No. 55, March 2014

|

|

|

|

No. 55, March 2014 |

|

|

No. 55 Are There Just Too Many of Us? What the Fall in the Current Account Deficit Reveals

|

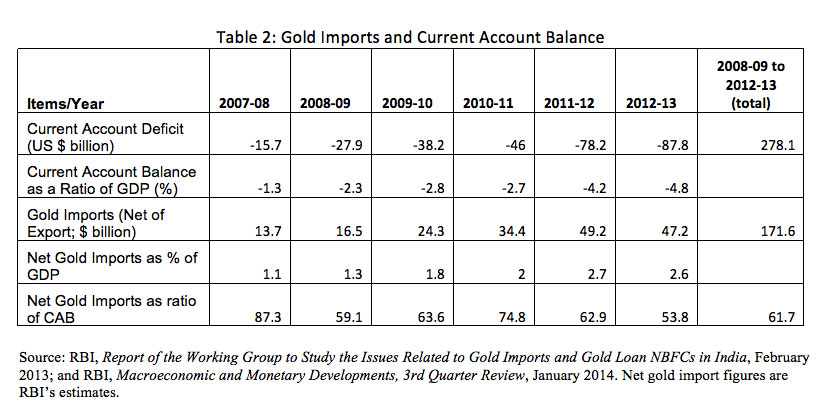

What the Fall in the Current Account Deficit Reveals The Government has released balance of payments data for the third quarter of 2013-14, i.e., October-December 2013 (Q3 2013-14). They show a dramatic improvement in the current account deficit (CAD). As we mentioned in Aspects no. 54, the current account balance is the balance of all current payments to, and receipts from, foreigners. This includes the balance of (i) merchandise trade, (ii) trade in services (e.g. software), (iii) transfers (e.g. workers’ remittances), and (iv) investment income (income on loans and investments made by foreigners to Indians, and vice-versa). In India the current account balance is generally in deficit. That is, our payments are more than our receipts. This gap has to be bridged by either drawing down the foreign exchange reserves, or by capital inflows in the form of loans or foreign investment. The latest data show that the CAD has fallen very sharply, from $31.9 billion in the third quarter of last year (October-December 2012) to just $4.2 billion in the third quarter of this year. The CAD as a percentage of GDP has fallen from 6.5 per cent of GDP in the third quarter of last year to just 0.9 per cent in the third quarter of this year. Turnaround on account of merchandise trade

Trade deficit lower due to fall in gold imports Secondly, and more importantly, gold imports fell by $14.7 billion. That is, 58 per cent of the improvement in the merchandise trade deficit, and 53 per cent of the improvement in the CAD, was on account of gold imports alone. This way of shrinking the trade deficit was painless for the masses of people and for the productive activity of the economy. Gold imports fall due to restrictions Now, precisely such methods are anathema to the neo-liberals who rule the country, both in the finance ministry and at the Reserve Bank. After all, as gold imports were liberalised step by step since 1993, and particularly since 1999, we have been assured that allowing free import of gold was both safe and necessary. Moreover, we were told (by the gold import lobby) that any attempt at restricting gold imports was futile: If gold were not allowed to come in legally, it would be smuggled in. And since smuggled gold has to be paid for somehow by Indians, illicit payments would take place. These illicit payments would be reflected somewhere else in the balance of payments. For example, the price of imports can be overstated by goods importers, or the price of exports can be understated by goods exporters; accordingly, either more dollars are paid out, or less dollars come in, and the difference is used to pay abroad for the smuggled gold. Alternatively, Indian workers abroad may remit less money home, and those funds would find their way to pay for smuggled gold. And so, the gold import lobby said, any attempt to curb the CAD by restricting gold imports would fail: legal gold imports might fall, but illegal (smuggled) imports would be reflected in either a rise in the trade deficit or a fall in remittances, and in the end the CAD would be as high. Let us leave aside the fact that this theory depends on the Government’s complete inability to check smuggling – so complete that it amounts to lack of political will, or collusion. The fact is that the liberalisation of gold imports greatly increased the market for gold. Moreover, in the period after 2008, when the stock market slumped and real estate prices stagnated, private investors were looking for a place to park their money and get high returns, and gold was at the time still giving such returns. It was this investment demand for gold, more than the ‘marriage’ demand, that drove imports. This demand could not have grown so fast without a large legal trade in gold.

The burden of the gold binge Despite this, there has been a stream of articles in the business press, fed by the World Gold Council (WGC), claiming that gold smuggling has grown hugely, and that the gold import restrictions are counter-productive. Why is the WGC worried about what it claims to be an increase in the smuggling of gold into India? It is, after all, an organisation of gold mining firms. Whether gold is brought into India legally or smuggled in, the members of the WGC make their money. Now, the WGC claims that the smuggling of gold into India has risen so sharply that, despite the sharp fall in legal imports, total gold imports (legal + illegal) have risen. If the WGC’s claims are true, it is a mystery why they should be agitating for India to remove the restrictions it recently placed on gold imports. The truth is, they want the restrictions removed because they want to revive demand back to the levels of the binge of the earlier period. From the point of view of conservation of foreign exchange, it does not matter much whether gold is brought in legally or smuggled in. Either way, as we discussed above, there is a drain of foreign exchange. Whichever method results in lower total imports (legal + illegal) should be adopted. As we have seen, even mild import curbs have resulted in lower imports; sterner curbs, combined with beefed up measures to check smuggling, would yield even better results. The problem is the powerful interests in India ranged against any such measure. For the moment, because of the gravity of the external crisis, the Government is unable to oblige them. But it has given ample signals that it will relax the import curbs as soon as possible, to ensure a revived flow of this barren commodity so beloved of wealth holders. Sonia Gandhi has asked for a reduction in tariffs and a relaxation of the export obligations.4 The RBI Governor has clearly opined that, while it is not immediately possible to remove the curbs, they should be done away with as soon as possible; inevitably, he has warned that smuggling would increase if the import curbs stay.5Official theories have pat explanations for trade deficits, such as ‘uncompetitive manufacturing’ (i.e., high wages), generalised ‘excess demand’, ‘inadequate domestic savings.’ Evidently, however, the problem lies elsewhere. There are powerful class forces in the political economy of the country that sustain persistent current account deficits. We have highlighted gold imports because they strikingly illustrate how the policy of liberalisation clashes with national interests, how the mechanisms by which trade deficits are supposed to correct themselves do not work, and why scarce foreign exchange must be rationed in line with national needs. This logic, of course, applies not only to gold, but to a host of other imports – a large share of consumer goods, capital goods, intermediates, and even fuel, all of which have contributed to unnecessary imports. All the more reason for the powerful interests which promote external liberalisation in general to oppose the extension of curbs on gold imports.

Notes: 1 There was no doubt also a slight pick-up in software exports, on the back of a slight recovery in the US economy. (back) 2. Three restrictions were imposed in the course of 2013: (i) Import tariff on gold bullion was raised to 10 per cent. (ii) Import of gold on credit or on ‘consignment basis’ (i.e., payment to be made after sale of stocks) was banned. (iii) In August 2013, gold-importing agencies were allowed to make imports on the condition that 20 per cent of the imported gold would be re-exported (after value addition). Permission to import the next lot would be given only on providing proof of having fulfilled this export obligation. (back) 3. In fact, in this quarter, Indians abroad shifted some of the money they would normally transfer home into Foreign Currency Non-Resident deposits instead, since the RBI had made it much more attractive to depositors. Despite this, the figure of private transfers did not fall. (back) 4. See http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2014-01-23/news/46514270_1_import-duty-import-curbs-gold-imports. (back) 5. See http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2013-12-18/news/45338310_1_gold-imports-current-account-deficit-cad and http://www.livemint.com/Politics/tZ87MEMrqWiTIUIu0b8hhM/Raghuram-Rajan-No-doubt-gold-smuggling-will-rise-if-import.html. (back)

|

|

| Home| About Us | Current Issue | Back Issues | Contact Us | |

|

|

All material © copyright 2015 by Research Unit for Political Economy |

|