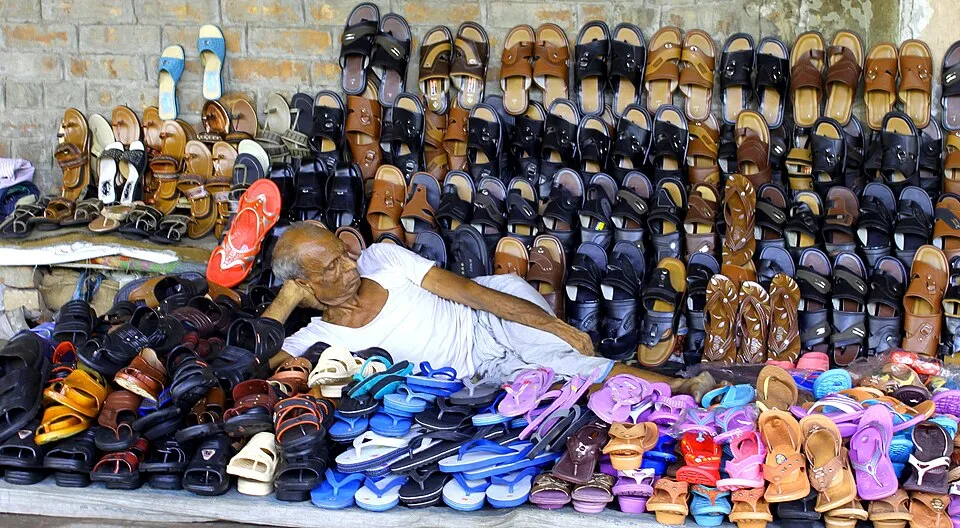

The Depression of Mass Consumption

According to official national income figures, India’s economy is growing rapidly. However, national income, or GDP, is not a directly observed fact, but a construct.... Read more.

Two Faces of the Demand Problem (Part 1)

I. Mountains of Cash India’s large capitalists and India’s people are both facing problems at present. These problems appear to be direct opposites of each other;... Read more.

Two Faces of the Demand Problem (Part 2)

II. Deteriorating Financial Situation of the People Elsewhere in this issue of Aspects, we have described the fall in real incomes of the masses of people in recent... Read more.

Two Faces of the Demand Problem (Part 3)

III. Accumulation amid Distress In the previous two parts we saw that the corporate sector and the banks are sitting on a mountain of cash, and refusing to invest,... Read more.

What Explains India’s Response to Trump?

To a person unfamiliar with India’s history and political economy, the Indian government’s response to Trump’s actions must be puzzling. Consider: Not only... Read more.

The Adani Group and International Capital

The year 2023 was a tumultuous one for the Adani Group of companies. We look here at a limited question: what, if anything, did Adani’s crisis and his recovery... Read more.

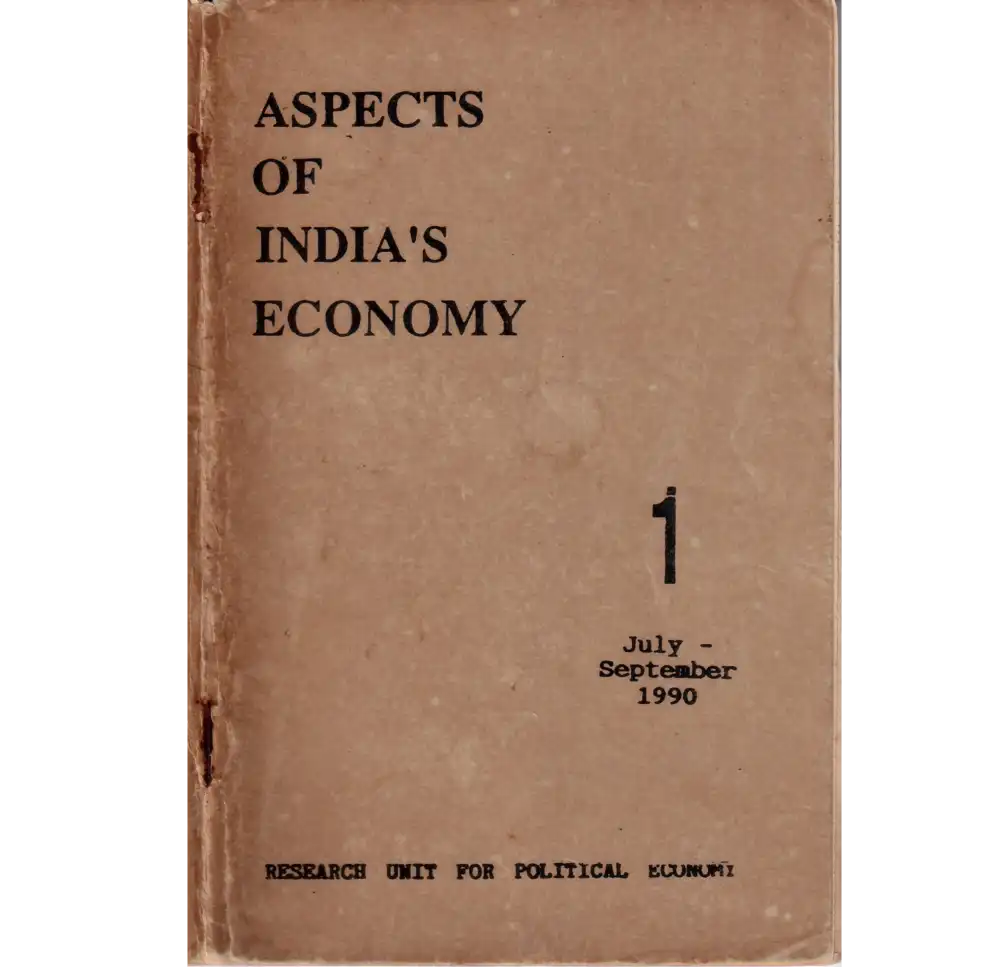

Thirty-Five Years of Aspects

The economy should be the concern of ordinary people. For it is they who work it. And the quality of their lives, their joys and tragedies, are decided by the way... Read more.

Digitalisation in India: The Class Agenda

The champions of digitalisation claim that “India is upgrading – from an offline, cash, informal, low productivity economy to an online, cashless, formal, high... Read more.

The Conditions of India’s Peasantry and the Digitalisation of Agriculture

The Government’s project of digitalising India’s agriculture is premised on a distorted understanding of both private corporations and the mass of India’s... Read more.

Fintech and the Mirage of ‘Financial Inclusion’

The Government and the RBI have been propagating the notion that digital lenders can complete the unfinished agenda of ‘financial inclusion’, and even replace... Read more.