoms support the claims of Global Teacher status.

Nevertheless, in one sphere India’s achievement has won global recognition: its high-speed drive for digitalisation. In the view of the American billionaire Bill Gates, “No country has built a more comprehensive [digital] platform than India.” The Indian billionaire Nandan Nilekani, the most prominent evangelist for digitalisation in India, claims that “India is upgrading – from an offline, cash, informal, low productivity economy to an online, cashless, formal, high productivity economy.”

Such claims are bolstered by international institutions such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF). According to the World Bank’s World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends,

Technology can be transformational. A digital identification system such as India’s Aadhaar, by overcoming complex information problems, helps willing governments to promote the inclusion of disadvantaged groups…. a digital ID, by giving millions of poor people an official identity, increases their access to a host of public and private services.

Indeed, a widely-cited IMF study of March 2023, Stacking up the Benefits: Lessons from India’s Digital Journey, treats India as a development model: “India has developed a world-class digital public infrastructure (DPI) to support its sustainable development goals…. India’s journey highlights lessons for other countries embarking on their own digital transformation.” Although the study is short on actual evidence for the benefits of India’s digitalisation, it is useful as a summary statement of the claims themselves.

According to the IMF study, India’s ‘digital public infrastructure’ (composed of digital identity, principally Aadhaar; digital payments systems, principally Unified Payments Interface, or UPI; and data exchange, such as DigiLocker) has enabled a range of positive effects. These include:

— increasing the efficiency of Government transfers to the poor;

— lowering the costs of public programmes;

— increasing Government revenues;

— reducing corruption and errors of inclusion and exclusion in Government programmes;

— accelerating the formalisation of the economy;

— improving the transparency and accountability of Government;

— improving ‘financial inclusion’ and the penetration of financial services;

— improving the selection of borrowers/insured persons;

— enabling new digital businesses;

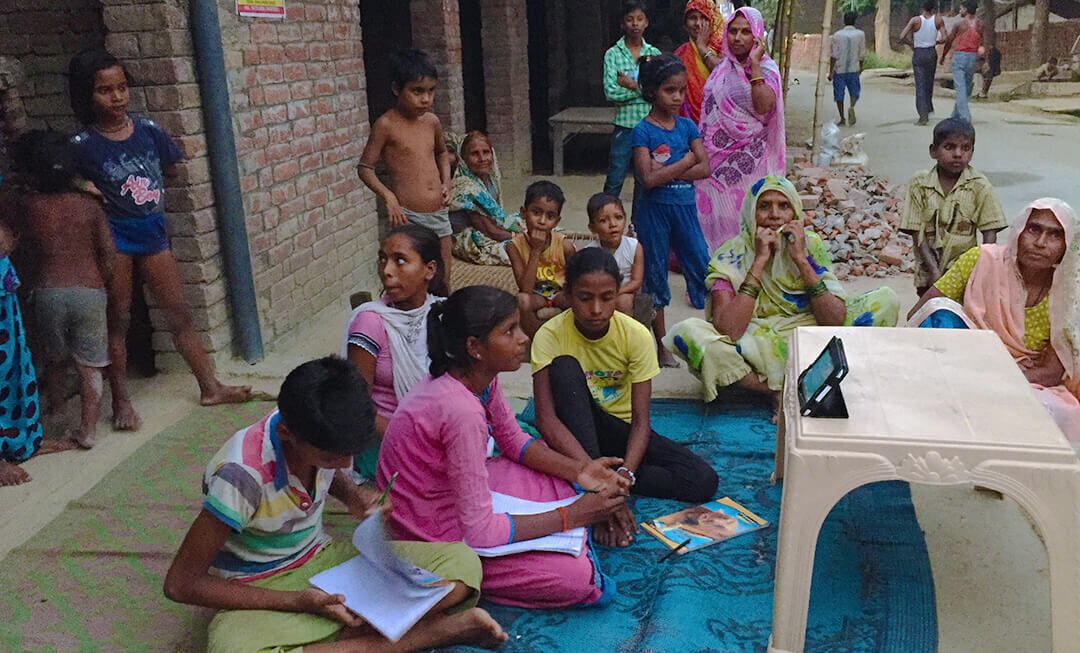

— making public and private services in health and education more convenient, speedy and efficient;

— enabling more convenient payments systems that benefit both consumers and firms, including micro, small and medium enterprises (especially smaller merchants); and so on. The study projects that “Further progress in digitalization could improve India’s productivity in the medium and long term, lifting potential growth above pre-pandemic levels….”

In the following note, we look at the impact of digitalisation on the economy as a whole, as well as on specific sectors. We place it in the specific context of India’s economy and society, and argue that the manner in which it is being carried out serves a specific class agenda.

Digitisation vs digitalisation

The terms ‘digitisation’ and ‘digitalisation’ are used interchangeably by many people; others draw distinctions between the two, some adding a third term, ‘digital transformation’; but there does not appear to be a standard usage. We adopt the following usage:

‘Digitisation’ refers to “the process of converting information into a digital (i.e. computer-readable) format.” For example, scanning a set of family photos converts them into digital format (encoding them using the digits 0 and 1.)

‘Digitalisation’ refers to the use made of digitised data and digital technologies for various social and economic processes. In the case of a business enterprise, examples of ‘digitalisation’ may include digital marketing; receiving payments through digital channels; analysing data generated throughout the business organisation, and on this basis reorganising the business process; changing the business model itself to provide services from the ‘cloud’; and so on. In the case of the State, it may include creating digital records and identities; providing information to the public through the internet, and channels for the public to interact with the State machinery; providing services such as education and healthcare through digital channels; using digital technology to improve the efficiency and monitoring of various services; shifting the filing of returns and administration of taxes to the digital mode; making digital payments of wages and welfare transfers; and so on.

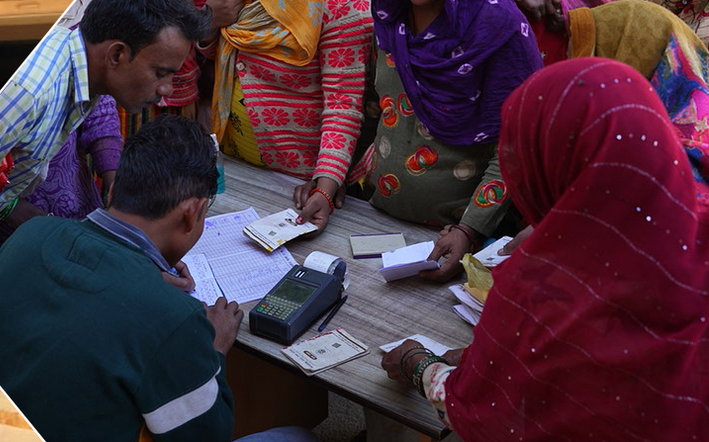

Thus, an individual may digitise his/her own photograph, iris scan, fingerprints, address, date of birth, and parent’s name; however, when the State does these actions, and on that basis creates a digital identity (such as Aadhaar), that is an act of digitalisation. Once created, this digital identity may acquire extraordinary significance, even overpowering the person it claims to identify; thus the failure of a person’s fingers to match the Aadhaar fingerprints routinely leads to the denial of rations, wages, welfare payments, and so on. The Aadhaar is real, the person in question may be treated as fake.

Rapid advance of digitalisation

Undoubtedly, digitalisation has advanced in India at a rapid pace in the last 10 years, which we will refer to as the period of ‘peak digitalisation’. This can be seen in the growth of digital payments, the emergence of new firms based on digitalisation, and the shifting of transactions between the Government and citizens to the digital mode. To take a few examples:

— Digital retail payments have grown between 2016-17 and 2022-23 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 51 per cent and 27 per cent in volume and value terms. India’s digital consumer base is said to be the second largest in the world, and growing at the third fastest rate amongst major economies. In the period since the Covid-19 pandemic, credit and debit cards in circulation crossed the 1 billion mark. Transactions using the Government’s RuPay card grew at a CAGR of approximately 40 per cent between 2016-17 to 2021-22. As can be seen from Chart 1, in the last five years the volume of transactions has been growing faster than the value, indicating that digital modes are being increasingly used for small payments.

Note: Includes payments by all digital modes, including ABPS, IMPS, NACH, NEFT, UPI, debit transfers, card payments, PPI, etc.

Source: RBI Database, Payment Systems Indicators.

— The ‘fintech’ industry has captured a sizeable share of the market of non-banking financial corporations (NBFCs), Of the 14,000 newly founded start-ups between 2016 and 2021, close to half belonged to the FinTech industry. An RBI report claims that FinTech lending is poised to exceed traditional bank lending by 2030.

— The Government has shifted its transfers to citizens to the ‘Direct Benefit Transfers’ (DBT) mode. In 2023-24, the Government claimed to have carried out 7.2 billion DBT transactions to transfer Rs 5.9 lakh crore (Rs 5.9 trillion) to various individuals under 314 schemes; of this, Rs 2.6 lakh crore was in cash, and Rs 3.3 lakh crore in kind (principally rations, fertiliser, and cooking gas).

Chart 2: Direct Benefit Transfers, in Cash & Kind

— In turn, citizens engage with, or are compelled to engage with, the Government through digital channels. As of July 31, 2023, nearly 1.37 billion Aadhaar numbers had been generated, and Aadhaar had been used for almost 103 billion authentications. The Goods and Services Tax Network (GSTN), launched in 2017, records invoice level data from every GST-registered business in the country, on the basis of which input tax credits are calculated. Between GSTN’s start in July 2017 and end-March 2022, newly registered GST taxpayers (i.e., apart from those already registered under the earlier indirect tax regime) rose to 8.8 million.

Digital infrastructure

The Government of India’s creation and ownership of the ‘India Stack’ serves as digital infrastructure for this digitalisation drive. The India Stack consists of three layers: establishing identity (Aadhaar), payments systems (Unified Payments Interface, Aadhaar Payments Bridge, Aadhaar Enabled Payment Service), and data exchange (DigiLocker and Account Aggregator). This infrastructure required large State investments (the costs of the Aadhaar programme alone have been estimated at $10-12 billion), but steeply lowered the costs for digitalised businesses to authenticate and acquire customers and receive payments. The use of Aadhaar, according to Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, has brought down the cost of customer acquisition from Rs 500-700 ($6-9) per person to Rs 3 (0.4 cents).

Several steps taken by the Indian government in recent years were key to this process. In January 2009, the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government set up the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), appointing Nandan Nilekani as the chairman. The UIDAI began collecting the biometrics and demographic data of residents of India and allotting each such person a 12-digit unique identity number, the Aadhaar, and the UPA government began using it for verification purposes of banks, telecom companies and government departments; in 2012 it launched a Direct Benefits Transfer scheme. “We felt speed was strategic. Doing and scaling things quickly was critical. If you move very quickly it doesn’t give opposition the time to consolidate,” said Nilekani. As yet the entire Aadhaar project had no legislative backing. In 2013 the Supreme Court ruled that the scheme was voluntary, and the Government could not deny a service to anyone who did not possess an Aadhaar.

Although the BJP campaigned against the Aadhaar before it came to power, the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance government quickly embraced the project. Following a July1, 2014 meeting between Nilekani, the Prime Minister and the Finance Minister, the new government re-launched the Aadhaar drive with redoubled energy, providing it legislative backing. Moreover, in August 2014, the Prime Minister launched the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana, under which more than 520 million no-frills, low-cost bank accounts have been opened to date, almost exclusively by public sector banks.

These two measures, combined with the spread of mobile telephony, enabled what the Economic Survey 2014-15 called the “JAM Number Trinity” – Jan Dhan Yojana, Aadhaar and Mobile numbers, a coinage of the then Chief Economic Advisor (CEA), Arvind Subramanian. The Survey claimed that subsidies were not a good way to fight poverty; among other things, it argued that subsidies distorted prices, resulting in an inefficient allocation of resources in the economy. It proposed eliminating or phasing down subsidies on food, energy, fertiliser, rail travel, and other goods/services, and replacing them with targeted transfers to a narrowly defined category of the ‘poor’:

If the JAM Number Trinity can be seamlessly linked, and all subsidies rolled into one or a few monthly transfers, real progress in terms of direct income support to the poor may finally be possible. The heady prospect for the Indian economy is that, with strong investments in state capacity, that Nirvana today seems within reach. It will be a Nirvana for two reasons: the poor will be protected and provided for; and many prices in India will be liberated to perform their role of efficiently allocating resources in the economy and boosting long run growth.

Indeed, the celebration of the magical powers of digitalisation is closely linked to neoliberal economic theory.

Digitalisation and neoliberal economic theory

Keynesian economic theory, dominant in western capitalist countries from the end of World War II to the 1970s, held that the level of economic activity is basically determined by the level of aggregate demand. Unlike Marxists, Keynesians did not view the periodic crises of capitalism as manifestations of an irreconcilable social contradiction. But they also did not believe the ‘free market’ would spontaneously and continuously ensure full employment. They acknowledged that capitalist economies tended to suffer periodic slumps in demand, during which private capitalists failed to invest, workers lost their jobs, and demand consequently spiralled downward. In such circumstances, they argued, the State should intervene in order to stimulate demand through Government spending and reduced interest rates, till private investment kicked in and revived employment.

By contrast, neoliberal economic theory, dominant since the 1980s, considers that, as long as the State, trade unions and the like do not interfere with ‘free’ markets, full employment will automatically materialise. In the world of neoliberal theory, each atomised individual enters into exchange with a universe of other atomised individuals, in a freely competitive process. (For example, each worker individually contracts with the capitalist to sell his/her labour for a wage, and neither party can set the terms.) This theory argues that, in a truly free market, prices automatically adjust in order to ensure full employment of all factors of production (for example, in a free market, wages fall to the point at which capitalists find it profitable to hire workers once more). At times of crisis and collapse of demand, what is needed are ‘structural reforms’ to allow markets to clear – for example, changing labour laws to allow wages to fall, winding up public procurement to force farmers’ sale prices to fall, changing land/environmental laws to bring more land on the market, and so on. All prices are simultaneously determined (by demand and supply), and all markets clear completely, ensuring full use of resources. In the view of neoliberals, this guarantees an optimal outcome in all situations.

Neoliberal theory, taken at face value (i.e., without examining the class interests behind its promotion) is thus a type of magical thinking or religious belief in the free market. For capitalists, it has the attractive feature that, since all outcomes of the market are the best possible in the circumstances, they are all justified.

When agencies such as the IMF, the Indian authorities and pundits like Nilekani promote the notion of a digitally empowered utopia, they are merely embellishing existing neoliberal theory with magical notions regarding technology. One of the weaknesses of neoliberal theory was that it assumed that all participants in the market are equally and perfectly informed; with the revolution in information technology, neoliberal theorists believe that this Nirvana is within reach.

For example, the IMF paper cited earlier says that “DPIs [digital public infrastructures] act as digital building blocks to drive innovation, inclusion, and competition at population scale.” (emphasis added) According to the paper, digitalisation drives the formalisation and transformation of the economy, penetration of financial services, extension of credit to underserved sectors such as micro, small and medium enterprises, more efficient health and education services, and so on. All of these goals were earlier the job of the State, requiring specific measures and budgetary allocations.

After many struggles by India’s peasantry to obtain decent prices for their crops, the Indian government instituted in the 1960s a system of public procurement of foodgrains at minimum support prices. There is a widespread demand among the peasantry for this system to be extended to other crops as well, and intransigent refusal by the Indian State to do so. Neoliberals, by contrast, believe that prices should be “liberated to perform their role of efficiently allocating resources in the economy”. All that is needed is to link all agricultural markets to a national digital platform and thereby provide a “transparent price discovery system”. Moreover, in place of the Government directing a specific percentage of bank credit to agriculture, ‘fintech’ firms can assess the creditworthiness of agricultural borrowers, even the smallest ones, through analysis of transactions data. To minimise any pains of the transition, some minimum income can be provided to peasants through Direct Benefit Transfer.

In earlier times, the Indian working class had fought long struggles to compel the colonial and later the post-colonial Indian State to enact labour laws regulating relations between the capitalist and workers. Although these were enforced for only a minority of workers, they became immediate struggle-demands for other workers as well. However, digital firms such as Uber and Zomato pose as mere platforms through which individual customers and suppliers of services can meet and strike deals, without any labour law or social protection: the epitome of the neoliberal vision of the market.

In brief, the magic of digitalisation is meant to substitute Government intervention with respect to boosting aggregate demand, addressing the basic needs of the people (healthcare, education, credit) as well as the special needs of specific sections, setting up the physical infrastructure and institutions needed for these purposes, sustaining peasant agriculture, and regulating capitalist-worker relations.

Trauma, coercion, and digitalisation

Given this ideology, the digitalisers present digitalisation as a spontaneous, voluntary, people-driven process. A typical article on the subject is replete with clichés such as the following:

India is a very large country of very young people…. India’s population isn’t just young, it is connected…. These young Indians are aspirational and motivated to use every opportunity to better their lives…. It’s about finding innovative solutions to address pressing problems in health care, education, agriculture, and sustainability…. The Aadhaar is a 12-digit unique identity number with an option for users to authenticate themselves digitally—that is, to prove they are who they claim to be…. the data remain under the citizens’ control, further encouraging public trust and utilization.

The fact is, the use of digital payments in India has been pushed by three great traumas to the people: demonetisation, the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax, and the Covid-19 lockdown.

1. The November 8, 2016 decision of the Modi government to invalidate large denomination currency notes (which accounted for 86 per cent of the cash in circulation) dealt the Indian economy, particularly its vast informal sector, a terrible blow. Nilekani saw it as an opportunity: “Demonetisation will help digitisation of the economy and the roll out of digital financial services. What could have taken about six years can now be done in six months.” The IMF paper remarks: “While it was disruptive, demonetization led to greater use of other forms of payment, including the UPI.”

Indeed, less than two months later, the Prime Minister presented demonetisation as a step taken consciously to promote digitalisation: as a result of demonetisation, he declared, cashless transactions had increased by 200-300 per cent.

2. The imposition of GST had an even more severe impact on the informal sector. Heavy compliance costs, the blocking of working capital (since GST payments have to be made whether or not the purchaser’s payment is received), and the loss of market for units without GST-registration wiped out units and employment. A survey-study of small firms found that more than 50 per cent experienced a fall in turnover of 10-30 per cent; another 36 per cent of firms reported a fall of over 30 per cent. More than 50 per cent of the firms retrenched workers after the imposition of GST, with average employment per unit falling 17 per cent.

The IMF paper entirely ignores this catastrophic outcome and merely commends the increase in the number of taxpaying firms as a result of GST. The Economist rejoices in the belief that GST and digitalisation are driving the “formalisation” of the Indian economy, and looks forward to the day when the informal economy’s “sights, sounds and smells may be less pervasive in future”; “Imagine”, it says, “an India without hawkers.”

3. The sudden nationwide lockdown imposed in anticipation of the spread of Covid-19 went even further than the earlier two steps in shutting down the informal sector for an extended period. However, in the words of the RBI think tank CAFRAL, Covid-19 was “An opportunity for FinTechs”: “Consumers and businesses were forced to move online, and digital activity increased globally…. FinTech lenders, already at the forefront of the digital lending revolution, could exploit the inherent advantages of limited manual intervention and face-to-face interactions to cater to a range of consumers.” India’s official investment promotion agency boasted that “Covid-19 has accelerated India’s digital re-set”: “The country was already on a digital-first trajectory with one of the highest volumes of digital transactions in the world when the pandemic struck, and further propelled the use of contactless digital technology.” The Chief Economic Advisor expressed satisfaction that “The pandemic played an instrumental role in accelerating the pace of digitization and that the sectors of education and healthcare are some of the key areas where digital economy will play a key role going forward.”

The adoption of Aadhaar itself has been presented as purely voluntary, indeed, a demand of the people themselves. Bill Gates tells us that “For the last decade, Nandan Nilekani has been working to make these ‘invisible people,’ as he calls them, visible by giving them access to official identification…. there is growing awareness in the global community that with a proof of ID, the world’s poorest people have a powerful tool to be seen, heard, and improve their lives….” Says Nilekani, “Aadhaar e-KYC has been revolutionary in making life simpler for people”.

Had the Aadhaar been adopted voluntarily by people, the Government would not have needed to make it compulsory, in practice, in order to obtain a SIM card, a birth certificate, a death certificate, a bank account, a school midday meal, benefits under any Government scheme, school admission, and so on. As Jean Drèze remarks, “saying that Aadhaar is voluntary is like saying breathing or eating is voluntary.”

In the following section, we turn to the impact of digitalisation on India’s economy.

Footnotes: