In the first part of this article, we observed that, at present, the dominant theoretical framework for understanding the economy is that of competitive markets. The economics profession does acknowledge gaps between these idealised markets and reality, but only as imperfections to be taken account of by making certain adjustments, without questioning the framework itself. Accordingly, India’s peasantry too are seen as profit-maximisers, on the lines of competitive firms. Their decisions on the use of different resources – land, labour, inputs – are supposedly guided by these considerations.

The present ideological framing of ‘digitalisation’ thus conceives of the economy as a set of atomised individuals interacting through the free market. Digitalisation claims to remove certain market imperfections faced by ‘the farmer’ (a term covering very different operators, from landlords to middle peasants to very small peasants, including tenants1). With digitalisation, we are told, each farmer will be able to obtain technical and market-related advice tailored to his/her specific needs (what to produce, in what quantities, using what methods); adequate and timely credit tailored to individual risk profiles; information on the prices of inputs; and prices of output across different markets, so as to obtain the best price. Moreover, the digitalisation of land records will reduce land disputes and improve their access to credit.

However, it was demonstrated 50 years ago that the framework of competitive markets is of little use for understanding India’s agrarian sector,2 and this continues to be true despite the greatly increased commercial penetration of agriculture in the subsequent period. As pointed out at that time, if all the costs of cultivators are taken into account, including the imputed cost of family labour and the imputed cost of owned land, many peasants would appear to be making a ‘loss’. Once we assume that all markets are perfect and fully ‘clearing’ (i.e., the supply of all goods, including labour power, exactly equals demand, without unabsorbed supply or unmet demand3), it would seem that these deficit peasants could obtain wage work elsewhere, lease out their land and thereby earn more than they do by cultivating their land themselves.

Contrary to the dominant theory, the markets for land, labour, capital do not ‘clear’ simultaneously or fully. One instance of this is that there are insufficient jobs to draw under-employed peasants out of agriculture, and so they are compelled to remain there even in conditions of acute distress. Evidently, the calculus of cultivators’ production decisions is different from the one assumed by dominant economic theory. The competitive markets framework thus proves of little help in explaining their actual choices. In fact, we need to take account of the gamut of social relations prevailing in order to understand the situation of the peasantry and its choices.

In the following we briefly sketch the conditions in India’s agriculture and those who work it. The relevance of this sketch of agrarian conditions will become evident when we proceed to look at digitalisation and what it claims to do.

I. The Context of India’s Agriculture

1. Very small peasants make up large majority of cultivators

The story of India’s agriculture should be seen as the story of India’s peasantry and the conditions of its labour.

First, India’s agriculture is clearly very different from agriculture in the developed world, where low single-digit percentages of the workforce cultivate giant mechanised farms. The US, for example, has 125 million hectares of harvested cropland, but just 2.1 million farms, with most of the land in holdings of over 200 hectares.4

By contrast, the most striking fact about India’s agriculture is the vast numbers of people involved. Agriculture, forestry and fishing continue to be the single largest sector of employment, accounting for 45 per cent of total employment – nearly 247 million workers. The average size of holding is just 1.08 hectares; each holding in turn can consist of a number of parcels, i.e., non-contiguous plots of land.5 Of the nearly 147 million holdings, 100 million were ‘marginal’ holdings, of less than 1 hectare. Another 26 million were between 1 and 2 hectares. The two categories together thus accounted for more than 86 per cent of holdings.

‘Agricultural households’, with income from self-employment in farming of land or animals, make up 93 million, or a little more than half of all rural households.6 (This does not include landless agricultural labour.) The large majority of cultivators are very small peasants, whose holdings are often termed ‘uneconomic’, i.e., they do not yield enough for their subsistence. Hence they stitch together a subsistence from a number of occupations, including wage work and sundry forms of self-employment outside agriculture. This has even led some scholars to classify all farmers whose agricultural income does not cross 50 per cent of their income as not being “serious farmers”.7

2. Conditions of the vast majority of farmers

This last category of small peasants, whether or not deemed “serious” by scholars, are indeed the vast majority of India’s farmers, and the poorest. There is inadequate employment for them outside agriculture, and hence the income and other forms of sustenance they obtain from agriculture are essential to their subsistence. Recent data tell us that agriculture’s share in total employment has actually risen (from less than 43 per cent in 2019 to over 45 per cent in 2022, representing an addition of nearly 56 million workers8). This is a stark sign of desperation, resulting from the disappearance of other employment. At the same time, it also underlines the importance of the agricultural holding as a bedrock of bare subsistence in a working life of enormous insecurity.

For farmers with less than 1 hectare of land, income from all sources (agricultural and non-agricultural) in 2012-13 did not suffice to meet consumption expenditure. They may be chronically deficit households. For farmers one step up, with 1-2 hectares, income from agriculture alone (cultivation + livestock) did not suffice to meet consumption expenditure; they narrowly managed to get by with the help of non-agricultural income, such as wages9 or small businesses.

Between 2012-13 and 2018-19, average household income from crop cultivation fell nearly 9 per cent in real terms. Even if we combine income from crop cultivation and farming of animals, there is a fall in real terms.10 Plainly, agriculture on its own is not yielding a living for the majority of cultivators; and yet they continue to work it.

This may be explained by the very different objectives of different classes of farmers: Depending on their specific conditions, the aim of one set of farmers may indeed be to maximise profits; but another set may be governed by the need to raise subsistence; a third set may be under pressure to produce the largest possible output, irrespective of the profit net of all inputs: “very small farmers may ‘choose’ to raise as much gross value of output as possible per acre, even at the cost of having to incur debts to provide circulating capital; they may be found operating land intensively even to a point where the additional input costs exceed the value of additional output.”11 This is part of the phenomenon of ‘forced commercialisation’.

Given the very different market relations of different segments of the peasantry, the blanket treatment of all peasants as profit maximisers is wrong and misleading.

Indebtedness and environmental crisis as expressions of peasant distress

In these circumstances, peasant indebtedness has emerged as a burning question. Despite under-reporting by survey respondents, half of agricultural households report being in debt, with an average debt of over Rs 74,000 – i.e., 7.25 times the average monthly income of these households. The smaller the size of land possessed by the household, the larger is the share it owes to ‘non-institutional’ sources (moneylenders, traders, commission agents, family and friends), which are generally at much higher interest rates. Moreover, microfinance institutions, which are listed by official surveys among ‘institutional sources’, charge interest rates comparable to those of moneylenders. And now, similar rates are charged by digital lenders.

A striking expression of the crisis of peasant debt has been the phenomenon of peasant suicides: between 1995 and 2019 , nearly 3.65 lakh peasants are reported to have committed suicide, at the rate of nearly 14,600 a year; even this appears to be a serious underestimate.12 The link to indebtedness is evident: for example, a recent study found that debt-related suicides accounted for 88 per cent of farmer suicides in Punjab during 2000-18.13 The need to service debt may also dictate the crops grown by a peasant. Indebtedness appears to be most acute, and suicides most common, among farmers who grow crops for the market. These farmers may be compelled to produce cash crops in order to be able to repay loans they have taken for cultivation; however, this leaves them particularly vulnerable in the face of fluctuations of the weather, pests and output prices.

As the public sector role in agriculture has been withdrawn, the private corporate sector has penetrated and captured parts of the supply chain. Bayer-Monsanto, ChemChina-Syngenta, DOW-Dupont and BASF control 70 per cent of commercial seed supply, as well as a large proportion of agrochemicals in the country.14 Global agribusiness giants, as well as large Indian corporations such as Adani and ITC, have entered the procurement and trade of agricultural produce.

The crisis of the peasantry and the increasing penetration of the corporate sector have intensified the environmental crisis. The State of Agrarian and Rural India Report 2020 (SARI Report), by a group of scholars of India’s agrarian conditions, brings out the gravity of this crisis. Among other things, it points to the following:

— the large-scale degradation of land (38 per cent of the geographical area is considered degraded);

— the diversion of farmland to real estate and other non-agricultural uses (leading to a decrease in net sown area by 3 million hectares 1990-2015);

— the extreme imbalance in the principal soil nutrients (nitrogen, phosphate and potassium), due to the Government’s skewed subsidy policy;

— the falling trend in grain output per kilogram of NPK fertiliser;

— the loss of seed varieties and biodiversity; the increasing frequency and virulence of pest attacks;

— the decline of the water table with the over-extraction of groundwater; the pollution of rivers; and

— the threat of total collapse of ecosystems with pollinators and insects disappearing due to use of agrochemicals.

Forests are part of the agrarian sphere, with forest dwellers subsisting on a combination of cultivation of crops and collection of forest produce. The degradation of forest and mountain systems due to mining, and the destruction of dense forests, are destructive of these forest dwellers’ agrarian livelihoods as well. These trends have assumed grave proportions.

Given the stress it faces in trying to make ends meet and service mounting debts, the peasantry is driven to various short-term ‘fixes’, however unsustainable; for it is not in a situation to adopt longer-term solutions. Thus peasants are driven:

— to extract groundwater and drive the water table lower;

— to use an excess of nitrogenous fertiliser, which is as yet price-controlled, to make up for their under-use of high-priced phosphate and potash;

— to abandon known, traditional methods of renewing the soil, fertilising it and controlling pests, because such methods may increase their labour costs as well as temporarily curb their gross revenues;

— to stick to growing certain input-intensive crops such as rice, wheat, cotton, and sugarcane because they yield higher gross cash revenues;

— in some regions, to burn residue from one crop to quickly prepare the ground for the next crop; and so on – the examples can be multiplied. Peasants are aware of the harmfulness of all these practices, but individually they cannot avoid them.

Peasants’ insistence on free electricity and write-offs of bank debt are expressions of this crisis. The demand for a guarantee of remunerative crop prices may seem anomalous – after all, there is no guarantee of a living wage for workers. However, it is a justified demand for peasants, for whom there is no escape from their present situation – as starkly demonstrated by their suicides. (At the same time, we should note that demands for higher crop prices, free electricity and loan write-offs also suit powerful landed interests; hence they are frequently conceded to one extent or the other by the rulers.)

The costs of production for the small peasant are higher than for large land holders. As mentioned above, a larger share of small peasants’ loans is from ‘non-institutional’ sources, at higher interest rates. They pay higher prices for fertiliser.15 They have less access to water from irrigation projects, and less access to groundwater, as the deeper tube wells tend to be owned by larger farmers.16 Costs of hiring machines, seed costs, and rent on leased-in land are consistently higher for smaller farmer households than for large farmers.17

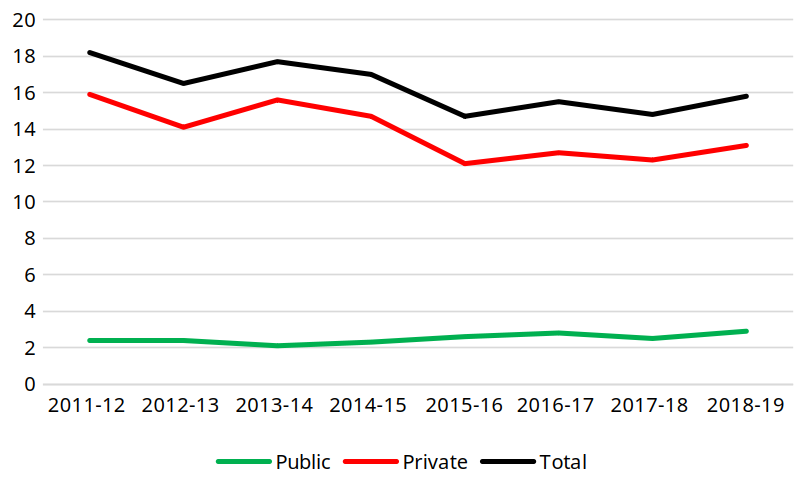

Given the difficulty in meeting even consumption expenditure from agriculture, farm households are unable to invest in increasing productivity: the average annual expenditure on productive assets was just Rs 2,652 per agricultural household in 2018-19.18 While public investment in agriculture has stagnated at low levels, private investment has been declining over the last decade (see Chart 1).

Chart 1: Investment in Agriculture as % of Gross Value Added in Agriculture: Public, Private and Total

3. Those excluded from land, or from land records

Tenant farmers

Informal tenancy is still significant in India, though its incidence and nature vary from region to region. Small and marginal farmers still constitute the majority of lessee households: a recent study based on National Sample Survey data finds that “most tenancy contracts in India are either between large landowning lessors and poor tenants, or lateral tenancy contracts, in which land is leased out by a household to another with a similar socio-economic status.”19 The study finds that ‘reverse tenancy’, i.e., leasing by small farmers to large farmers, is still not significant.

Most tenancies are oral, to evade the protections provided to tenants under tenancy laws. Thus recorded tenancies are negligible, the figures from Government surveys are low, but independent micro-surveys find much higher figures. For example, tenant farmers are estimated to account for 65-80 per cent of the paddy crop in coastal areas of Andhra Pradesh;20 and the head of the Bihar Land Reforms Commission of 2006-08 claimed that one-third of the land in Bihar was under sharecropping, and one third under tenancy; only the remaining third was cultivated by independent peasant farmers.21 Government surveys find the prevalence of tenancy to be rising considerably in the last two decades.22 Insecurity of tenant tenure is particularly high in eastern and central India (Bihar, Eastern Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Chattisgarh, Jharkhand and Odisha).23

Apart from tenant farmers, certain other sections of cultivators too do not find a place in discussions regarding ‘farmers’: namely, Dalit farmers, Adivasi farmers, and women farmers. In the context of the ‘digitalisation’ of agriculture, they face specific problems.

Landlessness and caste

Digitalisation functions on the basis of the existing distribution of assets; it cannot address problems which are due to the extreme inequality in that distribution. While 80 per cent of Dalits live in the rural areas, 58 per cent of rural Dalits are landless; the figure rises to more than 85 per cent in Haryana, Punjab and Bihar.24 Moreover, the size of Dalit holdings is a fraction of those of other communities – in some states as low as one-twentieth.25 The Dalits have meagre access even to the market for leasing-in of land.26 An essential element of emancipation of Dalits from their social oppression is a radical change in the existing highly unequal land relations.

Forest-dwellers

Many farmers who possess land may not enjoy legal title to it, for social and historical reasons. This is especially true of Adivasis, 92 per cent of whom live in the rural areas, and are the most dependent on agriculture of all communities. Despite the Forest Rights Act (FRA) of 2006, their holdings remain highly insecure. By October 2023, 17 years after the enactment of the FRA, 4.4 million claims had been filed for individual forest rights, but only about 2.2 million titles had been distributed – for an area of 1.94 million hectares, or about 0.87 hectares per claim. Community forest rights (CFRs) include various rights essential to the subsistence of forest-dwelling communities, such as rights to forest produce, grazing lands, water bodies, land for habitat, and other traditional rights. Of around 0.19 million CFR claims, titles were distributed in 0.11 million cases, for an area of 5.4 million hectares.27 This should be compared with a conservative estimate of at least 40 million hectares of forest lands eligible for CFR rights recognition across the country;28 thus titles have not been given for over 86 per cent of the CFR area.

Women

Agriculture is the main sector of employment for women: About two-thirds of women considered to be in employment are employed in agriculture – 24 per cent as cultivators and 41 per cent as agricultural labourers. By 2003, women already accounted for 40 per cent of farmers, and were the majority in forestry and animal husbandry. However, women largely lack titles to land. The SARI Report points out that women are not counted as ‘farmers’ by Government data collection sources, since most women (86.5 per cent) do not have land titles in their names. “In the absence of formal recognition, these women ‘cultivators’ are excluded from most government programs such as eligibility for loans of various kinds, thereby, putting them into situations of vulnerability and insecurity on an everyday basis.”29

The livestock sector accounted for 28 per cent of agricultural GDP in 2018-19, and it is growing nearly four times as fast as the crop farming sector. Around 70 per cent of the labour in the livestock sector is by women. A recent study shows how the livestock-related labour of women may be rendered invisible in official statistics:

A time use survey in a village of Karnataka showed that a poor peasant woman started her day by collecting dung from the cow shed for 10 minutes (5.15 a.m. to 5.25 a.m.). She engaged in some preparatory cooking tasks for a while. A little later she milked the cow for 25 minutes, and swept and washed the shed for around 30 minutes. After completing other household tasks, she went to work on a construction site. She took two cows along and tied them to graze near the work site. When she returned home in the evening, she again milked the animals and fed them, which took around 40 minutes. After dinner, she fed the animals for the last time in the day. This woman spent around 3.5 hours on livestock-related tasks, which were all combined with household duties. Given this pattern of work, the woman herself may not report “livestock raising” as an economic activity.30

While conventional measures put the number of women livestock farmers at 12 million, the above study put the number at 49 million, using a more appropriate measure. This is a large share of the rural population. However, public agricultural extension services (including veterinary services) for the livestock sector are scarce, and within that, they largely ignore women, who contribute the bulk of the labour. Lacking land titles, women also find it difficult to obtain loans to purchase livestock.

Thus digitalisation, based on the existing distribution of land and on the existing land records, may reinforce the disentitlement of vast sections of the peasantry, prominently tenant peasants, landless peasants (particularly of oppressed castes), forest-dwelling peasants (particularly Adivasis), and women peasants.

4. Lack of awareness and access

There is a vast need for agricultural extension services in India that are scientific and appropriate to the environmental, social and economic conditions of small and marginal peasants. Conditions vary vastly from region to region, and extension services need to be tailored to specific conditions – for example, in hilly areas; in regions of dryland farming; in regions of degraded land; and so on. A study by agricultural extension scientists notes:

Apart from landholding size, issues of inclusiveness also arise with respect to disadvantaged regions, crops and marginalised sections of society. This is particularly so in the cases of non-timber forest produce in tribal areas, small ruminants in case of livestock (sheep and goat) and dry land crops. In remote and disadvantaged areas, contact [between] extension agents and farmers is less.31

However, the National Sample Survey on agricultural households shows that more than half of all agricultural households do not avail of any technical advice. Those that do so avail of do so mainly from other households (23 per cent) and input dealers (20 per cent), and fewer from the media (radio, print, electronic). Indeed very small percentages receive advice from the public sector extension network (just 3 per cent from public extension agents). (See Table 1 in Appendix 3.)

This is in line with the Government policy of starving public sector agricultural extension services of funds. Public expenditure on agricultural research and education is just 0.5 per cent of the Gross Development Product in Agriculture (GDPA); public expenditure on extension services is even lower, at only 0.2 per cent of GDPA.32 As a result, there is only one public extension worker for about 1,000 cultivators.33 Due to the Government policy of trying to reduce staffing levels, the number of sanctioned posts of public extension workers remains frozen at 1.4 lakh, of which 30 per cent remain unfilled on the average.34 It is estimated that public extension services reach less than 7 per cent of farmers.35

By contrast, there are 2.8 lakh private input dealers,36 i.e., twice as many as the sanctioned posts of public extension workers. They provide a different type of agriculture extension service: “A major complaint against input dealers is that they indulge in ‘product advisory’ instead of ‘technical advice’ which is brand agnostic…. Aggressive marketing strategies followed by agribusinesses, input dealers and fertilizer companies are often product based and not productivity based.”37

Many important measures need to be taken collectively, a task that cannot be addressed by private input dealers or other private extension services:

the issues faced by the agricultural sector warrant collective adoption of management measures, such as in cases of pest and disease management in crop, livestock and fisheries (for example, foot and mouth disease of livestock); water quality issues; adaptive mechanisms against climate variability; market forces (price and market intelligence), agronomic requirements, etc. The management would be more effective upon wider adoption. Therefore, attributes like rivalry and exclusion—the major characteristics of private resources—are not facilitative in this context, and warrant presence of a public extension system.38

Finally, it is not the case that knowledge must flow solely from the scientists to the peasantry through the extension workers. The peasantry themselves are a vast fund of knowledge about the conditions, methods and needs of agriculture in their regions. Even when they spell out what is needed for improving their agriculture, social and economic conditions may prevent them from achieving these ends.39 These need to be learned from, and developed further in a scientific and democratic manner.

For example, it is often lazily assumed that tribal practices of farming are ‘backward’ and irrational, and must be abandoned for their own good. However, by studying these practices in their social context, Shereen Ratnagar brings out specific features of their sustainable use of land, viz., diversity of crops (including intercropping), the place of livestock, the careful use of forest wealth, methods of storage, and different types of subsidiary production. These have enabled the subsistence of the tribals against great odds.40 There is much that is to be learnt from these practices for India’s agriculture as a whole, if one first sheds the presumption that production for the market, and the commodities and methods dictated by the market, are the only solution.

Thus, not merely the quantitative multiplication of the public sector extension system, but its democratisation and qualitative improvement are required.

However, what is envisioned with the digitalisation of agricultural extension services is the sidelining or winding up of the public sector extension system, and its replacement with a completely unaccountable private corporate network, designed to serve the interests of its owners.

5. Added significance of public investment in the context of climate change

The World Bank and the Indian government envision the digitalisation of agriculture taking place on the basis of individual commercial transactions between a multitude of agricultural households and digital firms. However, as discussed above with regard to extension services, there are many questions which cannot be addressed individually, but require collective or State action.

Public expenditure is essential for the growth of private investment in agriculture.41 Without adequate public expenditure on irrigation, electrification, agricultural research and development, agricultural extension services, vaccination and veterinary services, public sector seed agencies, rural bank branches, rural roads, procurement and storage, poorer peasants may lack the surpluses to carry out their own investments, or may hesitate to invest due to the uncertainty of getting a return. The stagnation of public investment at low levels has contributed to the fall in private investment in agriculture; and therefore to the low levels of land productivity. It is small and marginal peasants, and those farming in rain-fed agriculture, that particularly need public investment.

The importance of public investment becomes even more starkly apparent in the context of climate change. Phenomena such as abnormal heat, irregular rains, droughts, floods, hailstones, cyclones and other unusual weather events will occur more and more frequently with climate change. Agriculture will witness changes in soil moisture, flooding and salinisation in coastal regions of western India, unpredictable increases in pests and weeds, changing timings and durations of cold and heat. Forest ecosystems face the prospect of irreversible damage. While the advanced countries focus the international discussion solely on actions that countries like India need to undertake to reduce emissions to mitigate climate change, there is virtually no discussion taking place on the measures needed for adapting to the climate change that is already certain to take place.

Indeed, the effects of climate change on India’s agriculture are already becoming apparent. Biswajit Dhar finds that the culprit for India’s third successive year of falling wheat production is heat: it is estimated that wheat production reduces by 4-5 million tonnes for every 1 degree Celsius increase in temperature. However, he notes, “fiscal support for agricultural research has remained inadequate as increases in budgetary allocations have often not been increased in real terms, which shows a lack of political commitment in this vital area.”42

As we pointed out at the start, India’s agriculture is largely composed of very small farms, practising subsistence farming. About 51 per cent of the net sown area is classified as ‘rain-fed’.43 Agriculture accounts for nearly half of all employment, and food makes up roughly half of consumer expenditure. All these facts carry grave implications in the context of climate change. Larger landholders, enjoying sizeable surpluses, may be in a better position to adapt to changes. But unorganised, poor peasants, who are barely keeping their heads above water, and lack surpluses for normal investment, are in no position to adapt individually.

Sizeable investments are thus required: to address new water-related issues, to develop systems and institutions to cope with emergencies, to improve weather prediction and communicate it to peasants, to develop new crop varieties and methods which can resist the new conditions, and (for all of this) to revive the severely depleted agricultural extension system. Further, various types of State support may be required in order enable diversification of crops to ones more resistant to the new climatic conditions. By their very nature, all these measures cannot be left to the market.

As we will see later, the Government’s base paper on digitalisation of agriculture does not even contain the words ‘climate change’.

6. Exploitative structure of marketing system

The abdication of public investment and intervention also leaves poor peasants at the mercy of exploitative forces. This can be seen with regard to in the agricultural marketing system. At the base of the system are the more than 23,000 Rural Primary Markets (RPMs), mainly the periodical markets known as haats, shandies, and fairs, owned and managed by different agencies such as individuals, panchayats, and municipalities.44 A Planning Commission report notes:

These are located in rural and interior areas and serve as focal points to a great majority of the farmers, mostly small and marginal, for marketing their farm produce and for purchase of their consumption needs. These markets, which also function as collection centres for adjoining secondary markets, are devoid of most of the basic needed marketing facilities….45

One haat caters to approximately 14 villages, with the majority of haats held in larger villages. Nearly two-thirds of the haats are held at a distance of 16 kms, 23 per cent at 6 to 15 kms, and 9 per cent within a distance of 1 to 5 kms, indicating the difficulty of transporting produce to the haats.46 “Very little efforts have been made so far by the government agencies/market authorities to develop the rural primary markets…. The standards weights and measures are not used at these haats. The exploitation of illiterate tribals/farmers by traders through wilful miscalculation and over-charging is a common phenomenon.”47

Cultivators receive better prices at the next tier of the marketing structure, that is, the wholesale assembling markets, run by Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMCs). However, the APMCs are generally located at district or taluka headquarters, important trade centres and railway stations. These are even further away than the haats, beyond the reach of most farmers. A NABARD study notes that

The small & marginal farmers, with uneconomical sized marketable lots, find it difficult to aggregate their produce and move to [APMC] markets to participate in the auction system for suitable price discovery. They, therefore, use local agents and traders, who relieve the small farmer of their produce at locally determined prices, to function as aggregators and transport to transact at the APMCs. This intermediation results in depriving the farmer-producers from aiming for optimal or market-linked price realization.48

By contrast with small farmers, “Rich farmers with higher surpluses generally take their produce to nearby wholesale assembling markets. At times, they purchase surpluses from other small farmers and carry the same along with their produce to the assembling markets for disposal.”49

Majority sell in local markets, without knowledge of MSPs or access to procurement

The National Sample Survey of farmers for 2018-19 confirms that the vast majority of cultivators sell their produce in “local markets” and to local private traders.50 (See Table 2, Appendix 3.) The data show that most cultivators are unaware about the Minimum Support Prices (MSPs), even in the case of the few crops for which substantial procurement is carried out.51 The minority of cultivators who are aware of MSPs are themselves largely unable to sell their crops at the MSP. Even in the case of paddy and wheat, in which there is significant Government procurement, more than three-fourths of the output is reported to be sold below MSP. (See Table 3, Appendix 3)

APMCs are deficient in infrastructure and dominated by middleman-trader cartels

The next tier of the agricultural marketing system is the wholeseale/assembling market, or secondary market, managed by APMCs. At present, there are 2,479 principal (APMC) markets plus 4267 sub-market yards, totalling 6,746 locations served by regulated markets. However, these are marked by two features. Firstly, they are woefully deficient in infrastructure:

covered and open auction platforms exist only in two-thirds of the regulated markets, while only one-fourth of the markets have common drying yards. Cold storage units exist in less than one tenth of the markets and grading facilities in less than one-third of the markets. Electronic weigh-bridges are available only in a few markets.52

Secondly, while the rationale of setting up APMCs was to allow government regulation, and thereby protect farmers from traders and middlemen, the APMCs are in fact generally run as cartels by the trader-middleman nexus. The commission agents function as

financiers, information brokers and traders, all rolled into one…. Agents are known to charge “more than just a commission” for the services they render. Many studies document non-transparent price discovery processes, often through collusive trader behaviour or hoarding as in the case of onions (Banerji and Meenakshi, 2004, 2008; Madaan et al, 2019). Consequently, farmers are reported to receive but a fraction of the price paid by the final consumer with middlemen cornering a large part of the rest (Mitra et al., 2013). More critically, the prices farmers get, coupled with low yields, are often inadequate to cover their costs or for servicing debts and meeting their consumption needs.53

Instead of fulfilling its responsibility of regulating the APMCs, breaking the trader-middleman nexus, and ensuring cultivators receive a remunerative price, the Government cynically cited these malpractices as a justification for enacting the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020. This was one of the three ‘Farm Acts’ against which kisan organisations waged a year-long struggle. The aim of this Act was to bypass the APMCs altogether and allow unregulated private procurement by traders and corporations, thereby rendering cultivators even more defenceless. After the withdrawal of the three Acts, the Government has simply allowed the existing woeful state of the APMCs to continue.

While the Government uses the deficiencies and malpractices of APMCs as a pretext for winding them up, it emerges that, despite these deficiencies, cultivators receive higher prices in the APMCs than they would otherwise. A recent RBI study shows that farmers receive higher prices in regions with a greater density of regulated markets (i.e., higher ratio of APMCs to villages in the district): “improving spatial competition and the availability of better infrastructure amenities in agricultural markets or mandis, can reduce traders’ mark-ups and ameliorate farmers’ market access. This finding is consistent with studies highlighting that farmers are more likely to realise higher prices in regions with a higher mandi concentration.”54 The figure of APMCs, however, has stagnated, as the Government has pursued its agenda of winding down the APMC system and promoting the setting up of private yards.

Table 1: APMC Markets and Sub-yards

| Principal markets | Sub-yards | |

| 2005 | 2428 | 5129 |

| 2017 | 2479 | 4267 |

The RBI study finds that growers of perishable commodities tend to receive a lower share of the consumer price than in the case of non-perishables. This may be due not only to wastage, but the larger share taken by middlemen, who take advantage of growers’ lack of holding capacity. The market for fruits and vegetables is marked by the crashing of prices during the peak season. Growers (particularly small and marginal farmers) are forced to dispose of their crops at prices so low that at times they do not even cover their cost of production. Those who have taken loans for costs of cultivation are under even greater pressure to sell. The price disparity between peak and lean periods can range up to 100-150 per cent. The market is controlled by cartels of traders and agents who command large cold storage capacity spread over different states, and are thus capable of regulating the supply of fruits and vegetables to different markets.56

Despite this well-known reality, the State makes negligible effort to systematically intervene in these markets. It has failed (1) to set up cold storages in the public sector, for use by peasants, which would have given the peasants greater holding power; (2) to help peasants preserve and store produce on-farm, where possible; and (3) to help local processing of fruits and vegetables by peasant collectives, to enable them to obtain better returns. As can be seen from Table 2, cold storage is almost entirely in private hands.

Table 2: Sector-wise Availability of Cold Storage Capacity

| Sector | Number | Capacity (lakh tonnes) |

| Private | 4243 | 185.32 |

| Cooperative | 394 | 9.75 |

| Public | 125 | 0.82 |

| Total | 4762 | 195.89 |

The above description of the marketing system has important implications for digitalisation, as we shall see below.

7. The first phase of digitalisation: commodity futures markets

It has been an established norm for the State to protect farmers from risks of different types. This has been the outcome of innumerable organised and spontaneous struggles of the peasantry over the years. For example, the State announces Minimum Support Prices for various crops, carries out public procurement of certain crops, and distributes the procured crops through the Public Distribution System. This is intended to protect farmers (and consumers) from price fluctuations. The State provides provides compensation and/or loan waivers at times of crop loss due to natural calamities, such as drought, flood or pest attack. It is true that MSPs are too low, procurement is only of a few crops in certain areas and not universal, and compensation is generally inadequate; but that does not negate the importance of the norm. Indeed, farmers consider it a right to receive such protection, and frequently wage agitations to demand higher MSPs, procurement of crops or compensation for losses.

However, in the world of neoliberal imagination, all risks can be expressed in financial terms, and all parties can protect themselves individually against these risks through financial mechanisms. These mechanisms can be used in place of State intervention and public sector investment. One such mechanism is insurance: the data show that hardly any farmers insure their crops on their own initiative, and only a quarter of those that do so receive any part of their claims.58 Another such mechanism is commodities futures markets.

In the early 2000s, neoliberal economists and the Government actively promoted the notion that farmers could insure themselves against price volatility by trading on the agricultural commodity futures market. Futures markets are markets in which parties contract to buy or sell a particular (standardised) quantity at a specified date in the future, at a price determined in advance between the two parties. This contract, for a standardised quantity of a standardised commodity, is then traded on the market like a share on the sharemarket. No physical delivery takes place; the contract is settled by payment.

Neoliberal economists claim these markets aid in ‘price discovery’, with buyers and sellers in competitive markets efficiently determining the true market price; and enable ‘hedging’, a method of reducing risks. Futures trading, we are told, helps minimise uncertainty and makes prices less volatile, thereby enabling farmers to take informed decisions on what to grow. Apart from producers and consumers, it is considered necessary that speculators too participate in these markets, for that would ensure enough liquidity. Farmers can participate in these markets to insure themselves against a rise in the price of inputs or a fall in the price of their crops. The futures market is, in fact, an early form of digitalisation in agriculture, accompanied by the same mythology.

However, contrary to the propaganda, (1) India’s agricultural commodities markets are dominated by speculators, not producers or consumers, and are subject to volatility; (2) this can lead in turn to price surges for consumers, without any benefit for the farmers; (3) as a result, the Government has been forced to ban futures trade in specific commodities from time to time; (4) thus, three decades after liberalisation, the futures market for agricultural commodities is still limping.

Not all agricultural commodities lend themselves to being traded on future exchanges,59 but even in the case of traded commodities, few farmers participate in futures markets. “Multiple factors like high speculation, high margin amount required for futures trade, low quantity and quality of output, imperfect information about the functioning of futures market, low warehouse facilities, the low level of understanding about the market, and so on contribute to the low farmer participation as hedgers in the futures market exchanges.”60

The experience of farmers with commodity futures markets brings out certain important lessons with regard to digitalisation and agriculture. Digitalisation intensifies the process of financialisation, in which real activities and physical commodities (i.e., use values) get converted into ‘data’ and made into financial assets. These assets become the means for uncontrolled financial speculation and parasitism. The peasantry is unable to intervene in, let alone benefit from, this process.

Let us now turn to the Government’s programme of digitalisation of agriculture.

II. The Programme of Digitalisation of India’s Agriculture

The case for digitalising agriculture is laid out in a World Bank report, What’s Cooking: Digital Transformation of the Agrifood System.61 The report is cited by the Indian authorities at the outset of their own base paper for the digitalisation of India’s agriculture, to which we will turn later. What’s Cooking provides a useful summary of the state of research on the subject. (In Appendix 1 at the end of this article, we review the report.)

Briefly: the report begins by making sweeping claims of the benefits of digitalisation to farm efficiency; farmers’ access to markets and finance; the efficiency of Government policy; and the environment. Private firms would provide farmers guidance (on agricultural practices, choice of crops, choice and quantum of inputs) tailor-made to their individual farms; provide them credit tailor-made to their financial needs; guide them to obtain the best prices for their crops; enable storage, logistics and even processing – all, of course, for a fee, as the entire activity is to be driven by the profit motive. These benefits are to be provided exclusively by private firms. The role of the State is to create an “enabling environment”, for which the report provides a long list of jobs for the State to carry out.

However, the body of the report at various points concedes that there is little or no evidence for these claims of the benefits of digitalisation. Instead, the report concedes the following:

(1) The market power of incumbent digital corporations tends to keep growing as they acquire more data. Access to farmers’ data will strengthen the negotiating power of private firms vis-a-vis the farmers.

(2) Digital agriculture is unsuitable for smallholder farmers, and income/land inequality may increase in the course of its advance.

(3) The digitalisation and linking of various types of data may render small farmers more prone to predatory activity by corporations.

These observations, as we shall see, are relevant to India’s programme.

The IDEA “Architecture”

The Indian government’s plans for digitalising India’s agriculture are laid out in Transforming Agriculture: Consultation Paper on IDEA (June 2021).62 Citing the World Bank report’s recommendations, it calls for the “digital transformation” of India’s agriculture. It ends by framing certain questions for “consultation” with the public, such as: “Is the idea of IDEA necessary for India’s Agriculture ecosystem?” and “Is IDEA feasible”? There is no indication that the authors themselves have considered these questions. At any rate, the “Consultation” was for form’s sake. Implementation was underway long before the Consultation Paper was released.

It is clear from the outset that the starting point of IDEA is not India’s agriculture or its agrarian classes at all. Rather, the starting point is a framework laid down by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY). This framework, named “InDEA 2.0”, which “has formulated a comprehensive set of principles for guiding the design of digital ecosystems…. The set of InDEA 2.0 principles is proposed to be leveraged for designing the IDEA Architecture.”63

We have discussed “InDEA 2.0” in a little more detail in Appendix 2. In essence, InDEA 2.0 lays down a standard framework for ‘digitalising’ various sectors, such as health, education, agriculture, and so on. In place of the Government providing services, and being accountable for doing so, InDEA 2.0 prescribes that the Government should enable an ‘ecosystem’ to allow private digital firms to deliver these services to citizens. The Government’s role is restricted to creating digital identities for citizens (specific to each sector); setting up platforms through which they can connect with private firms; and creating datasets to which private firms would be given access. The ecosystem of private firms and citizens themselves is to do the rest, growing in an ‘organic’ fashion (i.e., on its own) and on a commercial basis. Under the cover of digitalising various sectors, then, what is being implemented is their privatisation, and the abdication of the role of the State.

The India Stack model

The IDEA paper is thus the application of this model, i.e., the ‘InDEA Digital Ecosystem of Agriculture’. A glance at the two documents reveals that the InDEA framework has been transplanted virtually intact into IDEA, chapter by chapter, diagram by diagram, with hardly any adjustment for its application to agriculture. It abounds with terms such as ‘interoperability’, ‘access to information’, ‘data governance’, ‘data quality’, ‘data standards’, ‘security’, ‘innovation’, ‘value nodes’, ‘building blocks’, ‘agile architecture’, ‘cloud first’, ‘registries’, ‘directories’, ‘IoT (Internet of Things)’ and ‘sandbox’.

By contrast, the following terms are not to be found, or are only cursorily mentioned, without discussion, in the document. Yet these are indispensable for any discussion of the life and labour of India’s peasantry.

Table 3: Mentions of Agriculture-related Terms in IDEA Consultation Paper

| Term | No. of mentions in the text |

| Loan, debt, lender, usury, interest (on loans), suicide | 0 |

| Credit | 1 |

| Trader, merchant, dealer, remunerative, Minimum Support Price/MSP, deficit | 0 |

| Class, tenancy, caste/Dalit, tribal/Adivasi, women | 0 |

| Forest, forestry, forest produce, etc | 0 |

| Commons, common lands, common property resources | 0 |

| Climate/climate change | 0 |

| Well/borewell | 0 |

| Irrigation | 2 |

| Water | 2 |

| Fertiliser | 2 |

| Seeds | 2 |

| Pesticide | 2 |

| Horticulture | 1 |

| Animal husbandry | 2 |

| Veterinary | 0 |

| Fish/fisheries | 2 |

| Bees/bee-keeping, sericulture, vermiculture | 0 |

| Poultry | 1 |

| Pastoralism | 0 |

Even the few mentions of these terms in the IDEA paper are perfunctory. “Credit” is mentioned only in a table providing an “Illustrative list of Value-added & Innovative services”. Irrigation, fertilisers, and pesticides are mentioned in something called a “List of domain standards”. Water, seeds, fertilisers, and pesticides are mentioned in a sentence talking of enhancing input efficiencies by “providing easier access to information”.

In a striking evocation of colonial autocracy, the document was published in English alone.

As described in Box 1 below, IDEA is essentially an extension of the India Stack, that is, a digital ‘infrastructure’ which allows individuals and digital firms to interact with each other. Since farmers are treated as if they were profit-maximising firms, it is assumed that they can take care of their own interests, and find the best commercial solutions for their problems, without State intervention and public expenditure.

BOX 1

The India Stack model applied to agriculture

In essence, the model presented by IDEA is that of the ‘India Stack’, which we described in Part 1 of this series of articles. To recap, ‘India Stack’ serves as the overall digital infrastructure for India’s digitalisation drive. It enables individuals and myriad software applications to connect with one another through a single unified software platform. It consists of three layers:

(1) establishing identity (Aadhaar);

(2) payments systems (Unified Payments Interface, Aadhaar Payments Bridge, Aadhaar Enabled Payment Service), and

(3) data exchange (DigiLocker and Account Aggregator).

This infrastructure, created at State expense, acts as a subsidy for the private sector and provides it a vast mine of data, most of it being the private data of citizens. The base of the entire project is the Aadhaar project, set up at high speed without any legislative backing. As Nilekani observed, “We felt speed was strategic. Doing and scaling things quickly was critical. If you move very quickly it doesn’t give opposition the time to consolidate.”64

(1) Corresponding to the Aadhaar, IDEA begins with the creation of a “Unique Farmer ID (UFID)”, a unique number assigned to every farmer. For this the Government will create an all-India digital database of farmers based on land revenue records. The digitalisation of land records is proceeding hectically for this purpose. In her Budget Speech of July 23, 2024, the Finance Minister declared:

Buoyed by the success of the pilot project, our government, in partnership with the states, will facilitate the implementation of the Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) in agriculture for coverage of farmers and their lands in 3 years…. The details of 6 crore farmers and their lands will be brought into the farmer and land registries.

Like Aadhaar, the UFID may be required for farmers to get access to various goods and services, such as subsidised fertiliser, PM-Kisan payments, bank loans, and so on. As a result, while nominally voluntary, it will become, like Aadhaar, mandatory for all practical purposes. At the same time, those who are excluded from the UFID may be excluded from various rights and entitlements. We are familiar with such exclusions in the case of Aadhaar, where large numbers of the poor have been denied even rations in the public distribution system.

(2) Corresponding to the Unified Payment Interface (UPI), which is used for digital payments, IDEA is to set up a Unified Farmer Service Interface (UFSI), through which the farmer and the private firm would connect with each other.

(3) According to the IDEA paper,

the apparent and latent value of data is not exploited to any significant extent currently for several reasons like (a) lack of qualitative data (b) incomplete datasets (c) lack of an organized and trustworthy system for exchanging of data and (d) lack of interoperability standards.

IDEA proposes to address all these challenges systematically by promoting the establishment of “Agri Data Exchange(s)”.

In this framework, farmers would continuously churn out data through every transaction they enter into: receiving a Government transfer payment, taking or repaying a loan from a bank or digital lender, purchasing inputs, selling their crops, and so on. Since their UFIDs are linked to their land, a drone survey can monitor the condition of, and activity on, the land.

Once the digital public infrastructure for agriculture has been set up, farmers would transact with private corporations to gain access to credit; make their input use and farming methods more efficient; protect themselves against various types of environmental stress and hazards; improve their access to, and returns from, output markets; and thereby increase their profits. Indeed, the entire model would be driven by the desire of farmers and corporations to make profits; and yet their individual profit drives would produce the best possible outcome for economy as a whole. Clearly, it is steeped in free-market ideology, not in the realities of India’s agriculture.

Implications of the IDEA framework

Let us now turn to the implications of what is presented in the IDEA Consultation Paper. Invaluable work has been done by the Internet Freedom Foundation, ASHA Kisan Swaraj, and other organisations in analysing the IDEA document, as well as the overall process of digitalising agriculture, and alerting the public to their implications. (Readers can visit https://internetfreedom.in/iff-response-to-the-idea-paper-on-agristack/, where they will find links to number of resources on the subject. These include a Joint Submission on the IDEA paper, endorsed by 90 organisations, which provides an overview of the subject. A list of Resources on Digitalisation can be found at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/18GhcC2ZEZYjr8KVTswKYbYQVqsydycXx/view. A video explaining the technical jargon of IDEA in simple terms can be found on the Youtube channel of ASHA Kisan Swaraj, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IUzs9_LqR7g,. Interested readers can join the mailing list of this network, by writing to

[email protected], from which they will receive regular updates on the digitalisation of agriculture in India.)

Below, we summarise some of the observations made by the above organisations and networks.

Corporate control

(1) Implementation of the IDEA paper began even before the ‘consultation’ process began, through the signing of Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) with several corporations, including some of the world’s largest or India’s largest. Among them are Microsoft, Amazon, Cisco, Jio, ITC, Patanjali, Ninjacart, Agribazaar, NCDEX, Esri India, and Star Agri. While these were pilot projects, they were preparatory to full scale development.

— Microsoft was given the task of building the Unified Farmer Service Interface (UFSI), the underlying digital infrastructure, using farmers’ data, including Government scheme data and land records, to authenticate their identity.

— Amazon would create a ‘start-ups ecosystem’ for apps, using Government data on farmers.

— Patanjali was to create ‘farm management solutions’ using precision agriculture.

— Agribazaar would create a marketplace for agrifinance, agri-inputs and produce, and build a farm databank.

— ITC would provide customised crop advisories for the wheat crop.

— Jio too would provide farm advisory services.

— Ninjacart would develop a market platform for post-harvest produce.

— Cisco would develop intelligence from the Internet of Things devices and satellites.

These MoUs provide these firms an opportunity to advance their interests through the design of the core elements of the digital infrastructure. If these contracts are confirmed on the basis of these pilot projects, they will be provided with extraordinary gifts of data. As the joint submission of 90 organisations points out, the very ownership of IDEA/AgriStack and its various components is unclear, and allows for private corporations to control both data and structure.

No one can be under the illusion that these firms are engaged in some sort of public interest activity. Microsoft, Amazon, and Cisco have been sued by the US government itself for monopolistic practices. India’s Parliamentary Standing Committee on Finance, in its December 2022 report, “Anti-Competitive Practices by Big Tech Companies”, documents their practices in India as well. Reliance Jio rose to the top through a four-year cutthroat price war backed by its massive financial clout, driving most rival telecom firms to closure or merger, and reducing the sector to a near-duopoly. ITC, Agribazaar, Ninjacart and Patanjali are already in the business of procuring from farmers; yet the data of farmers and the design of agricultural marketing are to be turned over to these very firms. As American economist Milton Friedman made clear (in what became known as the “Friedman doctrine”), “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits”, and thereby serve the interests of the firm’s shareholders, not to serve the interests of the public.65

Indeed, as the Joint Submission points out, in the IDEA framework

there are no safeguards in place to ensure the economic interest of farmers. If an unethical actor in this digital ecosystem cheats or takes unfair economic advantage of a farmer through a service or a transaction, there is no grievance redressal mechanism in place. There is no talk of methods to log complaints, or how redressal will be accessible to a marginal farmer. How are actors in this digital ecosystem to be held accountable for their actions?66

Indeed, digitalisation is being presented as a method for the State to abdicate its responsibilities in relation to agriculture, leaving the peasantry even further at the mercy of private interests.

For example, the Government and the RBI are now presenting digital lending as a solution to the problem of extending agricultural credit – a job that public sector banks have been tasked with till now. We get a glimpse of the actual impact of such digital technologies from a study of a start-up, Dvara E-Registry, which, by “harnessing a variety of technologies like mobile and GIS and the power of Machine Learning… aspires to enable the rural under-banked to participate seamlessly in the mainstream financial marketplaces and facilitates customisation of banking and insurance products.”67 Srikanth Lakshmanan points out that Dvara surveyed 1871 farmers in Keonjhar and Jajpur districts of Orissa; it shortlisted 984 for credit advice; it completed credit appraisal of 238; of them, 147 were found to be eligible; using Dvara’s technology land of 87 farmers was digitalised; loans were disbursed to just 7 farmers.68

Digitalisation of land records: erasure and capture

(2) The “centralised farmer database” is to be based on land revenue records. As we saw in our discussion of agriculture above, large sections of cultivators would be excluded by such a procedure: women farmers, tenant farmers, sharecroppers, landless peasants, and forest dwellers. Those in allied industries such as fishing, bee-keeping, poultry, forest-gathering, animal husbandry, pastoralism, sericulture, vermiculture, and agro-forestry too would be excluded.

Finally, the existing land records are ridden with problems, including false records, contested claims, and multiple uses of land, often customary rather than documented. The process of digitalising these severely compromised records provides an instrument for the powerful and propertied to dispossess oppressed sections. The Joint Submission observes that “when it comes to a divergence between hard copy land records and the digitised version, the latter is prevailing and not the former.” Once a digital record is created, it becomes in practice much harder to correct, since the physical presence of a local official is replaced with a remote non-person: “The aspiration of making governance ‘presence-less’ often translates into a reality that makes governance disappear for the average farmer.”

In September 2017 the Telangana government initiated a ‘Land Records Updation Programme (LRUP)’ to “purify” its land records. A study by R. Ramakumar and Padmini Ramesh reveals that the process was marked by intense conflict: a deluge of complaints regarding errors and exclusions, widespread allegations of corruption, absence of grievance redressal, and suicides by dispossessed peasants. The Government’s claim to have “purified” its land records was illusory: “A purity level of 93% only meant that new data were entered into 93% of the land records based either on the previous entries or on the responses received from persons whom the government assumed as the real landowners.” As the opposition to the LRUP threatened to metamorphose into a major political storm, the programme ended in a stalemate. The authors conclude:

The problem, we argue, is that the neoliberal state envisages land records modernisation as an erasure of history, in disregard of egalitarianism in land distribution and under the assumption that the ‘illegibility’ of records is a technical problem of administrative dysfunction. Aided by technocracy, the neoliberal state seeks to flatten out the historical multiplicities of claims and counterclaims on land; in their place, it superimposes a new system, actively intermediated by poorly designed portals, which essentially puts in place a new set of claims inadequately vetted by democratic exercises and laced with a new logic of power. The complete exclusion of tenants from the LRUP in Telangana is an illustration. All grievances hit a dead end, with an impersonalised portal absorbing complaints with no accountability to respond—either effectively or in time.69

An important aspect of the Central government’s drive to digitalise land records nationwide is its attempt to shift from the existing system of presumptive titling to a system of conclusive titling. Under the former, the existing landholders’ documents are taken as evidence, but are open to legal challenge; under the latter, the title is not open to legal contest, and is enforced by the State. Institutions such as the World Bank argue that conclusive titles facilitate the sale of land, and thus enhance the ‘ease of doing business’ for private investors. In this fashion, the digitalisation process may result in an intensification of class war, from above.

Locking in the farmer

(3) As with the Aadhaar, the IDEA framework includes certain ‘consent’ rituals. Among its components is an (aptly named) ‘Consent Manager’, which has been “Developed to comply with the Consent requirements under the privacy laws”. This provides for the farmer to provide consent for the sharing of private data. However, since access to various services is to be made contingent on providing consent, in practice there is little choice.

Such data may arm the firm with critical information about the farmer, worsening the latter’s bargaining position. For example, if a firm procuring vegetables has access to the farmer’s bank account data and indebtedness to various lenders, it is in a better position to dictate prices. Drone surveys may also be carried out without the farmer’s permission. If the firm is dominant in a particular market, either commodity-wise or region-wise, further information about the farmer can only work in the firm’s favour, not the farmer’s.

Indeed, in order to believe that digital firms will operate benevolently towards farmers, we need to suspend our knowledge of these firms’ actual functioning. The Joint Submission points out that, once consent is obtained on certain terms of engagement, and the user is locked into a particular service, the terms can thereafter be changed. The ritual of consent can even be performed once more, if necessary, since the user has no real choice. Taking the example of how Ola and Uber have operated, the submission envisions

a scenario where an e-commerce website ties up with a farmer offering to connect them directly to consumers, like ride-hailing apps promise to connect drivers with riders. Such an e-commerce website may initially even offer good rates to farmers, like the ride-hailing apps initially offered good rates to drivers. Once the traditional post-harvest supply chain of the farmers is broken and the farmers have no choice but to supply to the e-commerce company, the e-commerce websites could start paying the farmers less. They will also use the knowledge gained from the artificial intelligence to surge price consumers for the food they are buying from the underpaid farmers.

III. In Conclusion

Above we have briefly presented the conditions in which the digitalisation or ‘digital transformation’ of India’s agriculture is being planned and implemented. The IDEA paper is premised on a distorted understanding about both private corporations and the mass of India’s peasantry. On the one hand, the IDEA paper treats the vast mass of India’s peasantry as profit-maximising units, along the lines of private firms; but it presumes the opposite for private corporations, treating them as promoting public welfare.

Thus the IDEA paper makes the unjustifiable assumption that, if digitalisation makes possible certain benefits to farmers, private corporations will automatically undertake to provide the farmers these benefits. However, private corporations are formed and operated to pursue profit for those who own them. Corporations which have commercial transactions with farmers stand to gain by using data and information technology to extract the maximum possible profit from the latter. The long history of private corporations does not reveal many instances of firms which pursued the public interest against their own profit.

Further, it is strange to imagine that private corporations would promote environmentally sustainable practices. In general, environmentally sustainable practices are not profitable for private corporations to pursue or promote, which is precisely why such practices are not already prevalent. Protection of the environment requires action by the State, or by a people’s movement; it can hardly be left to the market. We are compelled to make these glaringly obvious points because the entire project of digitalisation is premised on such absurdities.

It is equally unjustifiable, as we have discussed at length, to treat the mass of India’s peasantry as homogenous profit-maximising units. Above, we have described the following situation:

— The vast majority of India’s farmers, with very small holdings, are driven by the need for subsistence, rather than profit, even when they grow crops for sale. They do not enjoy freedom of choice; rather, they face multiple compulsions. Their so-called ‘uneconomic’ holdings do not yield enough for their subsistence; thus large numbers of peasants also work as wage labourers or carry on petty businesses in order to put together a living. So scarce is employment (i.e., so far is the labour market from ‘clearing’) that, in the last few years, employment in agriculture has risen as a share of total employment, with income per worker going down.

— Large segments of the peasantry operate in a legal twilight, excluded from land altogether, or from titles to the land that they work on, or possessing only insecure titles, which may be snatched away at any time.

— Incomes from cultivation of crops have been falling in real terms. The growing indebtedness, and consequent suicides, are expressions of the fact that peasants, far from being driven by profit, are trapped in their existing conditions, and see no way out. They know the dangers of environmentally unsustainable practices, but are not in a position to individually dispense with them. They are unable to carry out productive investment. Thus investment in agriculture, as a percentage of GDP generated in agriculture, is falling. The vast majority of peasants either lack access to technical advice, or do not have reason to trust it, or are unable to follow it due to other compulsions. To the extent they seek and obtain advice, they do so from other farmers or from input dealers. By now the systematic withdrawal of the State from the protection and development of peasant production has rendered the peasantry even more helpless.

— Private input dealers are today the main form of agricultural extension services actually operating. Traders providing inputs or purchasing the produce may also provide credit, often binding the small farmer’s hands in the choice of crop, use of inputs, and the sale price of the crop. The marketing system is marked by extreme backwardness of physical facilities and logistics, cartels of traders/middlemen, and the helplessness of the majority of peasants. The process of aggregation and movement of agricultural produce still must travel through this physical network, irrespective of any ‘virtual’ networks created by digitalisation. Finally, the commodities futures market, an initial foray of digitalisation in the agriculture sector, has proved to be a playground for speculators rather than a ‘perfect market’ for farmers.

It is on such a reality that the Indian State is proceeding to impose digitalisation, touting it as a magical solution.

The nature of India’s agriculture imposes certain limits on the market for digital firms. However, to the extent these firms create and extend their market, they will have the effect of increasing inequality.

Firstly, to the extent larger farms carry out automation using digital technology, the employment of agricultural labour would shrink. This is in a situation in which real rural wages have already been declining for the last few years, due to the lack of employment.

Secondly, the increased power of corporations, through access to data, would enable them to squeeze the peasant more. Already, the terms of trade for farmers have been declining for the last few years. The increased pressure on peasants’ earnings may compel a section of them to part with their land. Indeed, this would be a gain for private corporations, as it costs them less to deal with a smaller number of large farmers than to deal with a multitude of small farmers. The process of concentration of land in the hands of large farmers would also enlarge the market of corporations in this sector. However, by depressing peasant and labour incomes in general, it would accentuate the demand crisis in the Indian economy.

Our position regarding the entire project of digitalisation of agriculture

What position should peasant organisations take regarding the Government’s project of digitalising agriculture? The facts and analysis presented by the Internet Freedom Foundation, ASHA Kisan Swaraj, and others are quite damning, and we recommend that all those interested in India’s agriculture, and indeed its national and developmental interests, study these materials.

We have only one serious reservation: namely, that, given these very documents and arguments, it is unwise to propose changes to the present framework, even as a form of engagement. Rather, it is necessary to reject and oppose the entire present project of digitalisation of agriculture. As the authors of the Joint Submission point out, “not all the solutions [for the problems of agriculture] are rooted in technology.” Moreover, as they correctly observe, technologies “can be put to both good and bad use.” What is being done here is clearly the latter.

The authors of the Joint Submission are quite correct to demand that every individual must have control of his/her own data. They list the elements of meaningful consent: prior, informed, free, revocable, granular and limited consent. However, the experience of Aadhaar, as well as of credit scoring bureaus, tell us that the Government’s entire digitalisation project is based on ‘consent’ that is obtained forcibly, surreptitiously, irrevocably, and without limits.

This is not to argue that there are no uses for digital technology in agriculture, as in any sphere of the economy. Rather, we are arguing the following:

— As is clear from our brief account of the conditions in India’s agriculture today, the major problems are rooted in social-economic relations (class relations) and State policy, and the resolution of those problems does not require digitalisation. The existing land relations, system of credit, lack of extension services, decline of investment, exploitative market structure, and environmental degradation can all be addressed through social action – either by the State, acting under pressure from peasant movements, or by the direct action of peasant movements. Indeed, these are largely incapable of being resolved without such action. Peasant organisations have been struggling on these questions for many decades, and that struggle will continue.

— The purpose of the digitalisation programme is not at all to solve these problems of agriculture, but to render the sector more amenable to financialisation, intensified exploitation and corporate takeover. By ‘financialisation’ we mean, in this context, the conversion of material things and ‘real’ activities into ‘data’, and thereby into financial assets, which can be traded (and used to generate yet more financial assets); and the consequent deeper penetration of finance into real economic activity. The digitalisation of land enables each land parcel to be treated as a financial asset, and facilitates the transfer of these assets to investors, especially in conditions of peasant distress. The creation of digital identities enables digital corporate firms to capture and link all the data available about a peasant, thereby exercising greater control over him/her (recall that as land is digitalised, farmers’ ‘identity’ is linked to ownership of specific land parcels). The digitalisation of agricultural marketing enables private corporations to obtain greater information about not just the produce but the producer. The digitalisation of extension services, on the one hand, treats information (advice), which was hitherto treated as a public good, as a financial asset to be sold to the farmer; at the same time it allows the capture of valuable individualised farm-level information which can be used for the firm’s gain, or sold to other firms. The digitalisation of credit replaces the earlier developmental framework for rural credit. (In that framework, the extension of bank credit to agriculture was acknowledged to be a developmental imperative, intended to displace the parasitic extractions of usurers, improve the earnings of farmers and promote productive investment in agriculture.) Instead, under digitalisation farm loans are treated as pure financial assets, with the quantum and interest rate determined by the borrower’s ‘credit risk’ alone.

It is therefore in the interests of all peasant organisations to oppose the project as a whole, and unconditionally.

Actual outcome would be shaped by the specific conditions

The actual outcome of the digitalisation project in India’s agriculture will take place within the constraints prevailing in India’s agrarian sphere. Neither will the present problems of India’s agriculture be magically overcome by digitalisation, as the proponents of digitalisation claim. Nor will the complete corporate takeover of agriculture, and the ejection of the vast peasantry, be easily achieved.

Since small and marginal farmers have remained on the farm for lack of employment outside agriculture, any attempt, direct or indirect, to oust them will face their resistance, both organised and spontaneous/unorganised; the experience of the attempted digitalisation of land records in Telangana bears this out. To the extent that vast numbers of small and marginal peasants still cling on to their land, private corporations will still need to use various intermediaries, such as the present traders and arhtiyas, to reach the actual producers. Digitalisation as such does not change the backwardness and distortions of the existing market structure and physical infrastructure; rather, digital corporations may find it useful to work through the existing networks, and peasants too may have little option but to work through them.

Small and marginal farmers may get included in the databases of private firms, either voluntarily or involuntarily. But given their problems of lack of ‘digital literacy’, indebtedness to specific local traders, small lot sizes of produce, lack of quality certification, and high transport costs, they would probably continue to depend on various types of intermediaries, rather than directly deal with private firms.

The digitalisation of credit, as we have seen earlier, may not result in any increase in the flow of credit to productive activities in agriculture. Hence the scope for usurious extractions may continue.

Finally, the local power structures and social relations in the rural areas, which have maintained ruling class hegemony there for the last three-quarters of a century, can hardly be dispensed with. The change is that corporations can use the latest information technology, and their greater access to data, to exercise greater control over the entire structure, and step up their extractions from it.

However, peasants may not remain the passive objects of State policy, corporate strategy and local domination. They have proved, over and over in the course of history, that they are active subjects, capable of shaping their own destiny. The coming period may witness their response to this latest attack.

Appendix 1: The World Bank on the Digitalisation of Agriculture: A Closer Look

A recent World Bank report, What’s Cooking: Digital Transformation of the Agrifood System,70 makes the case for digitalising agriculture. Indeed, it is cited by the Indian authorities at the outset of their own base paper for the digitalisation of India’s agriculture, to which we will turn later. What’s Cooking provides a useful summary of the state of research on the subject.

The World Bank’s claims and prescriptions