The Real Issues Underlying the Ever-Deepening Crisis of BSNL and Other Public Sector Units

In Aspects no. 80 we followed the story of the development of the mobile telecom services sector in India since the entry of private firms around 30 years ago. We... Read more.

Making Sense of the Present Moment of ‘Onlinisation’ of Teaching

If education is more than merely offering ‘content’, online education is very far from a serious teacher’s idea of reasonable education. Among other things,... Read more.

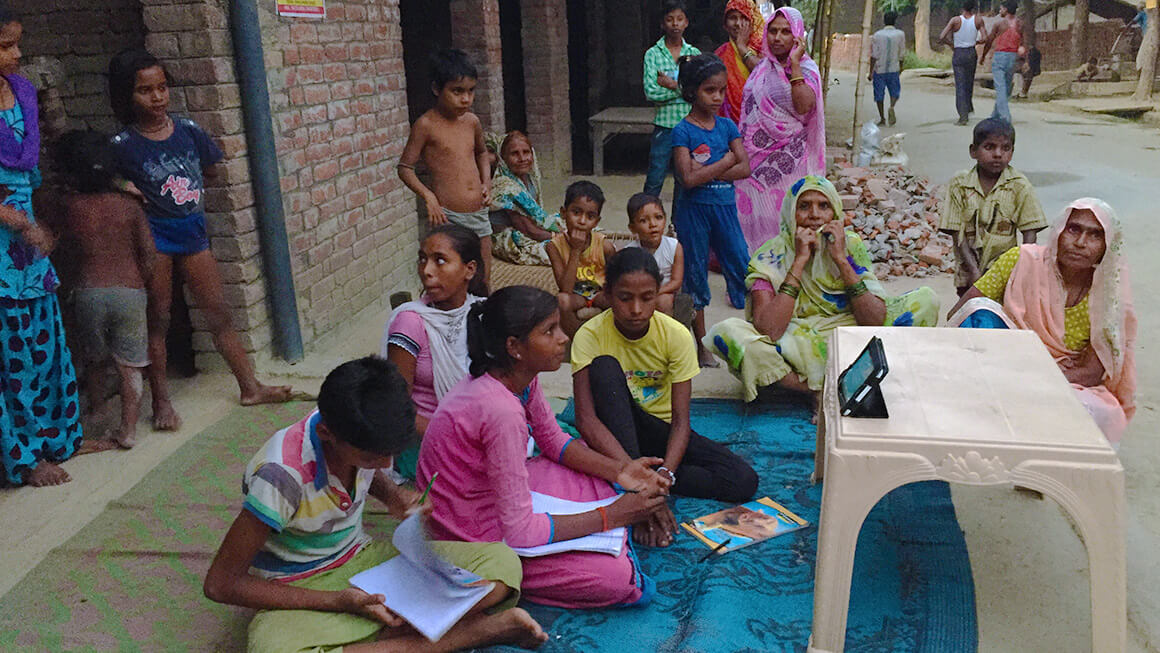

Digitalisation of Education: A Dystopian Solution for a Dismal Reality

After almost eight decades since independence, the state of India’s school education remains in complete disarray. Though a significant number of children of school-going... Read more.

Indian Telecom’s Spectacular Rise and the Nature of Monopoly Capital in India

Votaries of the prevailing policies extol India’s private corporate sector for spreading mobile telephony widely, at low prices. This article looks behind this... Read more.