Preamble

The world is ‘digitising’ and ‘automating’ furiously, and this process is underway in India too. This process is marked by the ever-increasing deployment of robotic machines and complex software systems – now driven more and more by Artificial Intelligence (AI) – across different sectors of the economy.

— In the advanced countries, and increasingly in leading firms in India, machines may be used to carry out almost the whole range of manufacturing operations with only a handful of humans.

— Financial transactions are now ubiquitously made and tracked through software.

— Office work is heavily dependent upon computers, the cloud1, all kinds of software and now intelligent bots. A significant amount of office work can be accomplished virtually, from home or any other part of the world.

— Everyday life requires the use of computers, mobile phones and apps to access services such as banking, shopping, traveling, and messaging. Documents – certificates, receipts, IDs, newspapers and even books – are becoming ‘dematerialised’ – from paper to soft versions stored on computers or mobile phones, or somewhere on the ‘cloud’.

The internet serves as the backbone to which many of these systems are attached. Much business, work and leisure is now conducted on platforms hosted on the internet.

Ground reality

With such ‘revolutionary’ technologies becoming commonplace, one might expect a more just, fair and equal world, given the dominant discourse that ‘digital’ provides for greater efficiencies, opportunities and ‘democratisation’ (1, 2). However, the last decade of increasing digitisation in India has also been a period of growing poverty. This was evidenced by the 2017-18 Household Consumption Expenditure survey, which the Government scrapped due the unflattering picture it revealed.2 The full data of the latest such survey, of 2022-23, have not been released as yet.

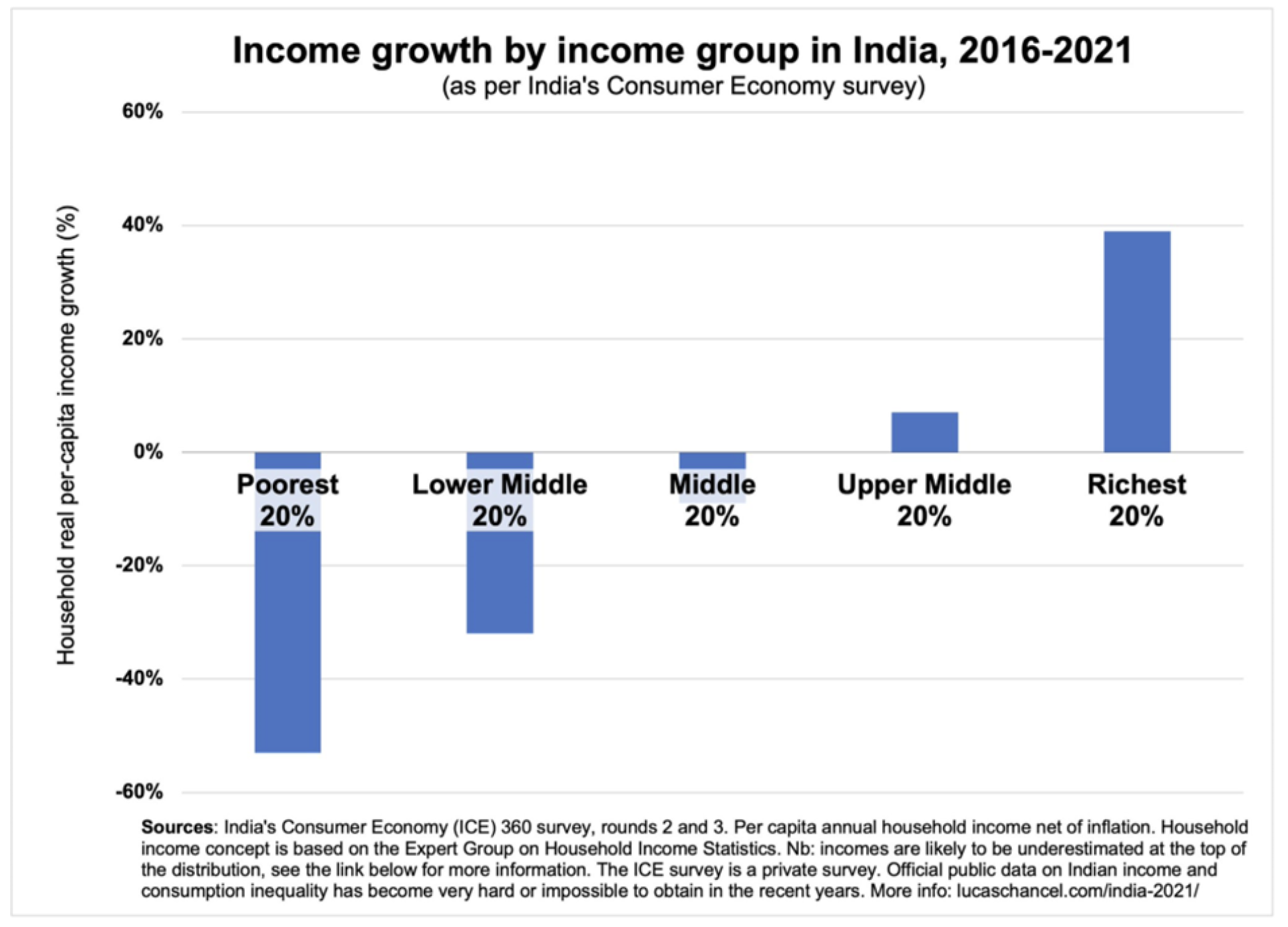

A private survey of income growth during 2016-21 found a dramatic widening of inequality (see chart below). Although this reflects, in part, the effect of the Covid lockdown, the ‘scars’ of the lockdown would have lingered since.

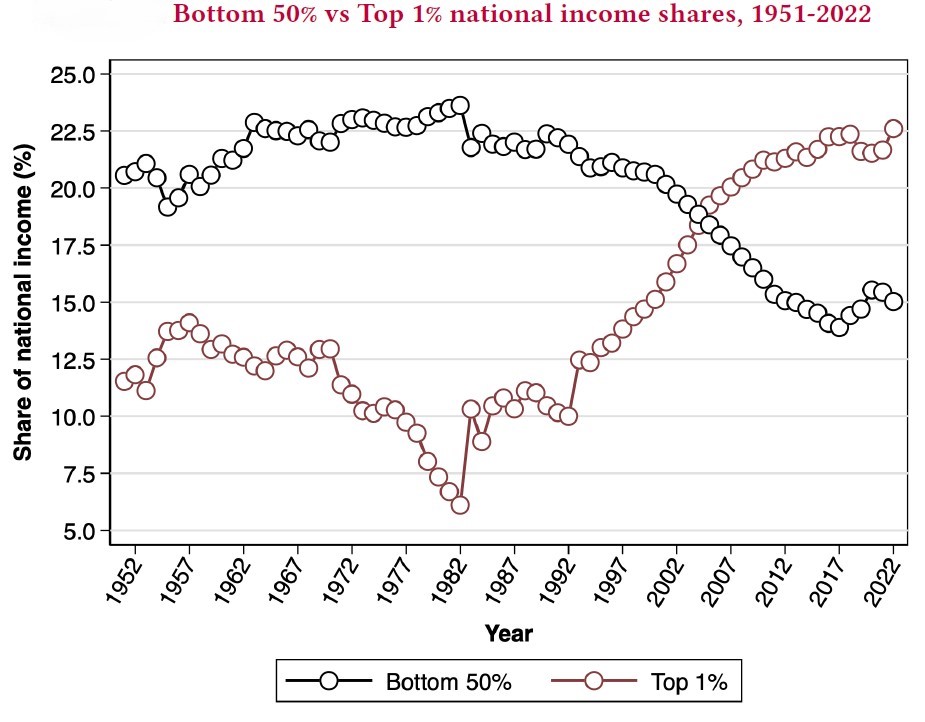

An important new study, drawing on a range of data sets, finds income inequality in India increasing since 1991, skyrocketing in the 2000s, flattening marginally during the growth slowdown of 2017-20, and sharpening once more with the recovery since 2021. Present levels of inequality, the authors conclude, are greater than under the British raj: “By 2022-23, top 1% income and wealth shares are at their highest historical levels at 22.6% and 40.1% respectively and India’s top 1% income share is among the very highest in the world, higher than even South Africa, Brazil and US.”

The working class now includes an influx of delivery ‘boys’, drivers, ‘handymen’, and househelp hired through online platforms for performing specific jobs. The most visible are the people who deliver online shopping merchandise and food from restaurants, as well as the drivers of cab hailing companies. Their condition can be described as ‘precarity’: their living conditions are precarious, their incomes are unstable and social security of any kind is unavailable to them. This is the much vaunted gig or platform economy.

One must remember of course that India has always had a large conventional informal economy where people engage in work on a gig or short-contract basis, such as in construction and agriculture. In this article we refer to the gig economy as comprised of the new ‘digital’ platform workers.

In another sphere of daily life, online access has made shopping or banking more convenient for the better-off; but for many more, ’online’ is a labyrinth they find difficulty in navigating. Various kinds of identity and address documents are required for many routine activities, such as opening a bank account, buying a SIM card and accessing the public distribution (ration) system. Most of these require online authentication (fingerprints, iris scans) or scanning of documents. The most well known, or notorious, is the Aadhar ID issued by the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI).

Digital divide

With the Union government’s growing penchant for “keeping track of everything3, even more systems are switching to digital modes using the Aadhar authentication system such as for social security schemes involving direct bank transfers, healthcare access, creating land records databases, and so on. All of these systems and schemes require the use of computers or smartphones to work. Those who do not have smartphones or do not have sufficient digital skills required are excluded from this ‘digital life’; some manage by taking assistance from friends, family or agents.

The impact of this ‘digital divide’ was starkly evident during the Covid-19 pandemic. Students from poor families had great difficulty in accessing online classes because of lack of adequate digital resources – laptops, mobile phones, data packs and even electricity. Similarly, the almost exclusive focus on the CoWIN app as the gateway for accessing Covid vaccination appointments proved to be a barrier to people who had no means or the knowledge to use the app.

An even bigger problem is the failure of the digital services infrastructure in areas which serve the poorest and socio-economically the most vulnerable. Such failure results in the denial of service to those who need it most. The best known examples of this are when foodgrains provisioned for the poor, and to be delivered through the PDS system, are denied to them because the fingerprint reader does not work or internet connectivity is poor. This foodgrain which is not delivered is then shown as ‘savings’, and used to create a narrative of having ‘weeded out fake users’ specifically because of the ‘accuracy’ and ’effectiveness’ of digitalisation of the entire process.

It is not only the gaps or failures that pose a risk: The presence of inherent ‘design’ flaws (1, 2) in the technologies themselves too carry dangers, as, for example, when biometrics misidentify an individual s/he can be denied a service or be falsely accused of a crime (1, 2, 3, 4).

Technological ‘disruption’

Historically, new technologies create ‘disruption’ in two major ways.

First, technologies change the nature of work itself.

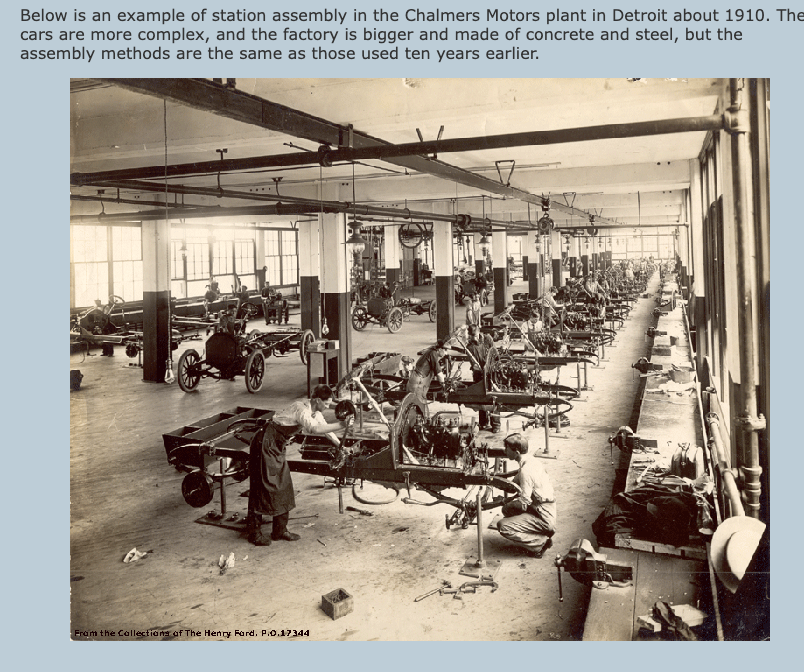

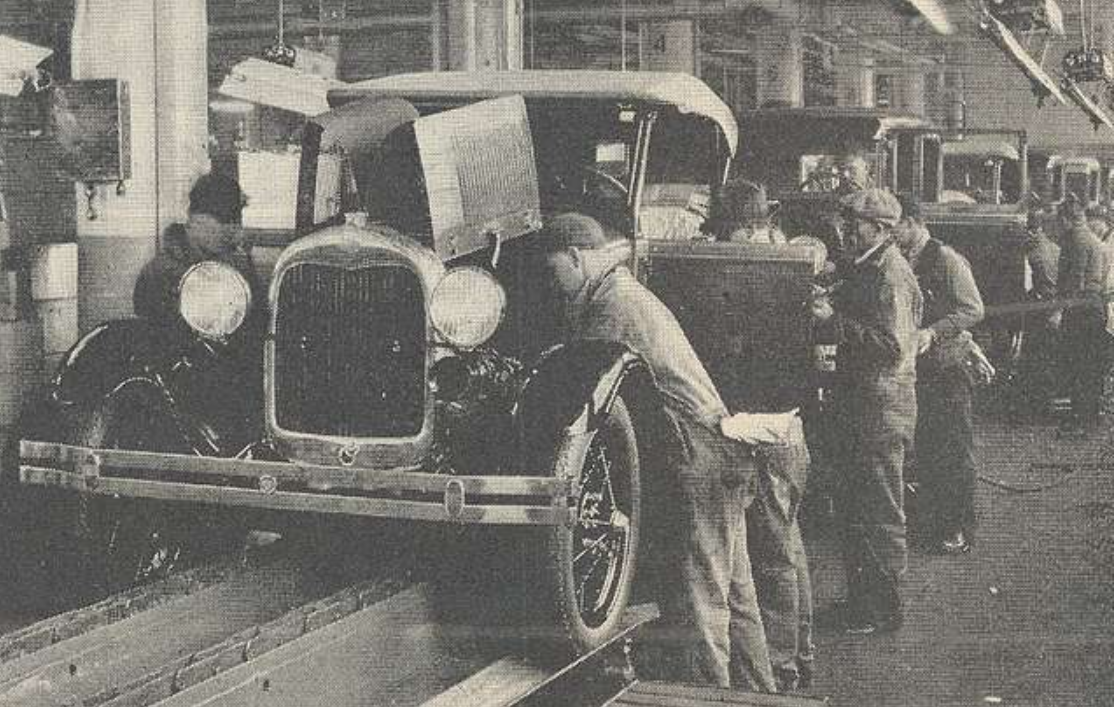

The history of capitalism is the history of technology that has been adopted to increase the productivity of labor, cheapen wages, and acquire greater control over the labour process by displacing troublesome and ‘insubordinate’, thinking human labor. Consider the evolving car manufacturing scenarios: (1) a few mechanics/craftsmen putting together a whole car; (2) the Fordist assembly line, where each worker performed the same operation repeatedly and (3) the modern car-making factory, where a few workers supervise an assembly line being worked upon by robotic machines. For each successive scenario the number of workers needed to produce a certain number of vehicles has decreased.

The advent of computers made machines more sophisticated (computer-controlled, programmable). It also transformed office and clerical work. Word processors, scanners, and printers enabled the dematerialisation of documents, and affected office organisation (storage, retrieval). Computer networks enabled collaborative sharing of work and rapid communication (email, messaging apps). The arrival of the internet has given rise to platform capitalism where workers and ‘employers’ interact on platforms hosted on the internet, for ‘gig work’. If automation affected blue collar workers in the manufacturing sectors, the latest disruptions, featuring AI, now threaten to affect white collar workers as well, because mental work is being taken over by AI technologies.

Labour replacement thus leads to precarity for the many who are replaced. A few retrain and find newer jobs, most are pushed into the informal sector where employment is intermittent, and without any social security or benefits that accrue to tenured or regular employees.

Second, technologies alter culture and politics directly through their adoption and spread. For instance, communication technologies changed the way we interact with family, friends, community and the government. The printing press made mass reading possible and altered the way in political canvassing was conducted; the telegraph, phone and television changed communities from being focused only on local happenings to developing an interest in far flung regions across the world; the internet has paved the way to newer and more rapid forms of commerce and consumption, and social media have provided platforms that have not only changed the way we conduct interpersonal interactions but have also been used by governments to surveil and control their own citizens.

It is inherent to these transformations that those who do not have access to the new technologies face varieties of social, economic and political exclusions.

Technology (the ‘means of production’) and labour replacement

The replacement of workers by machines is vividly illustrated by the effect of deployment of mechanical devices in the spinning and weaving industries. The use of the spinning jenny and the water frame in the second half of the 18th century, and, later, powerlooms driven by steam or water power, made it possible for a few workers to do what required many more when these devices were not available. Mass layoffs and closure of handloom workshops left many workers unemployed, many of whom struggled to find other jobs which needed a different set of skills.

In the early part of the 20th century, the adoption of the assembly line in the manufacture of cars caused similar waves of unemployment. In the pre-assembly line era it took about 12 hours to build a Model T Ford car. In the assembly line mode the production time dropped to 90 minutes, and Ford halved his workforce within a year. In the older form of production, skilled machinists, blacksmiths, and woodworkers made up the majority of workers at Ford, and these jobs required years of training and apprenticeship. When the assembly line came into being, many of these skilled workers were replaced by semi-skilled ones whose only task was to perform repetitive actions on specialised benches of the line. From 1910 to 1920 the percentage of unskilled workers in Ford car factories transitioned from only 10 per cent to 70 per cent. Even though the total number of employees rose because of an expanding car market, their wages dropped significantly.

More recently, starting in the late 1980s, robots began to be deployed in car factories. Yet again this led to huge numbers of jobs being lost, and estimates suggest that robots have replaced more than a million jobs in the period 1990 to 2016. Now, AI-enabled robots which have the ability to ‘learn’ and adapt are coming in, and more job losses can be expected.

Technological unemployment

John Maynard Keynes was the first to use the term ‘technological unemployment’ to describe labour replacement because of the deployment of new technologies. While it is obvious that in the short term, after technological change, there is a spurt in people becoming redundant, the long term impact is neither clear nor unique.

There is a controversial yet dominant belief that expanding economies and the newer jobs resulting from the newer technologies have always managed to compensate for lost jobs. While it is true that we have not yet seen a comprehensive, catastrophic collapse of capitalist economies, this hypothesis is hard to validate, given its deep complexity and the lack of historical employment data that needs to be evaluated in this context. Yet, the idea prevails and the flippant ‘proof’ offered is that capitalism as a socio-economic system is the only one that is alive and kicking; the belief has now become inherited wisdom. If one considers that the capitalist economic expansion has also been marked by a corresponding growth in population, an ever greater concentration of wealth by the rich, the establishment of colonies, and the formation of large informal economies (e.g. the early servant economy, and now the new servant economy aka the gig economy) – providing only refuge employment or underemployment under exploitative conditions – it suggests that the belief in the complete reabsorption of displaced labour is somewhat simplistic.

State of employment

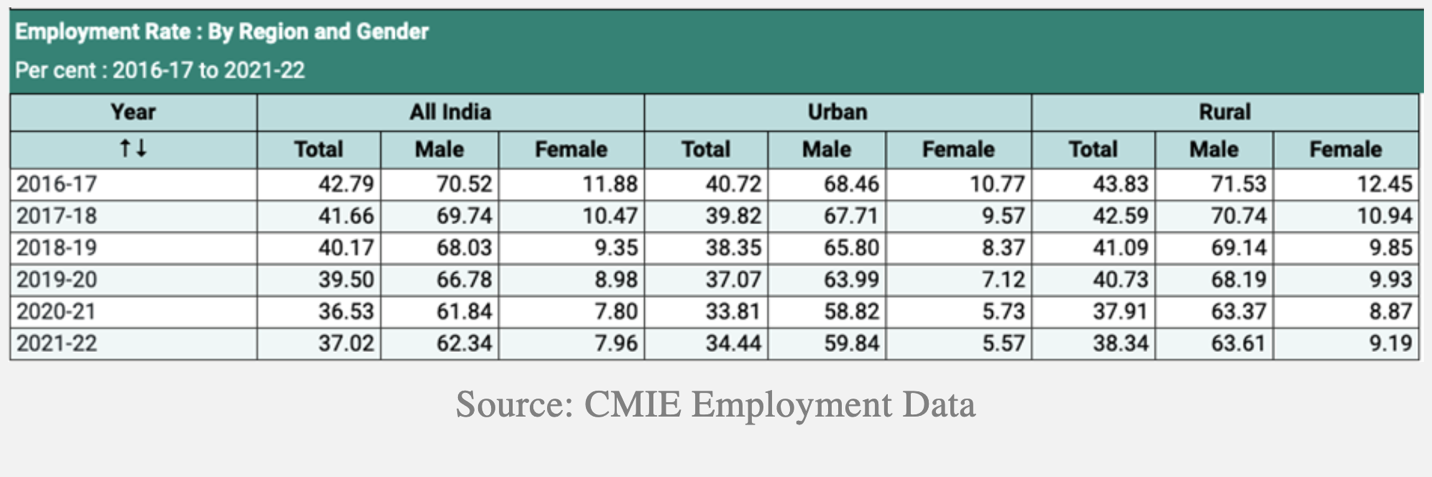

The state of employment in India continues to be dismal, and worsening. The table below shows that the percentage of population employed, which was already low by global standards in 2016-17, has fallen sharply since. And this is seen in both men and women, urban and rural workers.

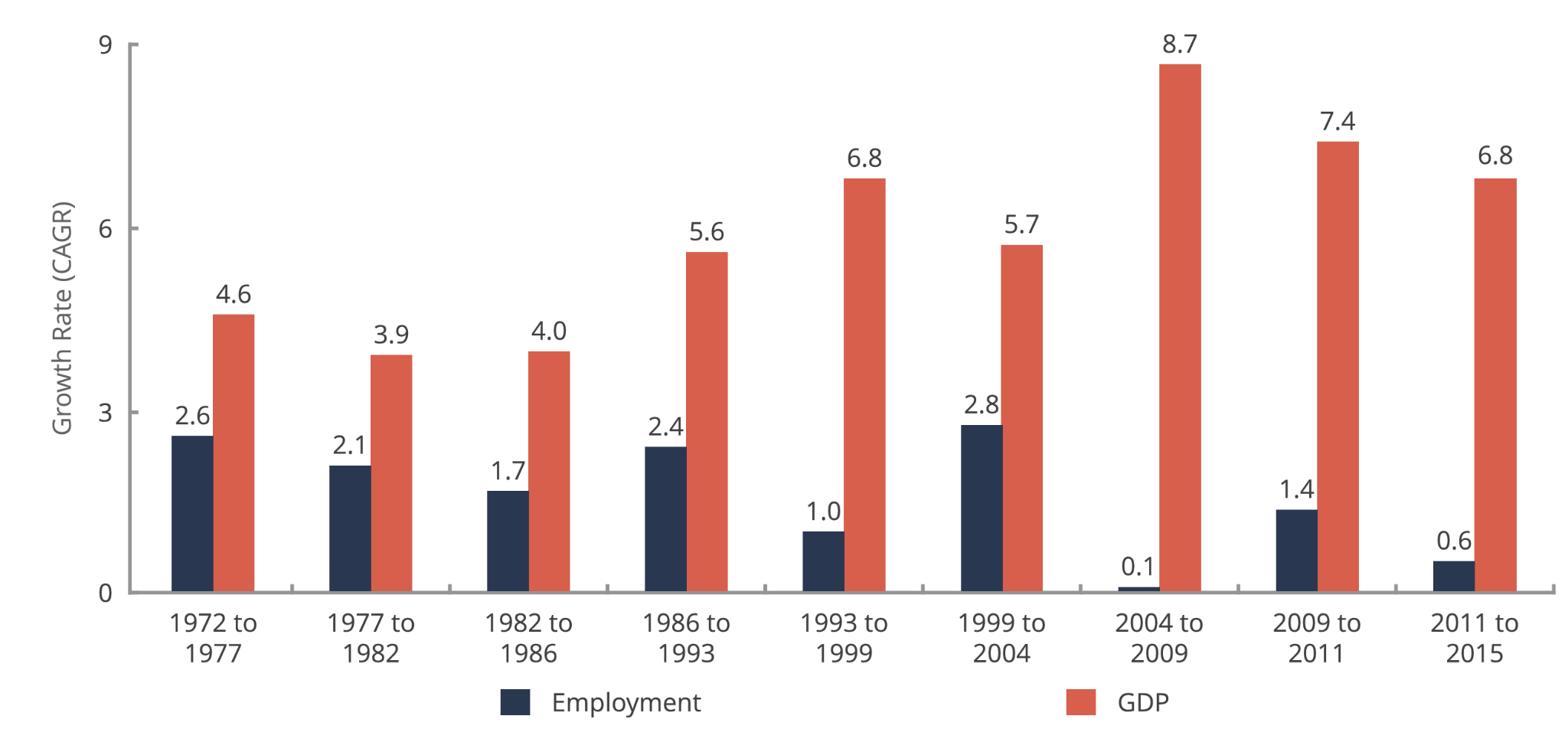

Jobless growth is best represented by the growing disjunction between the Growth Domestic Product (GDP) and employment. The graphic below shows clearly that even as GDP has grown, employment has not grown that much, and the difference has worsened with time, particularly since the post-1991 economic policies. This disjunction between growth of GDP and employment largely predates digitalisation, but it is likely to become even sharper as digitalisation proceeds.

Labour fragmentation and the nature of ‘gigs’

Taylor’s “principles of scientific management” laid the foundations of the fragmentation of work, or labour processes, more precisely. Essentially, the full process of manufacturing an object (e.g. a car) was broken down into simpler tasks which were optimised for speed (e.g. turn a screw 2 rounds – takes 30 seconds, hammer 3 times – takes 15 seconds, and so on), and each of these simple tasks was allotted to a single individual to repeat endlessly, and the partially ready object then passed on to the next person who performed the next simple task. These ‘time and motion’ studies provided the basis of the assembly line in manufacture. The primary effects of this fragmentation at the time of its early deployment were the huge increases in productivity and the alienation of the worker from his/her craft; along with it came the replacement of the skilled craftsmen by fewer semi-skilled workers, and the drudgery of monotonous, repeated, uncreative ‘actions’.

Fragmented labour processes have also enabled many other arrangements of working. As corporations went global in their hunt for cheap(er) labor, outsourcing of select fragments of the manufacturing process to these, often overseas, locations (e.g. China) became common. Beyond manufacturing, (back) office work also became outsourced (e.g. call offices in India). Robotic automation could handle even more finely fragmented tasks with greater precision and speed.

Internet-based platforms, powered by varieties of digital technologies including AI, now enable nearly instant outsourcing of tasks to the lowest bidder. A platform like Mechanical Turk is used to assign tasks such as data entry, image tagging, coding, editing, writing and much more to those who will carry them out on a ‘per piece’ basis for the lowest payment. Such work entails no long term commitment and no benefits to be given to the “worker” doing the assigned task.

We have entered a phase of ‘work’ where more and more employment is being ‘gigified’, which is the contemporary label for ‘informalisation’. The result is the destruction of regular or tenured employment that comes with benefits, security and union support, and its transformation into ‘employment’ which is precarious and without any kind of security.

This ‘class’ of working people is termed the precariat4 – a proletariat (the working class) under even more uncertain conditions than it was till now. Moreover, members of the precariat undergo periods of unemployment when they are waiting for the next gig. They do not have access to employer-subsidised housing and health insurance, paid vacations, unemployment benefits, pensions, provident funds. Therefore, they must access housing or health insurance from the market. Often an illness or accident can lead to a shock spiraling into indebtedness and poverty. Workers in the gig economy lack an occupational identity and have to switch jobs, such as working as a driver on one day and a security guard on another. They must also retrain continuously for different types of work, mostly using their own resources, and yet suffer from low social mobility. Much of this may seem familiar in the Indian economy, which has always had a huge informal sector. The only difference is that now it is being filled up ever more rapidly with people losing regular employment or never finding one.

A recent CIEL survey reveals that more and more industries in India are planning to employ gig workers rather than regular ones. The survey report enthusiastically suggests that gig work is becoming popular because of the usual hyped reasons (extra income, exposure to different projects, own boss and making free time). Perhaps this applies to the upper-end professionals who work on projects (rather than deliver food or drive cabs). The survey also shows that gig workers are concerned about the uncertain nature of work, lack of social security, unstable income and limited job growth. Many IT firms have turned to gig workers rather than regular hires. An earlier NITI Aayog report claims that the gig workforce is expected to increase from a current value of about 8 million (in 2022) to around 23.5 million by 2030 (these figures ostensibly refer to non-platform plus platform gig workers).

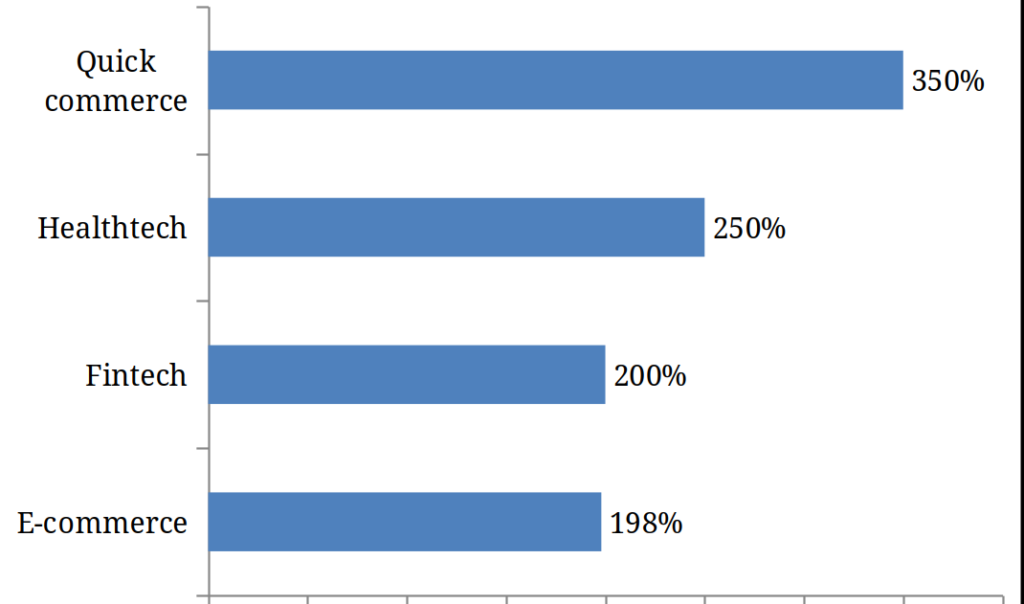

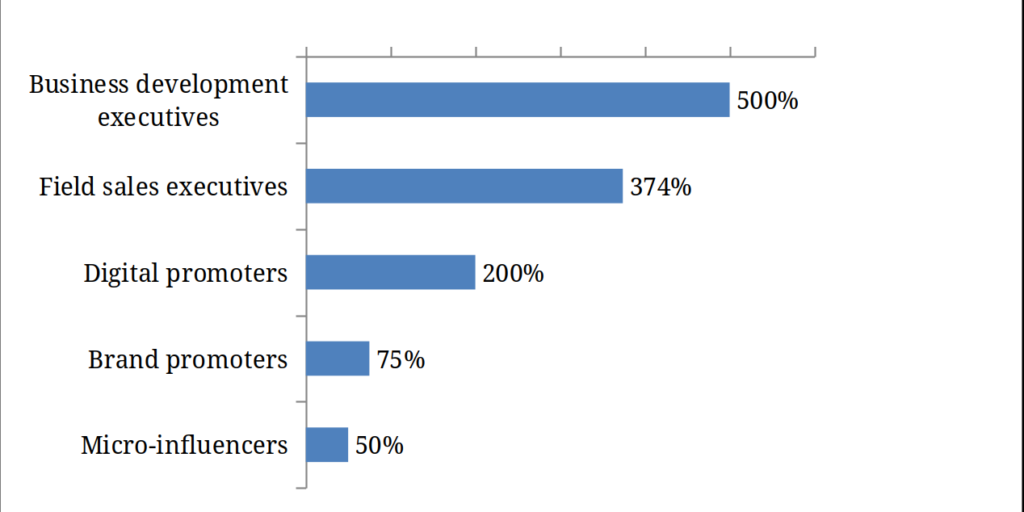

We can see the direction in which this is going. The rise in ‘demand’ for gig workers – i.e., employers’ demand for workers without any obligation to continue hiring them — is huge across all sectors.

Source for above two charts: Soumyashis Bhattacharya, “India Inc increasingly need gig workers, looks at Tier-2,3 cities: Report”, Business Today, June 15, 2022, citing data from Taskmo Gig Index.

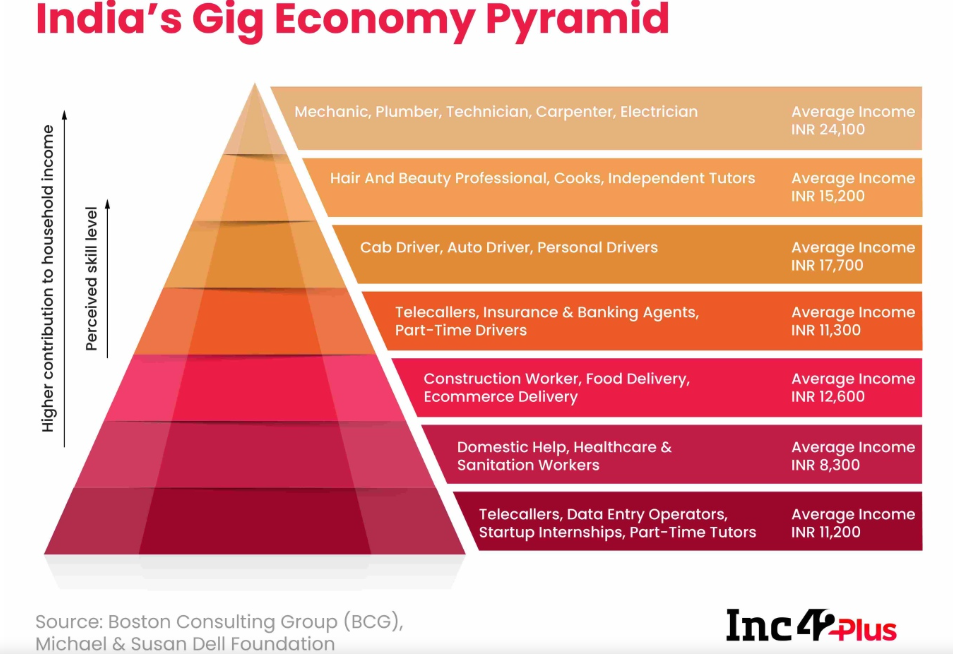

A more detailed view of the “Gig Economy Pyramid”, which includes the kind of work and the average monthly income, is shown below.

The lives of gig workers

A variety of news reports (1, 2) describe this life. Uber drivers are typically trapped by the loans which they took to buy the vehicles they drive. They have to continue driving to repay the loans under exploitative conditions. Drivers claim that roughly 25 to 30 per cent of their earnings are taken away by Uber, and that there are hardly any savings at the end of the day. Uber enticed people initially by hype centered on the great earnings drivers would have, and by projecting that they would be bosses of their own time, but once it drew in or captured a large fleet of cars and drivers, drivers’ real earnings have dropped. Rising fuel costs, demonetisation and the pandemic have eaten into the decline of earnings that can be had through app-based cab services. For women drivers the situation is even more terrible, with issues ranging from lack of washrooms to fear of assault. A similar situation haunts cab hailing drivers everywhere.

Meanwhile, the lives of regular taxi drivers has been upended in many ways by the entry of Uber and Ola.

Delivery workers fare no better. A never-ending day with dwindling incentives and horrible traffic is what most delivery ‘partners’ face in order to earn around Rs 25,000 per month, perhaps even lower, as another detailed study suggests .

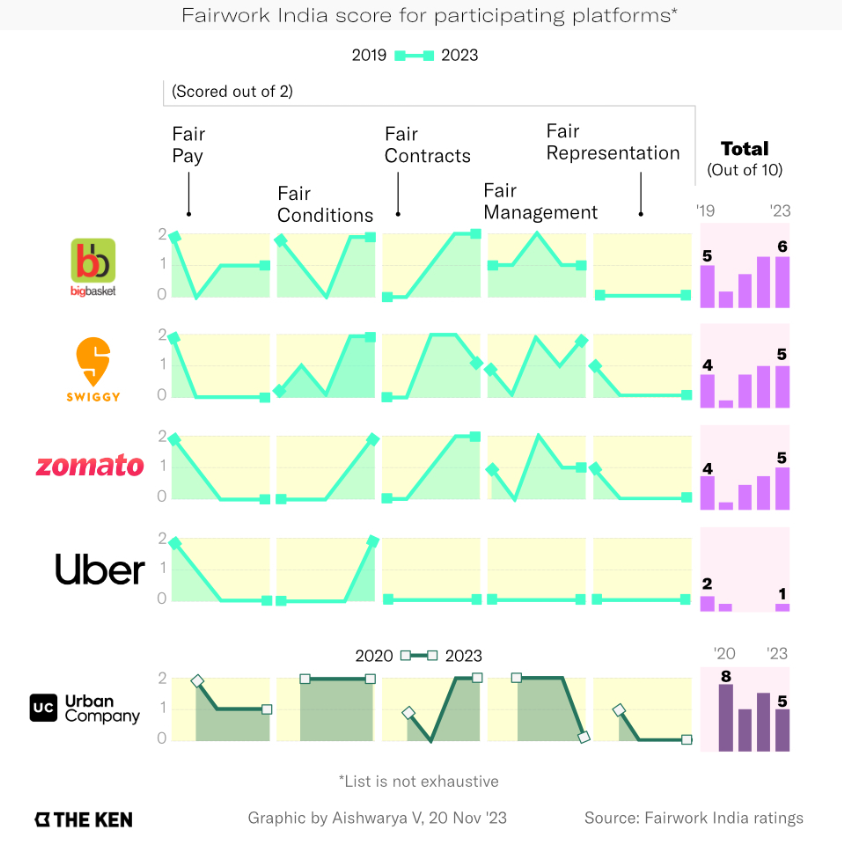

Fairwork India – an agency that rates platform companies in terms of fair pay, conditions, contracts, management and representation – concluded in its report of October 2023 that while a few companies paid minimum local wages to its workers, none of them paid a decent living wage. No company gave fair representation to their workers. The Ken’s analysis of the report is instructive. Their graphics summarise the situation neatly.

Gig workers and labour laws

The fundamental problem is the classification of gig workers as partners or independent contractors and not as employees. This denies them benefits that are rightfully due to workers under conventional labour laws. This issue has been alive ever since the advent of the gig economy, and legal disputes in this matter have led to a variety of judgements. The Biden administration’s latest rules, which will ensure many gig workers are counted as employees, and the reactions to this move, show that the battle is still in progress. Many American states have their own laws regarding gig workers, some of which are seeing protracted legal challenges. The UK has seen some victories of gig workers in court rulings: the The UK Supreme Court ruled in 2021 that Uber drivers should be treated as employees rather than as self-employed partners. The Platform Work Directive from the European Union seeks to improve the condition of gig workers in Europe. These directives deal not only with classification of gig workers, but also put in place rules that will govern how algorithms manage and monitor gig workers, and what kind of data privacy will be accorded to these workers.

In India, the Code on Social Security (2020) provides for an e-Shram portal where gig workers can register. The idea is to create a national database of unorganised sector workers. The Code envisages framing of social security schemes for gig workers covering life and disability benefits, health insurance cover and so on. A social security fund is proposed, and this will be funded by contributions from aggregator platforms. The operationalisation of this Code is stalled because the states need to publish rules for its implementation, and the talks between the Union government and labour unions are inconclusive. This Code has been critiqued severely for major anomalies and shortcomings. The framework is quite complex and cluttered, with multiple authorities; there is no dovetailing of these to existing social security schemes; and most significantly, there is no indication of where the funds will come from for financing these new social security rules.

Even though one speaks of the ‘gig economy’ as a concept, there is variety in terms of the way work is organised. For instance, there are platform workers such as drivers and delivery workers, who deal with the platforms on the one hand and customers on the other; on the other hand there are contract workers such as warehouse workers or back office staff, who do not interface with customers. Finally, there is gig work that is not aggregated through a platform but given directly by a client to a gig worker. While some rights that gig workers seek are universal, such as access to healthcare or social security, the remedies to other issues are likely to be more specific, such as demands relating to working conditions (which differ for, say, drivers and warehouse workers).

This confusion can be seen in laws being made in a somewhat hurried manner. The Rajasthan law on gig workers is a classic case. While the law is pioneering in that at least a state government has woken up to the fact that gig workers need legal rights and protections, the law seems quite inadequate and not sufficiently fleshed out. The essential structure of this law is through the establishment of a welfare board – with members of the company, worker representatives and the government – which will register platform-based gig workers and then bring out, as well as administer, social security schemes for them. It proposes that a cess be collected from each bill paid by a customer, which will be credited to a welfare fund. The board will also serve as the agency that redresses grievances of the gig workers. However, beyond these generalities there is nothing much that is concrete. Significantly, there is no mention of the issue of unions of gig workers being recognised by the platforms. There is also no mention of what will be done in terms of data security and privacy for the data that is collected for all transactions that take place on platforms.

The Tamil Nadu government is contemplating creating a similar law, while the Karnataka government has made a budgetary provision for paying the premiums of life insurance policies taken out for gig workers.

The formation of unions for platform workers in recent years is cause for cheer. The global fight has been led by Amazon warehouse workers, who voted to start a union in Staten Island. Their efforts were recognised by the National Labor Relations Board, but Amazon has been fighting back. Starbucks’ workers staged walkouts in Seattle in March 2023. Last year also saw a battle between Hollywood script writers, represented by the Writers Guild of America, and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (representing old Hollywood studios and streaming companies) over AI replacing human writers. The Guild seems to have a victory of sorts, in that it negotiated for the studios to agree to sharing the profits from using AI with the script writers. Protests and strikes are rising, so there is some hope in the resistance.

In India too there are now unions specifically for gig workers. The largest organization is the All India Gig Workers Union, founded in 2020, representing mostly food delivery workers, and iaffiliated to the Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU). There is also the Indian Federation of App-based Transport Workers, founded in 2019 in Mumbai. Gig worker strikes have become more frequent now in India. Blinkit – a delivery platform – had its workers protest a reduction in commissions in April 2023. July 2023 witnessed the protest of workers, mostly women, from Urban Company, against arbitrary blocking.

Futures and resistance

Many current economic analyses state that growth has become more jobless in the neoliberal era, starting from the 1980s, and this trend has intensified with digital technologies becoming mainstream around the late 1990s. The total number of jobs is falling in absolute terms, and the new jobs are far fewer than the jobs lost. Consider the impact of Generative AI. The new jobs that are being created are minuscule in number and require new skills (think AI developers, and ‘prompt engineers’ who write cues to ‘prompt’ AI tools to deliver appropriate responses); many conventional jobs will be reduced drastically, such as coders, data entry operators, customer service personnel, analysts of various types. These will be pushed into the ‘new informal’ (gig) economy. We can also immediately see the ‘creation’ of inequality where a small number of people will get high wages, but many more will be forced towards precarity.

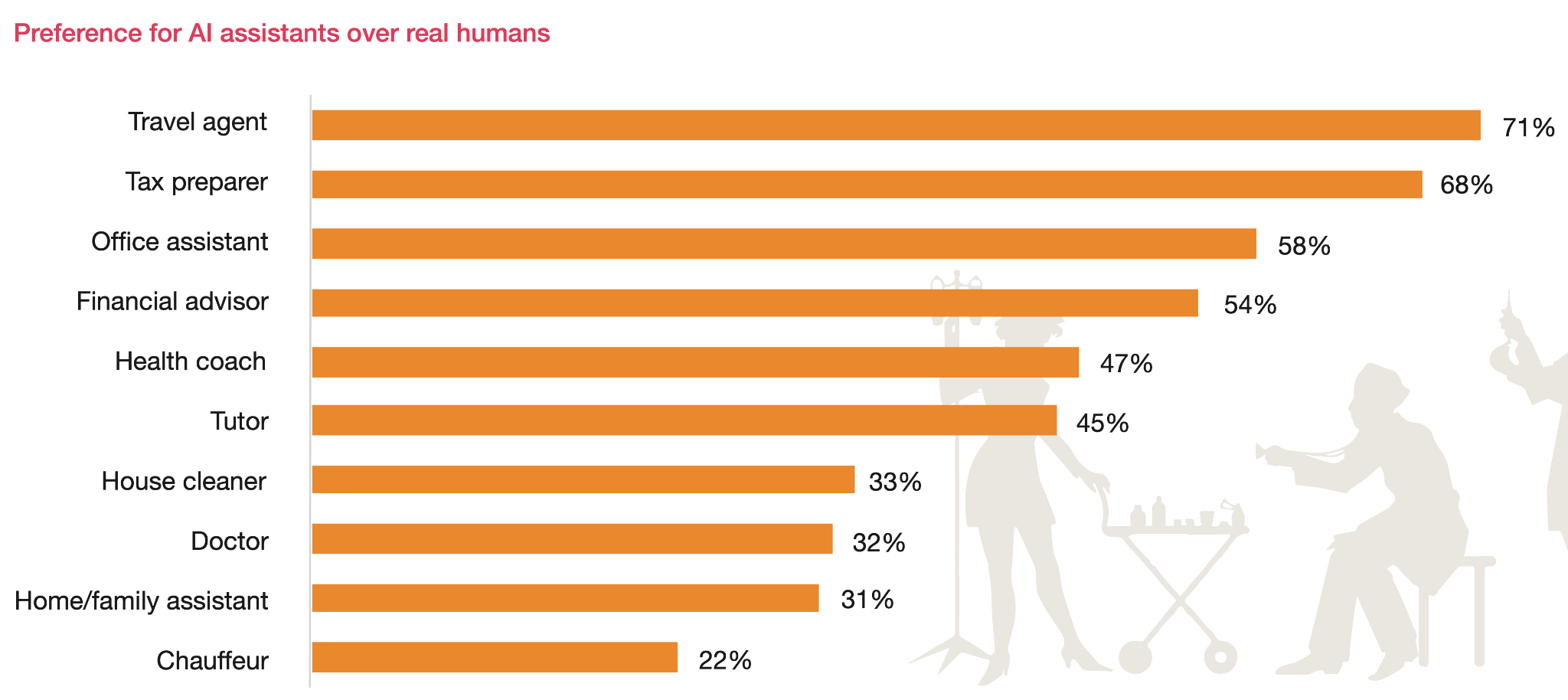

AI will come for more and more jobs – and this time white collar jobs are under attack. A PwC survey of corporate sector professionals has some India-specific insights as to what kind of job profiles are likely to be replaced. The chart below shows the percentages of surveyed persons who preferred AI assistants over humans for various types of work.

In general, jobs that require collating material (report writing, tax preparers), standard document creation (e.g. legal briefs) or any work that is administrative and repetitive are under threat. A more recent survey reveals similar tendencies. More notably, a lot of creative professionals will also be affected: artists, musicians, scriptwriters, coders, and strategists, as generative AI penetrates these activities. We can expect inequality to rise even further consequent upon losses due to un- or under-employment and the replacement of human-made products by AI-generated ones.

The talk of Universal Basic Income (UBI) – an amount that will be available to everyone – has seen much greater traction over the last decade or so. India will likely see a new twist to this issue. UBI, in India, is also looked upon as a potential cash-transfer candidate to “fight” poverty, but now a new twist to this is likely in view of the exacerbation of job losses due to AI. An insightful commentary in The Guardian says, “While it is still considered by many to be a radical concept, proponents of a universal basic income (UBI) no longer see it only as a solution to poverty but as the answer to some of the biggest threats faced by modern workers: wage inequality, job insecurity – and the looming possibility of AI-induced job losses.”

Everyday life and exclusions

New digital technologies directly exclude those who cannot afford them and thus have no or limited access.

The CoWIN app that was used to schedule Covid-19 vaccine appointments is a good example of such exclusion. The Government, at that time, was more interested in showing off its ‘technical prowess’ – which then becomes evidence of us being ‘VishwaGuru’ – in ‘managing’ vaccine delivery rather than ensuring equitable access to the vaccines. Perhaps it also showed that the Government cares more for the affluent who use the internet and its apps easily, rather than the lower socio-economic classes who can barely touch the fruits of modern technology. The other benefit to the State of adopting such a technological pathway was that lots of user data could be collected and harvested.

At that time I wrote about this, “This cheerleading masks the basic truth about the stupendous extent to which the CoWIN platform actually ensures that millions of Indians will not have access to vaccine appointments. Around 33% to 45% people in the 18-44 age group – approximately 200 million to 280 million people – have no or poor access to the internet or any online platforms. There are other barriers too. Though the CoWIN app is multilingual, many Indian languages are missing from it. Besides, the portal is only in English. Further exclusion may arise from factors such as location ( from areas with poor connectivity), gender (internet usage is skewed in favor of males), and education levels.”

CoWIN was the only pathway to scheduling appointments, and the Government’s solution to the problem of lack of digital access and literacy was that such disadvantaged people should approach Common Service Centres for assistance. It was oblivious to the fact that many of these centres were barely functional because of Covid-19 restrictions!

Another notable example of the consequences of the digital divide is education. Anything that requires the use of the internet or a laptop puts those who have poor access at a disadvantage. This was most evident during the Covid-19 pandemic when all teaching moved online. At the very least every student needed a mobile phone with a data connection to attend classes. For many students these were hard to get and they suffered. The worst affected were Government schools, which are also typically underfunded. In addition to the lack of devices and expensive data plans, the poor quality of Internet access and unreliable data networks in many places added to the problem.

The continuing emphasis on the use of online technologies even in the post-Covid era has made this issue persistent.

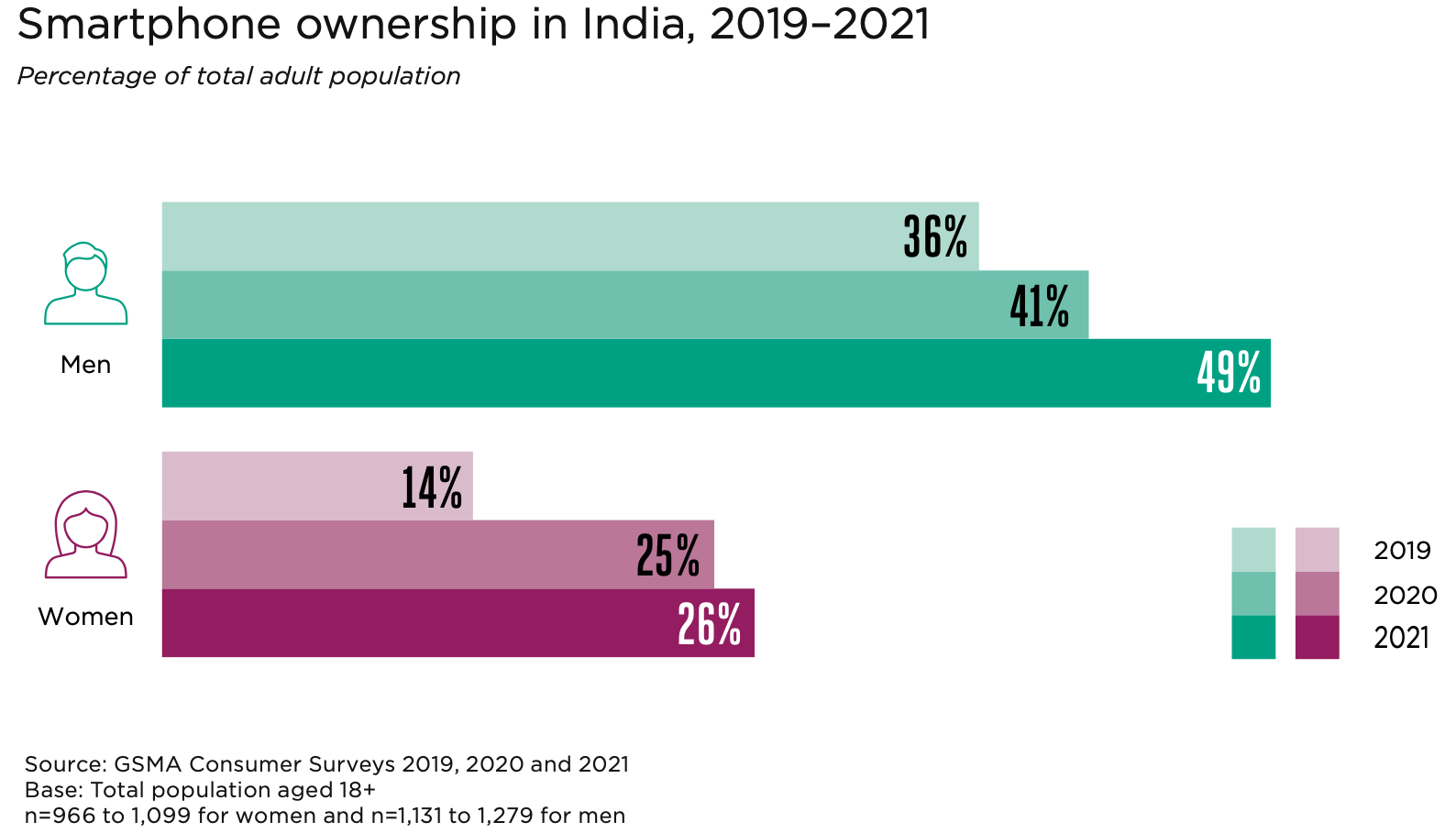

The digital divide also persists over gender. Over the years smartphone usage has increased for everyone, but it is more for men than women, as also the use of the internet. This has much broader consequences in terms of the scope and scale of the kind of activities that a person is able to do when accessing the web or apps, such as finding a job or a gig, social and professional networking including the use of social media platforms. The data from the Mobile-Gender Gap Report 2022 illustrates this vividly.

The just published ASER report indicates that in rural India, more boys owned smartphones than girls and that boys knew how to use them more effectively as well.

Above Graphics Taken from Mobile-Gender Gap Report 2022

Finally, nothing illustrates the nature of digital exclusion better than the ‘Aadhaar card’. The Aadhaar project was launched in 2009, with its stated limited objective being to associate a unique identity number with every beneficiary of public welfare schemes. This was to better target and monitor the benefits associated with these schemes. After a rough journey full of disputes over data privacy and security, legal challenges to Aadhaar-related legislations and various Supreme Court orders, this ID is now used for everything and anything. Once the State realised the ease with which any individual’s activity could be tracked through this ID, it has been made (in practice) mandatory for opening bank accounts, buying SIM cards, applying for scholarships, and filing tax returns, and now attempts are being made to link it to voter IDs.

Making Aadhaar registration mandatory for almost everything has led to a situation where all kinds of data of different kinds are now ‘linked’ via Aadhar. This in itself poses a huge risk that one’s ID can be ‘hacked’ to get access to so much private data of citizens. A variety of organisations, including private ones, now store Aadhaar numbers and associated information on poorly secured servers. But unfortunately, neither are there any legislative privacy safeguards, nor are there court orders that can stop this untrammeled accumulation and proliferation of personal data. Data breaches have been reported multiple times (1, 2, 3) but nothing has changed. A more dramatic development is the stealing of biometric data from public records such as land registries, cloning a fingerprint on silicone and then withdrawing money using the Aadhaar number and the cloned fingerprint!

Yet the biggest travesty is the manner in which Aadhaar based identity authentication leads to multiple types of exclusions. Examples abound.

A sample survey by the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) found that 88 per cent of ration cards (which are used by the most vulnerable sections of society to access subsidised food grains) canceled by the Jharkhand government because of ‘failures’’ in linking these cards to Aadhaar belonged to genuine households. The J-PAL investigators said that while there was some weeding out of ‘ghost’ beneficiaries, there were huge exclusion errors. The Government has been at pains to claim that they have saved huge amounts of public money by this weeding out process. Jean Drèze, an economist from Ranchi University, commented, “To claim that it was successful in reducing corruption is like shooting at the tyres of a car and counting the reduced traffic as a bonus.”

In Madhya Pradesh, the VanMitra Portal was launched to ease the process of registration of land titles for tribals under the Forest Rights Act. Almost everyone who filed claims could do so only with some assistance, due to lack of ‘technical knowledge’. The rate of rejection of filed claims, after review through VanMitra, ranged from 70.3 per cent to 98.86 per cent in 30 districts. People are on tenterhooks, and in some cases they have been harassed by forest officials for cultivating their land; in some cases they have also been evicted.

In April 2022, the Odisha government moved from paying pensions in cash to doing so by bank transfer. It had previously decided to link pension accounts with the Aadhaar ID. In June 2022 the state government reverted to cash payments because many ‘unlettered’ pensioners could not handle bank payments, due to lack of infrastructure, lack of access to a bank branch, biometric failure, poor internet connectivity and digital illiteracy. Central government pensioners still receive money in their banks, with all the attendant difficulties.

The Union government has made it mandatory to make wage payments for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) scheme through the Aadhaar-based payment system (ABPS). This requires that job cards of workers be linked to the system. A significant number of workers have not been able to link their job cards which has resulted in their jobs cards being deleted. A report in The Hindu states that, “According to LibTech India, a consortium of academics and activists, 7.6 crore workers have been deleted from the system over the last 21 months.” This issue continues to fester.

In an article in Scroll, Jean Drèze and Reetika Khera have summarised all that is wrong with this grand digital scheme – Aadhaar,

Excluded citizens, now ‘labharthis’

The social classes that face technological exclusions today are the products of a system where the Government and its institutions have failed to provide economic and educational benefits rightfully due to them. Technologically-driven unemployment and precarity are adding more people to this pool everyday.

There seems to be an acceptance of this idea by policy makers that this situation is ‘permanent’ and is ‘too difficult’ to remedy, and therefore welfarism is the only balm that can be applied. It is here that we notice a remarkable confluence: digital technologies, enmeshed within capitalist structures which are partly responsible for producing precarity, are also the ones that facilitate the ‘New Welfarism’ of direct transfers, Aadhaar and health IDs, biometric and GPS tracking, ubiquitous data dashboards, and so on. This digital infrastructure is also the kingpin of new India’s ‘technological might’. It also comes with added benefits of ‘efficiency’, ‘savings’, a narrative that obscures the reality of so much exclusion.

Those who are left out of vikaas (development) are no longer citizens with entitlements and rights but mere labharthis waiting for doles to be handed out to them at the whims of the political class. Thus, direct bank transfers via ‘leading technologies’ like Aadhaar are delivered by a caring Government and its great leaders. Public goods like healthcare (insurance policies) and education (scholarships, laptops and even books) and private ones (cooking gas, toilets) are now being delivered in this mode. These are now substitutes for what a citizen should have accessed as a matter of right if s/he had been a part of vikaas.

Epilogue

We are now in the midst of a techno-capitalism that is creating jobless worlds, tiny super-rich elites, and obnoxious inequality besieged by an aspirational, thoughtless consumerism.

Ontologically, the idea of technological solutionism – whereby ‘everything’, including political and social issues, has a technical solution – is now rampant, driven largely by digital BigTech corporations. It facilitates the replacement of the notion of political conflict by an apparently apolitical, techno-managerial framework. It also spawns fantastical narratives of techno utopias without addressing any real issues. It remains to be seen what deeper crises unfold now and what kind of social resistance arises to confront this onslaught.

- ‘Cloud’ refers to storage and services provided by remote computers accessible via the internet. ↩︎

- Subramanian, Sreenivasan (2019) “What is happening to rural welfare, poverty, and inequality in India?”, The India Forum. https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/what-happened-rural-welfare-poverty-and-inequality-india-between-2011-12-and-2017-18.

Subramanian, Sreenivasan (2021) “Pandemic-induced Poverty in India after the First Wave of COVID-19: An Elaboration of Two Earlier Estimates”, The Hindu Centre for Politics & Public Policy. ↩︎ - There is DigiYatra – based on facial recognition – for seamless passenger movement through airports; reportedly, passengers are being ambushed into being “photographed. And then there is ASTRA – another facial recognition software for issuing SIM cards. ↩︎

- There is debate whether the ‘precariat’ is a class by itself. Indeed, it is not – we merely use this as category to denote individuals who share certain social characteristics. See https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii84/articles/jan-breman-a-bogus-concept. ↩︎