In the following two parts, we argue that there is a contradiction between the character of India’s economy, on the one hand, and the present drive of digitalisation, on the other. Even as India’s rulers claim to be advancing it to ‘developed’ or even ‘superpower’ status, the country actually remains in the grip of retrogressive social and economic institutions. The present digitalisation drive leaves India’s retrogressive social institutions in place, and claims to overcome various hurdles to development through purely technological means. In reality, it equips the corporate sector and various retrogressive social forces with additional instruments to carry out both intensified exploitation and outright expropriation (i.e., grabbing of assets).

Digital technologies no doubt bear enormous potential for humanity, and there are innumerable positive uses to which they can and must be applied. However, at present, these technologies are by and large not under the democratic control of the people. Hence they are being deployed in a fashion that serves the interests of the corporate sector, domestic and international, not the interests of the people.

This is not surprising: when capitalists deploy new technology, they do so in their own interests. This is not unique to India. However, in the specific conditions of India, the disjunction between the technology being deployed and the economic and social conditions of the people is so extreme that the impact is particularly grave, involving in many cases depredation or outright dispossession.

We pursue this theme through an examination of two sectors, namely, digital lending; and agriculture.

The role of finance in neoliberal ideology

This contradiction can be seen in the ‘fintech’ sector, and in particular in its digital lending applications (DLAs). In the following, we take a brief look at the financial condition of the people, the growth of DLAs in that situation, and the results of this development.

Finance occupies a key role in neoliberal ideology. The neoliberal ideal is a ‘free market’ in which atomised individuals interact to produce optimal outcomes. Typical is the statement of a Chief Economic Advisor that, if subsidies could be eliminated, India would attain “Nirvana… prices in India will be liberated to perform their role of efficiently allocating resources in the economy and boosting long run growth”.1 Finance provides the mechanism for this interaction: when all persons have access to finance, they can all participate in the market, and so the outcome will be Nirvana.

As working people find themselves in fact excluded from their traditional resources and from the surpluses generated in the present pattern of development, the rulers have been increasingly insistent on these very people being financially ‘included’. As one study notes, the concept of ‘financial inclusion’ became central to Indian policy making precisely when “it became clear in the early 2000s that fruits of the reform measures since the economic liberalisation of the early 1990s were not flowing to the disadvantaged”.2

While different authorities use different definitions of financial inclusion, they hinge on the notional access to finance. For example, the 2023 IMF study on India’s digitalisation3 measures the extent of ‘financial inclusion’ simply by the percentage of the adult population with bank accounts. How much those accounts contain, how frequently the account holders transact through them for their own needs, what share of borrowings are done through those accounts – all these do not figure in its measure of ‘financial inclusion’.

Further, the authorities advocate digital lending on the claim that it will complete the unfinished agenda of ‘financial inclusion’. A report by a Reserve Bank of India (RBI) think tank claims that digital lending “can deliver services at significantly lower costs, enabling financial inclusion of hitherto unserved households.4 The RBI’s Working Group on Digital Lending (WGDL) repeatedly asserts that “Digital finance has been instrumental in making significant strides towards financial inclusion.”5 However, no data are provided to back up such claims.

Actual financial state of the people

Some recent official reports provide glimpses of the actual financial state of the Indian people. These belie the notion that Indian households are ‘financially included’.

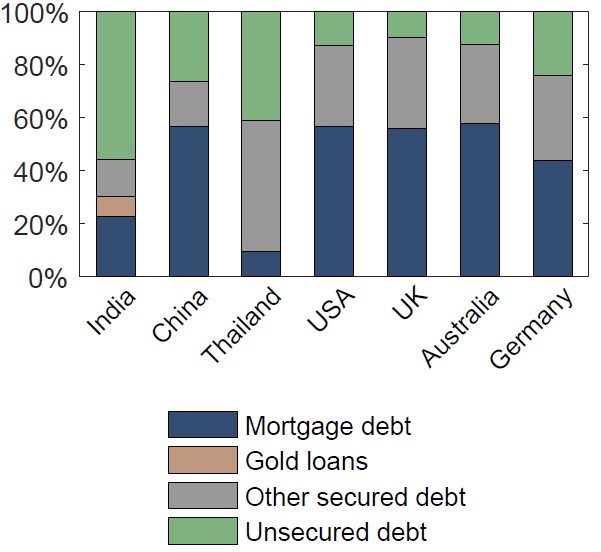

In fact, a very small share of the wealth of ordinary Indians is in financial form. The report of the Household Finance Committee (HFC)6 noted that the overwhelming bulk of the wealth of Indian households is in the form of physical assets – in particular, 77 per cent in land and buildings, 7 per cent in other durable goods, 11 per cent in gold, and the residual 5 per cent in financial assets. Further, according to the HFC, most Indian household debt is unsecured (56 per cent), which also reflects a high reliance of Indian households on informal, non-institutional sources of lending such as moneylenders and intra-family loans. Within secured debt, gold loans are significant (7.6 per cent).

Chart 1: Country comparison: Allocation of household liabilities (%)

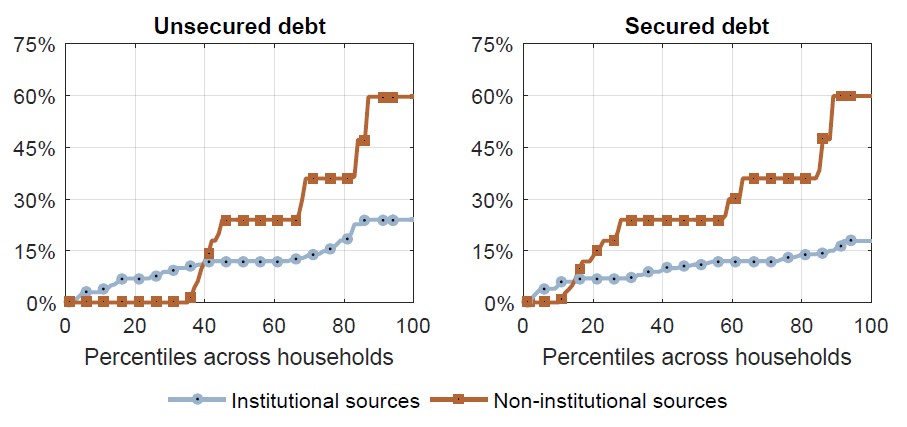

Given the high reliance of households on non-institutional debt, the interest rate paid on such debt (given in Chart 2 below) has grave implications. Most debt from non-institutional sources is at interest rates of 2,3,4,or 5 per cent per month, i.e., 24 to 60 per cent on an annual basis.7 (Interest on loans from family and friends is here assumed to be nil, but, as the HFC remarks, “there is likely significant non-monetary compensation demanded for the provision of such informal credit.”)

Chart 2: Loan interest rates on household debt (% per year)

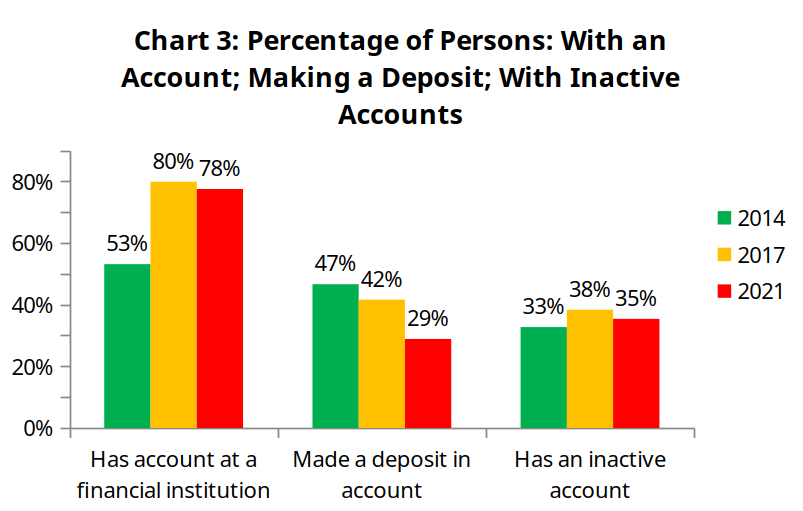

Successive rounds of the World Bank’s Global Findex survey8 – in 2014, 2017, and 2021 – show progress in one respect: the opening of bank accounts. In 2014, 53 per cent of Indian adults (i.e., over the age of 15) had accounts with banks and other financial institutions; by 2021 that figure rose to 77 per cent. Further, the percentage who received their wages solely in cash fell from 79 per cent in 2014 to 43 per cent in 2021. These changes represent what is termed their ‘financial inclusion’.

As is well-known, the Modi government in 2014 directed banks to rapidly open ‘no-frills’ savings accounts for unbanked persons under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) scheme, and by August 2023 it claimed that more than 500 million PMJDY accounts had been opened.9 Despite the fact that PMJDY accounts have been made the channel for Direct Benefit Transfers (DBTs) of various types, the average amount in each account is only about Rs 4,000, compared to an average of roughly Rs 32,000 per savings account for the banking system as a whole.10

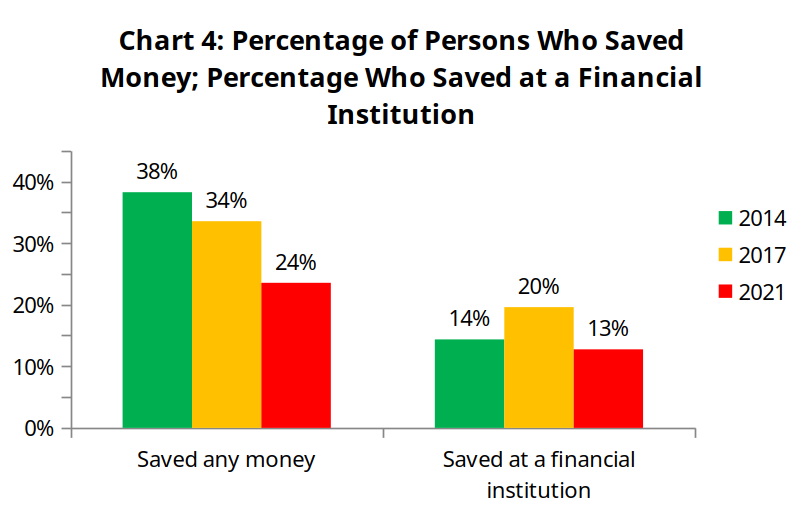

The Findex survey finds that the percentage of persons making deposits in their bank accounts fell from 47 per cent to 29 per cent between 2014 and 2021; and those with inactive accounts rose from 33 per cent to 35 per cent. The percentage saving money in any form fell from 38 per cent to 24 per cent between 2014 and 2021. (See Charts 3 and 4)

Note : Persons 15 years of age or older. Source: World Bank Global Findex 2021.

Note : Persons 15 years of age or older. Source: World Bank Global Findex 2021.

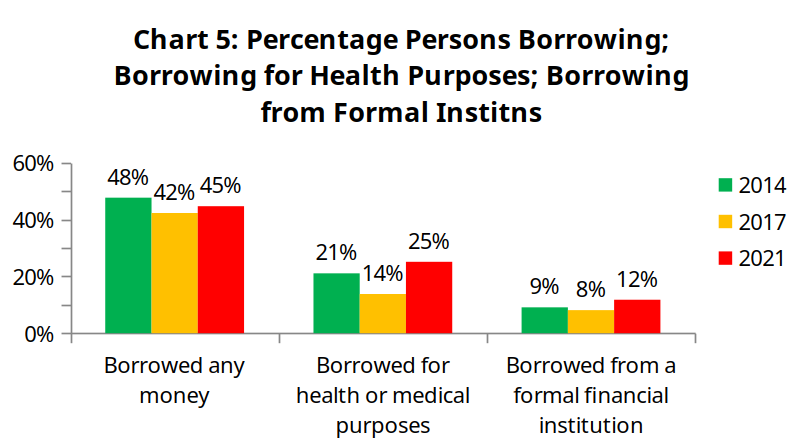

A large proportion, 45 per cent of persons, borrowed money in 2021. However, only 12 per cent of them borrowed from formal financial institutions (such as banks), implying that 33 per cent borrowed from informal sources. Much of this borrowing would be in circumstances of distress: As many as one out of every four adults borrowed for health or medical purposes in 2021. (See Chart 5)

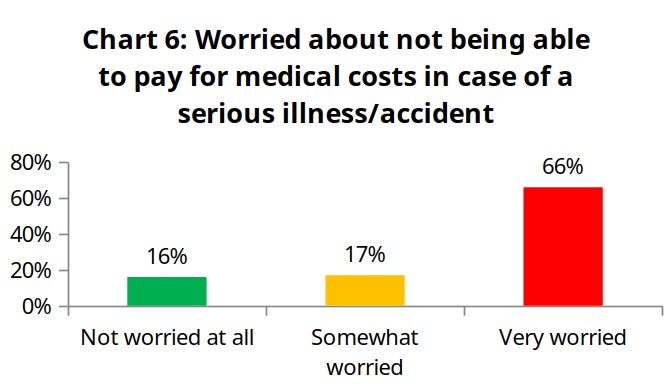

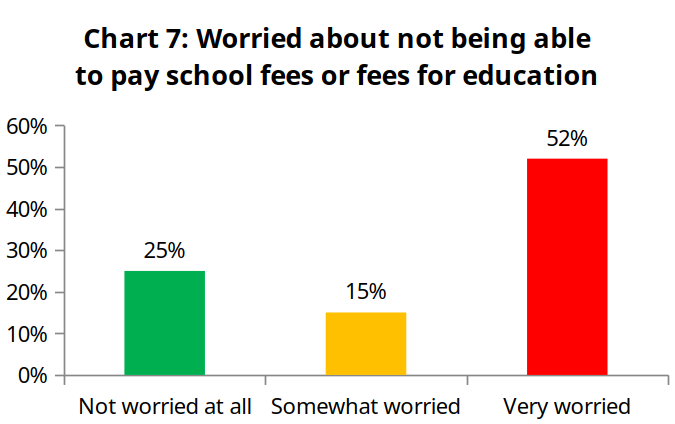

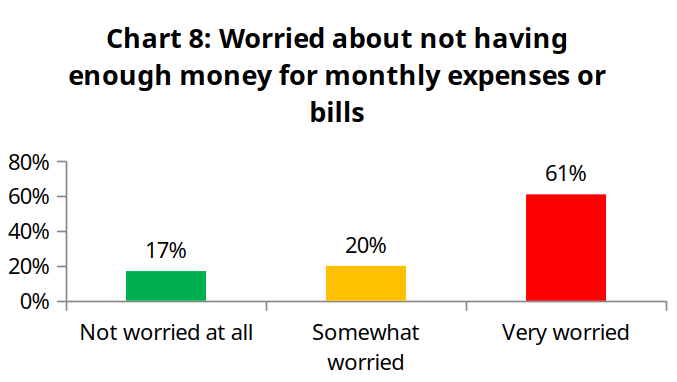

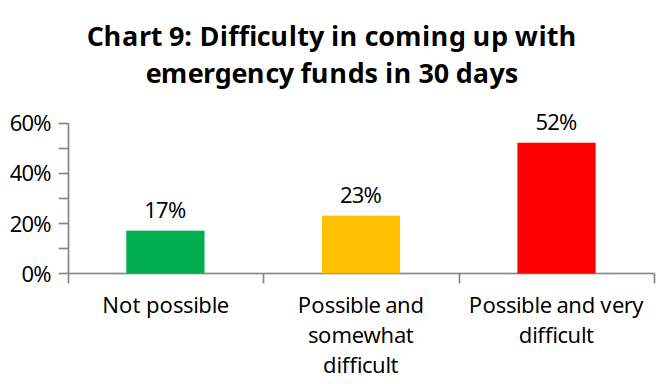

The Findex survey found that most people were very worried about not being able to pay for medical costs in case of a serious illness/accident; not being able to pay education fees; and not having money for monthly expenses. (See Charts 6-8) By implication, their incomes are too low to cover their basic needs, let alone contingencies such as health crises. (The inadequacy of public spending on health and education adds to the burden of these families.) Despite being equipped now with bank accounts, most of them (69 per cent) would find it either impossible or very difficult to come up with emergency funds in 30 days. (See Chart 9)

Not financial creatures

Far from the neoliberal notion of people as financial creatures, the picture that emerges from the above is that most people in India are not voluntarily engaged in financial transactions, especially not for making gains. They are compelled to enter the world of finance in situations of distress, and they do so on adverse terms.

Most Indians are educationally ill-equipped to deal with finance. A nationwide survey by the National Centre for Financial Education (NCFE) found that only 27 per cent of respondents were what it termed ‘financially literate’(24 per cent in the rural areas, and 33 per cent in the urban areas). This was after setting a very low bar for ‘financial literacy’; a slightly more difficult question in the survey, requiring an understanding of compound interest, drew correct responses from only 6 per cent of respondents.11 Similarly, a study done on the basis of National Sample Survey data of 2019 found that 32 per cent of persons were financially ‘illiterate’, 43 per cent had only an ‘elementary’ level of financial literacy, 21 per cent had ‘moderate’ financial literacy, and 4 per cent had ‘advanced’ literacy.12

The process of a digital loan

It is in these circumstances that fintech, and particularly digital lending apps, have entered the market. The steps to obtain a digital loan are as follows:

- A user finds a digital loan app, primarily through online searches and by browsing app stores for related keywords (the most commonly searched keywords are Instant Loan, Personal Loan, Aadhaar Loan, Cash Loan, and Mobile Loan). He/she may also find the app through digital lenders’ marketing SMSs, emails, online advertisements (on websites, social media, apps) and messaging platforms (WhatsApp, Telegram),etc.

- The user then downloads and installs the app from an app store. He/she registers on the lending app using mobile numbers and/or e-mail addresses. The user gives the app the requested permissions. Based on these permissions, the app can access various other apps and services on the user’s phone. In this step, many apps request ‘high-risk’ permissions.

- The user fills the application and thereby provides a host of information about himself/herself. Based on these details, the app pulls the user’s credit score, historical banking information, mobile recharge history, etc. from the phone. Each app uses its own proprietary algorithm to score the user based on his/her ‘creditworthiness’, and decides whether or not to underwrite the loan. (The app provides a guarantee to the non-banking financial company [NBFC] with which it is linked that it will bear the loss of default on the loan.)

- Based on the underwriting, the app displays the loan options for which the user is eligible. The user chooses one of the options. The user then verifies his/her identity and e-signs the loan.

- The loan amount is then credited into the user’s account, either to wallets or, less frequently, to bank accounts. Many of the apps manage the disbursement of cash to borrowers through deemed brokers.

- Based on the repayment plan, the user pays back the interest and principal amount in the agreed number of instalments. In case of delay, firms in the business of collection/recovery step in.13 Their interaction with the user may be either digital or physical.

The entire process would have been impossible without the Government’s programme of building ‘digital public infrastructure’, in the form of Aadhar, bank accounts, the RBI’s Account Aggregator, and so on, which taken together are called the ‘India Stack’. The process is said to be based on ‘consent’: “By allowing consumers to manage all consent agreements in one place, institutions now have access to granular financial data.”14 Given the vulnerability, acute need and lack of financial know-how among the general public, such ‘consent’ may not be informed or truly voluntary.

Sweeping changes afoot?

The activities described above are undertaken by a large number of start-up firms. Of the 14,000 start-ups founded between 2016 and 2021, close to half belonged to the fintech industry.15 In the words of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Working Group on Digital Lending (WGDL), “start-ups and venture capital firms are making a beeline for the digital lending market and in keeping with this trend, 44 per cent of FinTech funding in 2020 went to digital lending start-ups.”16

The RBI think tank CAFRAL informs us that fintech lenders have captured a substantial share of the consumer and retail market; citing an RBI deputy governor, it projects that fintech lending will exceed traditional bank lending by 2030.17 Disbursal through the digital mode has grown more than 12-fold between 2017 and 2020.18 Indeed, the WGDL celebrates the prospect that traditional lending will soon be obsolete:

If past performance is key to predict the future, then it can be unambiguously stated that digital lending is the way to go. In not-so-distant future, lending in general and especially retail and MSME lending through physical mode may be rendered obsolete as is the case with operational banking today…. The FinTech sector can potentially emerge as a substitute for traditional banking in the near future.19

Whether or not this projection materialises remains to be seen; but given the scale of changes the country’s central bank foresees, it is remarkable that it does not feel it necessary to provide comprehensive data on digital lending, or apparently even to collect such data. The RBI’s figure of 12-fold growth, cited above, is on the basis of a sample.

This is in stark contrast to RBI’s practice in relation to “traditional banking”. Here are a few of the statistics the RBI collects and publishes regarding all banks: shareholding pattern; assets and liabilities; non-performing assets (bad loans); off-balance sheet exposure; financial indicators; lending to sensitive sectors (capital markets, real estate, commodities); direct credit for agriculture and allied activities – short and long term; direct finance to farmers according to the size of landholding – short and long term; sectoral deployment of bank credit (agriculture, industry, services, personal loans, and priority sector, with further disaggregations thereof); industry-wise deployment of bank credit; structure of interest rates, occupation wise (agriculture, industry, etc); complaints received; and so on.

In contrast with its admirable thoroughness in relation to banks, the RBI provides us no information on digital lenders. Who owns the digital lenders, and what is the share of resident and non-resident holding? To whom are they lending? For what purposes? What is the size of the loans? At what interest rates? How much is their total lending? What percentage of borrowers default? While private organisations do collect and publish some data in this regard, they are often interested parties and are hardly reliable.20

Near-absence of regulation

The RBI does acknowledge that there are problems in the fintech sector. In the first place, there is a near-absence of regulation, with the majority of digital lending apps “neither regulated nor related/linked to any regulated entity”. Effective deterrence would have required “a multi-agency approach for which any established mechanism was absent. The challenges required agencies to police the boundaries between orthodox financial system and the world of digital lending, practically in a black box.”21 (emphasis added)

The RBI, however, is anxious not to slow the growth of the fintech sector in any way. Hence its basic approach is that the fintech sector should be self-regulated. It released a “Draft Framework for Self-Regulatory Organisation(s) in the FinTech Sector” in January 2024,22 and has also launched a voluntary database, the “FinTech Repository”.23 According to the RBI,

In the context of a new and evolving sector like FinTech, it is the industry participants who possess the deepest understanding of the processes and practices within the trade. Therefore, they are best-suited to establish common rules, enforce them, and effectively handle disputes that may arise from non-compliance with these rules.24

Abuses

Nevertheless, the RBI does note certain widespread abuses:

(1) Noting the high interest rates being charged by DLAs, the WGDL said that “rates of interest beyond a certain level are indeed excessive and can neither be sustainable nor justifiable”.25 Further, there was a lack of transparency in the interest rates, fees and penalties charged.

(2) The WGDL also observed that the use of clients’ data was unregulated, and often illegal.

Several consumer complaints were analysed that cite instances of digital lenders or digital lending apps misusing the high-risk data collected. For example, certain lending apps are collecting users’ entire phone contacts, media, gallery, etc. and using it to harass borrowers and their contacts in case of delays in repayment.26

(3) Finally, the WGDL observed, “the Recovery agents use borrowers’ phone contacts, photos or any other sensitive data to harass borrowers and their friends and family.”27 Nevertheless, the WGDL is reluctant to prohibit the collection of high-risk data: a “prophylactic ban on lending apps accessing certain permissions”, it says, “would adversely impact the growth and innovation in the sector.”28

There are no statistics to accompany these serious observations. How widespread are these practices? What are the average costs of borrowing? How prevalent is the irregular or illegal sharing of data? How widespread is the use of threats, blackmail and coercion in the collection of loans? The WGDL does note the rising number of complaints, but the RBI does not appear to have carried out any survey of borrowers to find the answers to these questions.

On the basis of the WGDL report, the RBI issued “Guidelines on Digital Lending” on September 2, 2022, which stipulated practices for transparent cost and conditions of borrowing, privacy and proper use of data, a grievance redressal mechanism, due diligence by the NBFC regarding the borrower and the digital lending app, a code of conduct for recovery agents, and so on. It mandated that lenders provide a “Key Facts Statement” in a standardised format before the execution of loans.

However, the CAFRAL report of November 2023 showed that all the abuses described in the WGDL of 2021 continue unchecked. (See Box.)

Some Problems in Digital Lending: An RBI Think-Tank’s Observations

The following are remarks from the India Finance Report 2023: Connecting the Last Mile, by the Centre for Advanced Financial Research and Learning (CAFRAL), November 2023.

- While digital lending has taken off, its rapid expansion has raised concerns on issues such as usurious interest rates, unethical recovery practices, data privacy issues, and concentration risk…. Often borrowers are not aware of the total costs of borrowing. Information on the charges and fees are not clearly communicated to them upfront. Interest amounts are not charged as arrears but in advance. There are hidden fees and charges or “teaser” rates that leave the borrowers confused. Money does not always go into the bank account of borrowers, but to third parties.

- A large amount of data is being generated and collected by digital financial companies. These data, if used in an unregulated manner, could compromise consumer safety…. Digital lending can particularly exacerbate these risks as customers share personal and sensitive information over these lending apps…. Credit Information Company (CIC) data have been shared in an unconstrained fashion…. Examples of this include an NBFC sharing information with a Lending Service Providers (LSP) who acts as a customer sourcing partner, or an NBFC sharing information with another NBFC who is not a co-lender.

- Another important concern is the matter of loan recovery process. There are many instances of third parties harassing borrowers regarding the recovery of loans and bothering consumers at odd hours, and by using physical and violent means. Many times, the identity of the recovery agent is not published a priori to the borrowers.29

Usury and ‘inclusion’

In the absence of official data, we are compelled to turn to private surveys, despite the sketchiness of their reports. In 2022, a survey by the social media platform Local Circles found that 14 per cent of the respondents/their family members/their household staff had used instant loan apps in the previous two years. Of these persons, 26 per cent were charged an annual interest rate of between 10 and 25 per cent; 16 per cent were charged 25-50 per cent; 26 per cent were charged 50-100 per cent; 16 per cent were charged “over 200 per cent”; and another 16 per cent “could not say” what the interest rate was. More than half of those who had taken a loan reported a sense of extortion or data misuse during the loan collection process.30

The Fintech Association for Consumer Empowerment (FACE) is a body of fintech lenders, claiming to account for over 50 per cent of the non-bank fintech lending industry. According to a report of FACE, in September 2023 71 fintech NBFCs accounted for 41.5 million outstanding loans, with a value of Rs 55,353 crore, or Rs 13,328 per loan. In terms of volume, fintech NBFCs accounted for over one-third of all personal loans outstanding.31 Unlike most start-ups, digital lenders appear to be profitable, with FACE reporting that 79 of respondent firms were profitable in December 2023.32

According to a news report, FACE reported (on the basis of its members’ self-reporting) that loan processing fees ranged between 1.1 and 5.3 per cent, and the interest rates on loans ranged between 14.5 per cent to 38.3 per cent. The news report makes no mention is made of prior deductions and late fees/penalties, practices that the WGDL found to be prevalent in the industry. Unfortunately, the specific document appears to be inaccessible.33

Importantly, the RBI, as a matter of policy, does not place any ceiling on interest rates, on the argument that high-risk borrowers should be able to obtain loans at high interest rates. “Reserve Bank, as per its extant guidelines, does not generally regulate the rate of interest in a prescriptive manner. Regulators need to tread with caution in quantitatively defining a ‘usurious’ rate as a one-size-fits-all approach would be detrimental to the ecosystem.”34 The RBI ignores the possibility that borrowers in a state of distress may be compelled to pay usurious interest rates. Indeed the existing economic and social conditions provide the basis for the borrowers’ helplessness and the lenders’ usurious terms. In such conditions, private finance will necessarily maximise its profit by taking advantage of the economic and social weakness of the borrowers. If such lending constitutes ‘financial inclusion’, rural usurers have been practising financial inclusion for centuries.

Microfinance as precedent for digital lending

There is a precedent for this model of usurious lending fueled by international finance: microcredit finance institutions (MFIs). With economic liberalisation, the number of rural branches of banks declined in absolute terms by the 2000s, even as urban and metropolitan branches grew. In Andhra Pradesh (AP), the Chandrababu Naidu government, a neoliberal darling of the World Bank, scaled back welfare spending in the rural areas. Instead it promoted ‘Self-Help Groups’ (SHGs) as the agents of rural development.

Banks found it profitable to make loans to the already organised SHGs, resulting in the “realisation that the poor comprise a profitable, albeit an unmapped and nascent, market”.35 Indebtedness levels in AP have for long ranked among the highest in India (the incidence of indebtedness among rural households in AP was 42 per cent in 2002, as compared to 27 per cent all-India36). Sensing an opportunity, by the early 2000s private investors moved into microfinance, and the authorities promoted it as a method of bringing about ‘financial inclusion’ in the unbanked or underbanked rural areas:

However, the increased lending by MFIs often did not lead to any growth in the incomes of the borrowers, since only a small component of this debt was channelled into income generating activities…. [T]he end use of loans from MFIs, most of which went to meet consumption needs. The purpose of these loans were essentially to pay for a) old loans; b) medical care; c) daily needs; d) house repairs, and e) education.37

MFI lenders argued that their costs were high, since they dealt with large numbers of small borrowings in widely dispersed locations; this justified their charging steep interest rates. By this logic, the costs per borrower should have fallen as the number of borrowers increased. But this did not happen; “Rather the increased return on investment was used to grow the volumes even more.”38

The MFIs concentrated heavily in AP, taking advantage of the SHG framework and the existing pattern of high indebtedness. There they grew at a runaway pace: the six leading MFIs increased their lending at a compound annual growth rate of 89 per cent between 2006 and 2010. Between 2008 and 2010, the average borrower’s debt balance toward each MFI more than doubled. By March 2010, statistically, 36 per cent of all households in AP had an MFI loan. At the end of this process, 84 per cent of the indebted households had two or more loans, while 58 per cent even had four or more loans.39 Interestingly, “Traditional moneylenders were not being displaced by MFIs, but rather were thriving thanks to them, effectively becoming part of the business model as moneylender loans were increasingly taken to repay MFIs.”40

Before March 2006, private investment in microfinance in India was a mere $6.3 million; this surged till, between April 2008-July 2010, it received $529 million of investments, “a veritable microfinance investment mania”, as Philip Mader terms it.41 Analysts projected massive growth: one 2007 report estimated total demand for microcredit in India to be $50 billion, at a time when the whole sector was lending only $1.4 billion.42

Indian MFIs were now the blue-eyed boys of global finance. Investors included firms such as Sequoia Capital, a US venture fund which is among the major investors in India’s present ‘start-up’ wave. The six leading Indian MFIs cornered 80 per cent of the investments. The largest MFI, which epitomised the industry, was SKS Microfinance, which enjoyed near-majority ownership by Sequoia, Kismet Capital, Sandstone, and the billionaire Vinod Khosla.43 Investor interest was not difficult to understand: “The sector’s average return on equity (RoE) lay at 27.5% in 2008, and 25.0% in 2009; the largest 10 MFIs meanwhile were even earning on average 37.8% and 35.2%.”44 (emphasis added)

The signs of a social crisis had been evident for years. In 2005-06 itself the AP government was forced to close 50 branches of four MFIs in Krishna district, following allegations of unethical collections, illegal operational practices, high interest rates, and profiteering. “On that occasion,”, according to CGAP (a World Bank ‘financial inclusion’ think tank), “the dispute was calmed by the MFIs agreeing to abide by a Code of Conduct alongside support from the national government and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), which recognized the useful role MFIs played in providing credit for low-income households.”45 The authorities’ approach of ‘self-regulation’ continues today with digital lenders.

The underlying crisis in MFI finance was that the borrowers were poor; they were borrowing for consumption needs; and they could not sustain these rates of extraction. In 2010 their sufferings reached the point of explosion:

In late September and October 2010, accounts of borrowers in Andhra Pradesh committing suicide accumulated alarming reports in local newspapers of rapidly increasing violence. This violence was between borrowers, by MFIs against borrowers, and by borrowers against MFIs. Allegations included instances of kidnapping children and the forced prostitution of young girls to coerce their parents into repayment, as well as abundant reports of MFIs’ agents pressing clients to commit suicide so that life insurances could repay the loans.46 (emphasis in the original)

The Society for the Elimination of Rural Poverty listed 54 suicide cases and the specific MFIs implicated. The entire sequence of events forced the AP government to take action, bringing the industry to a near-halt in the state. The MFI industry tried to shift the blame to ‘fly-by-night’ operators, diverting scrutiny from the activities of the principal firms.

From the Wild West to Big Tech

For sheer abdication of regulation, the present state of digital lending rivals the MFI crisis. Today, according to CAFRAL, “FinTech has widened the range of products available to customers and expanded its distribution channels. Across 80+ application stores…, nearly 1100 lending apps were available for Indian Android users.”47 However, according to the WGDL, 600 of those 1100 loan apps are illegal.48 If the “range of products” offered by fintech is predominantly illegal, the results are unlikely to be good. The country’s central bank appears to have restricted itself to issuing press releases warning the public against such apps.

It is possible that this Wild West phase of digital lending may be succeeded by one in which a few giant firms dominate the field. Firms such as Jio, as well as global tech giants, may enjoy a headstart in such operations. The WGDL notes:

Many large multi-national corporations whose primary business is technology (e-commerce, social media, payments enablers etc.) have started lending either directly or in partnership with regulated financial entities e.g., third-party application providers (TPAPs). These corporations have a captive user base whose data is readily available across multiple business lines and can be effectively utilised in the entire loan management life cycle. These firms have a large-scale customer base and leverage the trust and control generated in this non-financial business for moving into financial services. The firms typically enter the world of finance by providing their data, either raw or processed, to established financial services firms and gradually move towards providing financial services either in partnership or directly to their customers. The size of these entities poses a significant systemic and concentration risk to the economy. They have an unfair competitive advantage over regulated entities [e.g., banks].

The report notes that regulating the fintech activities of Big Tech firms would be particularly challenging, given their complex governance structure; their ability to move funds across subsidiaries and activities; and their ability to cross-subsidise activities across their various businesses. The same might apply to giant Indian firms such as Jio and Airtel. Thus new difficulties of regulating the sector may come to the fore after a reduction in the number of firms.

The development agenda and the question of credit

The proponents of digitalisation might argue that usurious interest rates, predatory lending, and extra-legal methods of ‘loan recovery’ are transient ‘abuses’, which will be corrected through better regulation or through the ‘maturing’ of the industry. However, we need to pay attention to the underlying agenda involved in the shift to digital lending as a form of ‘financial inclusion’.

The post-World War II anti-colonial upsurge and the end of colonial rule in most of Asia and Africa had such profound implications that they affected even the economics profession. (The profession prefers to deal in abstract, static, ahistorical models that justify the status quo.) Economists had to acknowledge that, at least in the ‘developing’ world, it made no sense to treat all economic actors as perfectly informed profit-maximising individuals, equipped with free choice in a competitive market. They allowed that a process of economic development, i.e., not merely ‘growth’, but also structural change, was required. The term ‘development economics’ came into existence. Though it encompassed a wide range of views, it had the concept of change at its core.49

In India, in the wake of repeated peasant upsurges against land alienation under colonial rule, the new native rulers carried out official enquiries into the state of rural credit. The first was the All India Rural Credit Survey of 1954. These reports brought out the stranglehold of moneylenders and landlords in rural credit, which acted as a parasitic form of extraction and an obstacle to development. Moreover, they showed an abysmal paucity of credit to agriculture and to petty producers in general. Despite this, no serious change was brought about in the next decade. It was under the pressure of the deepening agrarian crisis in the mid-1960s, and the upsurge of agrarian unrest from 1967 on, that the rulers in 1969 nationalised 14 major banks. Through the newly nationalised banks, the Government stipulated certain percentages of credit which were to be supplied to hitherto excluded sections, such as agriculture, small-scale industry, and so on. While a sizeable share of credit to these sections continued to come from ‘informal’ sources such as moneylenders, there is no doubt that the new ‘directed’ bank credit had a significant impact in assuaging class contradictions, at least for a while.

In effect, the Government stipulated that bank lending could not be made solely on the commercial judgement of bankers, pursuing profit, as that would reproduce an existing economic condition, which needed to be changed. Even if lending to a section of borrowers yielded less profit, and bore the risk of default (since they were poor, and subject to extreme vicissitudes of nature and volatile markets), such lending was a necessary part of a change in their conditions. Finance was, at least in theory, subjugated to a developmental course. Of course, very limited progress could be made in that direction, since the rulers were not interested to change the underlying social relations which blocked real development. Nevertheless, this period of ‘developmental banking’ mitigated some of the extractions and oppressions by exploitative forces, and gave some boost to the activities of various sections of petty producers.

With the introduction of liberalisation in the 1990s, Government policy towards the banking sector shifted: the direction of bank credit was gradually relaxed, and many bank branches in the rural areas were shut, leading to “the return of the rural moneylender”50 by the 2000s. While the Government took some steps after 2004 to revive the flow of bank credit to agriculture, much of that flow was diverted to powerful borrowers, and there is ample evidence that large numbers of peasants, landless labour, and other rural poor continue to be dependent on ‘informal’ or ‘non-institutional’ lenders.

Now, an even graver change is portended with the Government’s proposed shift to reliance on ‘digital lending’ for ‘financial inclusion’. It is obvious that such lending, by private lenders, would be solely on commercial lines, and not to fulfil any developmental agenda. It inherently will reproduce, or make even more oppressive, the existing conditions of borrowers who are petty producers or labourers – the overwhelming majority in rural India.

Artificial intelligence in ‘credit scoring’

For example, one of the features of digital lending which is celebrated by the World Bank and the RBI as an innovation is the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in ‘credit scoring’. Lenders have traditionally assessed borrowers’ capacity and intention to repay on the basis of standardised information they submit about their ages, incomes, assets, and credit history (loans and repayments/defaults). In recent decades, credit information bureaus provide banks automated ‘credit scores’ of individuals, on the basis of formulas which provide specific weightage to each of the above types of information (different firms use different formulas). Typically, credit scores are three-digit numbers between 300 and 900, and a credit score of 700 or more is considered desirable.

Now firms have emerged which use artificial intelligence (AI) for credit scoring, drawing on new types of big data, including loan applicants’ online browsing behaviour, social media activities, messaging content, telecommunications data, location, network of friends/contacts, and so on. The loan applicant is compelled to dispense with any notion of privacy. “Customers are required to do a social media login since the platform uses the internet presence of customers on social networking sites as a reliable benchmark to assess creditworthiness.”51

Further, the firms may carry out ‘psychometric tests’ on loan applicants as part of the assessment:

One of the more prominent psychometrics providers collects data using tests administered through digital means (SMS), through web-based applications, or through phone interviews to assess a potential borrower’s willingness to pay. The tests assess not only how the applicants answer the actual questions, but how they physically respond, such as how long it takes to answer.52

Drawing on such ‘non-traditional’ data, AI is meant to detect trends and patterns in online activity, and correlate them with the debt-related behaviour of individuals. Once ‘trained’ on such data sets, it is claimed that AI can predict the risk of default by the borrower. (Note that there may be no obvious relationship between the behaviour observed and the prediction of default.) The World Bank describes this as a “disruptive” technology, “disruptive” being the highest term of praise in the fields of technology and finance.

Thus, according to the World Bank, AI credit scoring will advance ‘financial inclusion’:

The biggest opportunity is in enabling greater financial inclusion, particularly for those segments of the borrower population that are consistently marginalized or for whom adequate information is not available…. The introduction of new data sources into credit reporting systems has opened doors for borrowers who did not have formal credit histories or lacked adequate or acceptable forms of collateral to be able to access the credit markets.53

The World Bank argues that AI can use ‘alternative data’ to assess individuals and micro, small and medium enterprises who have little or no credit history (“thin or no credit files”). On the basis of such AI-generated credit scores, lenders can extend loans to persons who would otherwise have been excluded.

Reproduction of existing patterns

First, it is important to be clear about what the application of AI to data sets means. AI is not magic; it is based on an algorithm, that is, a sequence of rules/instructions used to solve a class of problems. AI is of course based on very sophisticated algorithms; it is built to improve its results as it encounters more and more data. Nevertheless, every algorithm is ultimately built by human beings in order to obtain certain results, and hence is the product of specific social circumstances (reflecting the specific social position, attitudes and aims of those building and deploying the algorithm). Any existing social pattern or power structure may tend to get reproduced.

Since the AI itself is owned by a private party, it is not available for analysis by others. Indeed, different firms develop their own softwares, which may produce different results. Further, AI has to be ‘trained’ on particular data sets; depending on the data set used for training, results would differ. As yet there do not appear to be objective studies of the actual performance of different AI technologies in credit scoring; ironically, for lack of data.54 (While the privacy of ordinary people’s data is dispensed with in such processes, the technology which determines their economic fate is kept secret.) Nevertheless, the mystification of data science confers on the output of algorithms the false status of objective truth.

Thus, if the police, due to their prejudices, tend to arrest members of a particular community more frequently, a screening software may pick up this pattern and reproduce it, targeting that community for more intensive monitoring.55 The World Bank admits that

The use of algorithms may make monitoring discriminatory practices trickier because most of these machine learning models are “black boxes,” and thus understanding the way they are reaching decisions or predictions is not clear. Credit scores for consumers from a specific geographical location, race, or gender may be lower, without available explanations from the users of the machine learning algorithms.56

Consequences

All this has obvious consequences in the context of any agenda of development and change. As one study points out, “while a scoring system identifies the factors that are positively or negatively correlated to the ability to repay, it does not analyse the reasons for such a co-relation. Therefore, many characteristics with high predictability may create a disproportionate impact on specific neglected or marginalised classes.”57 (emphasis added)

Indeed, the reasons are crucial. A poor peasant with a small holding, who is vulnerable to the vagaries of nature, and is unable to escape exploitative market and credit systems, may be more liable to default on a loan. Depending on one’s class position, one can draw very different conclusions: either that the poor peasant should be treated as a bad risk and denied a loan; or that the property, market and credit systems that have put the peasant in this situation need to be changed. It is thus not the technology as such, but the class and social position of those who deploy it, that determines the outcome.

We should also note a significant political effect of credit scoring: while peasants at present can agitate to apply pressure on an authority that has denied them their rights, such as a Government office, a bank, an APMC market, or the like, a decision produced by an algorithm makes the location of authority more remote and more difficult to agitate against.

Finally, while the RBI claims that “AI affords an opportunity to serve those individuals who are outside the financial system due to lack of credible credit history”,58 there appears to be no evidence that any lenders have in fact expanded their portfolio of borrowers to such individuals on the basis of AI. One study, using data from an Indian digital lender, argues that AI makes it possible to extend lending to borrowers who would otherwise have been excluded. It calculates that the lender could earn an additional 5 per cent revenue by doing so.59 However, that is very different from evidence of an actual extension of credit by such lenders. At any rate, digital lenders have restricted themselves to short-term consumption loans at steep interest rates, rather than longer-term loans for productive activity. Such is the RBI’s new understanding of ‘financial inclusion.’

The World Bank and the RBI never acknowledge the enormous disparity in power between the lenders and the mass of borrowers, and what this implies. In the present economic order, digital technology merely intensifies this disparity. For example, digital lenders can even use their access to data to target vulnerable borrowers in a purely predatory fashion. A 2021 World Bank study notes that “Unscrupulous actors can use predictions to target individuals likely to produce revenue through late fees or penalties, instead of highly creditworthy individuals.” These practices “disproportionately affect the poorest population segments.” Importantly, “individuals who take on seemingly easy loans but become unable to repay them or are not fully aware of the terms” face “future exclusion from further credit.” The consequences can be severe:

The risk affects a large portion of the population. More than half the individuals who took out mobile loans had a missed payment, according to a recent Consultative Group to Assist the Poor report. And in Tanzania, for example, nonrepayment results in being blacklisted from future credit. Some 20 percent of individuals reported reducing food spending in order to repay mobile loans, in another consequence of inability to repay as anticipated or of borrowing with poor information.60

In conclusion

In practice, AI is deployed in credit scoring, and thus in credit allocation, mainly to help lenders select borrowers, weed out potential defaulters, and charge higher interest rates from borrowers who are assessed to be ‘higher-risk’. Whether or not such AI credit scoring actually ‘works’ (i.e., helps lenders make more profits), is a separate question. What matters is that it firmly and fundamentally installs the principle that the market alone should allocate credit, with the quantity and terms decided by its perception of profitability. The developmental agenda, which had already been watered down over the years, is being explicitly abandoned. Apart from directly promoting corporate lenders, this shift may also indirectly benefit moneylenders, commission agents and traders, who have long been a sizeable source of usurious credit in the rural areas.

- See https://rupe-india.org/aspects-no-81-82/digitalisation-in-india-the-class-agenda/ ↩︎

- S. Ananth and T. Sabri Öncü, “Challenges to Financial Inclusion in India: The Case of Andhra Pradesh”,Centre for Advanced Financial Research and Learning (CAFRAL), 2013. ↩︎

- Cristian Alonso, Tanuj Bhojwani, Emine Hanedar, Dinar Prihardini, Gerardo Una and Kateryna Zhabska Stacking up the Benefits: Lessons from India’s Digital Journey, International Monetary Fund Working Paper, 2023. ↩︎

- Centre for Advanced Financial Research and Learning (CAFRAL), India Finance Report 2023: Connecting the Last Mile, 2023 (hereafter CAFRAL, India Finance Report 2023), p. 60 ↩︎

- Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Report of the Working Group on Digital Lending including Lending through Online Platforms and Mobile Apps, November 18, 2021 (hereafter RBI Report of the Working Group on Digital Lending), p. 54. ↩︎

- Indian Household Finance, Report of the Household Finance Committee (Chairman: Tarun Ramadorai), July 2017. ↩︎

- Ibid. Secured debt includes loans using land or real estate, crops, shares of companies, government securities, insurance policies, bullion or ornaments as collateral. Unsecured debt includes all loans classified as personal security, which are not backed up by any collateral, such as unsecured loans from money lenders, loans fromfamily and friends, and bank credit card or overdraft facilities. ↩︎

- Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, Leora Klapper, Dorothe Singer, and Saniya Ansar, The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19, World Bank, 2022. ↩︎

- Ministry of Finance, “Nine Years of Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana”, Press Information Bureau press release, August 28, 2023. ↩︎

- According to the Ministry of Finance press release (see previous footnote), a total of 50.09 crore PMJDY accounts were opened as of August 9, 2023, with a deposit balance of Rs 2,03,505 crore. According to Resere Bank of India (RBI) data cited by the Business Standard, the average savings account balance was Rs 32,318. Ashli Varghese, “What is the average balance in a bank account in your state? Check it here”, Business Standard, July 19, 2023. ↩︎

- National Centre for Financial Education (NCFE), Financial Literacy and Inclusion in India: Final Report on the Survey Results 2019. ↩︎

- Priyadarshi Dash and Rahul Ranjan, “Financial Literacy across Different States of India: An Empirical Analysis”, Research and Information System for Developing Countries, November 2023. ↩︎

- The above description is drawn from RBI, Report of the Working Group on Digital Lending, p. 56. ↩︎

- CAFRAL, India Finance Report 2023, p. 63. Further, the RBI “has developed a public tech platform for frictionless lending that would facilitate the easy flow of important data to lenders. While the platform itself is not a facility for lending orgranting credit, it aggregates information from various sources enabling lenders to use the information in their lending decisions.” Ibid. ↩︎

- CAFRAL, India Finance Report 2023, p. 60. ↩︎

- RBI, Report of the Working Group on Digital Lending, p. 55. ↩︎

- CAFRAL, India Finance Report 2023, p. 60. ↩︎

- RBI, Report of the Working Group on Digital Lending, p. 24. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 30 and p. 72; italics added. ↩︎

- For example, the Fintech Association for Consumer Empowerment (FACE), which publishes a number of research reports, describes itself as “a self-regulatory industry body of fintech lenders in India. Our growing membership accounts for 80% of digital lending business volumes.” (https://faceofindia.org/about-us/, accessed June 5, 2024) Dvara Research, which collaborates with FACE, is funded by the World Bank, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, WhatsApp, Transunion CIBIL, Axis Bank, and various international financial sector firms and institutions. (https://dvararesearch.com/about-us/funders/, accessed June 5, 2024) ↩︎

- RBI, Report of the Working Group on Digital Lending, p. 38. ↩︎

- https://website.rbi.org.in/web/rbi/-/notifications/draft-framework-for-self-regulatory-organisation-s-in-the-fintech-sector. ↩︎

- https://fintechrepository.rbihub.in/home. ↩︎

- Keynote address delivered by Deputy Governor T Rabi Sankar at the Global Fintech Festival in Mumbai on September 5, 2023. ↩︎

- RBI, Report of the Working Group on Digital Lending, p. 81. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 58. ↩︎

- Ibid. p. 59. ↩︎

- Ibid.,p. 58. ↩︎

- CAFRAL, India Finance Report 2023, 69-70. ↩︎

- “14 per cent citizens said they used loan apps in the last 2 years; most faced very high interest charges, extortion and data misuse”, July 5, 2022. https://www.localcircles.com/a/press/page/instant-loan-apps-survey ↩︎

- FACE, Fintech Personal Loans Apr 18-Sep 23, available at https://faceofindia.org/resource-center/ ↩︎

- FACE, FACETS, Issue 9, December 2023, available at https://faceofindia.org/resource-center/ ↩︎

- Regina Mihindukulasuriya, ‘Like fraud, usurious’ — digital lending apps in spotlight for high interest rates & fees, The Print, December 14, 2022, https://theprint.in/economy/like-fraud-usurious-digital-lending-apps-in-spotlight-for-high-interest-rates-fees/1263975/ The article cites a November 2023 report of FACE, which appears to be unavailable on the website (June 4, 2024). ↩︎

- RBI, Working Group on Digital Lending, p. 82. ↩︎

- S. Ananth and T. Sabri Öncü, op. cit. ↩︎

- National Sample Survey Organisation, Household Assets and Liabilities (as on 30.6.2002), NSS 59th Round. ↩︎

- S. Ananth and T. Sabri Öncü, op. cit. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Philip Mader, Rise and Fall of Microfinance in India: The Andhra Pradesh Crisis in Perspective, Strategic Change: Briefings in Entrepreneurial Finance, 22(1-2), 2013. What follows is drawn almost wholly from Mader’s account. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- CGAP, “Andhra Pradesh: Global Implications of the Crisis in Indian Microfinance”, November 2010. ↩︎

- Mader, op. cit. ↩︎

- CAFRAL, India Finance Report 2023, p. 61. ↩︎

- RBI, Working Group on Digital Lending, p. 27. ↩︎

- We are not here going into the problems with the various theories, or indeed with the term ‘development economics’ itself. ↩︎

- Mihir Shah, Rangu Rao, and P.S. Vijay Shankar, “Rural Credit in 20th Century India: Overview of History and Perspectives”, EPW, April 14, 2007. ↩︎

- Shehnaz Ahmed, “Alternative Credit Scoring – A Double Edged Sword”, Journal of Indian Law and Society, Winter 2020. ↩︎

- World Bank, Disruptive Technologies in the Credit Information Sharing Industry: Developments and Implications, 2019, p. 22. ↩︎

- World Bank, Disruptive Technologies, p. 13. ↩︎

- A World Bank study notes: “To date, there is little evidence on the ability of digital credit scoring methods to predict default risk.” — Kateryna Schroeder, Julian Lampietti, and Ghada Elabed, What’s Cooking: Digital Transformation of the Agrifood System, World Bank, 2021, p. 110. ↩︎

- Will Douglas Heaven, “Predictive policing algorithms are racist. They need to be dismantled.” MIT Technology Review, July 17, 2020. https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/07/17/1005396/predictive-policing-algorithms-racist-dismantled-machine-learning-bias-criminal-justice/ ↩︎

- World Bank, Disruptive Technologies, p. 13. ↩︎

- Shehnaz Ahmed, op. cit. Similarly, 2021 World Bank study acknowledges that the ability of digital credit scoring “to accurately predict the creditworthiness of marginalized populations is questionable. There is some criticism that the ability of digital credit scoring to predict creditworthiness is weak, leaving both risk and interest rates high.” — Schroeder et al., p. 114. ↩︎

- RBI, Working Group, p. 23. ↩︎

- Sumit Agarwal, Shashwat Alok, Pulak Ghosh, and Sudip Gupta, “Financial Inclusion and Alternate CreditScoring: Role of Big Data and Machine Learning in Fintech”, April 2023. The data are of short-term loans, for 15-180 days, at a monthly interest rate of 1.75 per cent. ↩︎

- Schroeder et al., p. 115. ↩︎