According to India’s rulers, India is not only a global power, but a Vishwaguru – a Global Teacher. This claim may not be borne out by the level of Indians’ per capita income, productive employment, farm output per hectare, manufacturing strength, technological base, educational status, nutrition, or health. Nor do the distorted structure of India’s employment, the abysmal economic status of its women, or the overall lack of political and social freedoms support the claims to Global Teacher status.

In one sphere, however, India’s achievement has won global recognition: that is, in its high-speed drive for digitalisation. In the view of the American billionaire Bill Gates, “No country has built a more comprehensive [digital] platform than India.”1 The Indian billionaire Nandan Nilekani, the most prominent evangelist for digitalisation in India, claims that “India is upgrading – from an offline, cash, informal, low productivity economy to an online, cashless, formal, high productivity economy.”2

These claims are bolstered by international financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). According to the World Bank’s World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends,

Technology can be transformational. A digital identification system such as India’s Aadhaar, by overcoming complex information problems, helps willing governments to promote the inclusion of disadvantaged groups…. a digital ID, by giving millions of poor people an official identity, increases their access to a host of public and private services.3

A widely-cited IMF study of March 2023, Stacking up the Benefits: Lessons from India’s Digital Journey,4 treats India as a development model: “India has developed a world-class digital public infrastructure (DPI) to support its sustainable development goals…. India’s journey highlights lessons for other countries embarking on their own digital transformation.” Although the IMF study is short on actual evidence about the benefits of India’s digitalisation, it is useful as a summary statement of the claims themselves.

According to the IMF study, India’s ‘digital public infrastructure’ – comprising digital identity (principally Aadhaar); digital payments systems (principally Unified Payments Interface [UPI]); and data exchange (such as DigiLocker) – has had a range of positive effects. These include:

— increasing the efficiency of Government transfers to the poor;

— lowering the costs of public programmes;

— increasing Government revenues;

— reducing corruption and errors of inclusion and exclusion in Government programmes;

— accelerating the formalisation of the economy;

— improving the transparency and accountability of Government;

— improving ‘financial inclusion’ and the penetration of financial services;

— improving the selection of borrowers/insured persons;

— enabling new digital businesses;

— making public and private services in health and education more convenient, speedy and efficient;

— enabling more convenient payments systems that benefit both consumers and firms, including micro, small and medium enterprises (especially smaller merchants); and so on. The study projects that “Further progress in digitalization could improve India’s productivity in the medium and long term, lifting potential growth above pre-pandemic levels….”

In the present collection of articles, we look at the impact of digitalisation on the economy as a whole, as well as on specific sectors. We place this digitalisation in the specific context of India’s economy and society, and we argue that the manner in which it is being carried out serves a specific class agenda.

Digitisation vs digitalisation

The terms ‘digitisation’ and ‘digitalisation’ are used interchangeably by many people; others draw distinctions between the two, some adding a third term, ‘digital transformation’; but there does not appear to be a standard usage. We adopt the following usage:

‘Digitisation’ refers to “the process of converting information into a digital (i.e. computer-readable) format.”5 For example, scanning a set of family photos converts them into digital format (encoding them using the digits 0 and 1.)

‘Digitalisation’ refers to the use made of digitised data and digital technologies for various social and economic processes. In the case of a business enterprise, examples of ‘digitalisation’ may include digital marketing; receiving payments through digital channels; analysing data generated throughout the business organisation, and on this basis reorganising the business process; changing the business model itself to provide services from the ‘cloud’; and so on. In the case of the State, it may include creating digital records and identities; providing information to the public through the internet, and channels for the public to interact with the State machinery; providing services such as education and healthcare through digital channels; using digital technology to improve the efficiency and monitoring of various services; shifting the filing of returns and administration of taxes to the digital mode; making digital payments of wages and welfare transfers; providing private firms access to databases containing citizens’ data; and so on.

Thus, an individual may digitise his/her own photograph, iris scan, fingerprints, address, date of birth, and parent’s name; however, when, say, the State does these actions, and on that basis creates a digital identity (such as Aadhaar), that is an act of digitalisation. Once created, this digital identity may acquire extraordinary significance, even overpowering the person it claims to identify; thus the failure of a person’s fingers to match the Aadhaar fingerprints routinely leads to the denial of rations, wages, welfare payments, and so on. The Aadhaar is real, the person in question may be treated as fake.

Rapid advance of digitalisation

Undoubtedly, digitalisation has advanced in India at a rapid pace in the last 10 years, which we will refer to as the period of ‘peak digitalisation’. This can be seen in the growth of digital payments, the emergence of new firms based on digitalisation, and the shifting of transactions between the Government and citizens to the digital mode. To take a few examples:

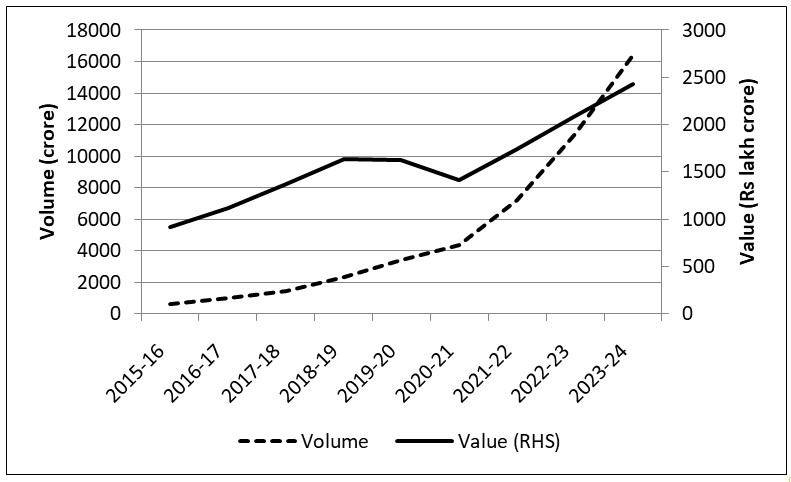

— Digital retail payments have grown between 2016-17 and 2022-23 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 51 per cent in volume and 27 per cent in value terms.6 India’s digital consumer base is said to be the second largest in the world, and growing at the third fastest rate amongst major economies.7 In the period since the Covid-19 pandemic, credit and debit cards in circulation crossed the 1 billion mark. Transactions using the Government’s RuPay card grew at a CAGR of approximately 40 per cent between 2016-17 to 2021-22.8 As can be seen from Chart 1, in the last five years the volume of transactions has been growing faster than the value, indicating that digital modes are being increasingly used for small payments.

Chart 1: Volume and Value of All Digital Payments, India

— The ‘FinTech’ industry has captured a sizeable share of the market of non-banking financial corporations (NBFCs), Of the 14,000 newly founded start-ups between 2016 and 2021, close to half belonged to the FinTech industry. An RBI report claims that FinTech lending is poised to exceed traditional bank lending by 2030.9

— The Government has shifted the transfers it makes to Indian citizens to the ‘Direct Benefit Transfers’ (DBT) mode. In 2023-24, the Government claimed to have carried out 7.2 billion DBT transactions to transfer Rs 5.9 lakh crore (Rs 5.9 trillion) to various individuals under 314 schemes; of this, Rs 2.6 lakh crore was in cash, and Rs 3.3 lakh crore in kind (principally rations, fertiliser, and cooking gas).10

Chart 2: Direct Benefit Transfers, in Cash & Kind

— In turn, citizens engage with, or are compelled to engage with, the Government through digital channels. As of July 31, 2023, nearly 1.37 billion Aadhaar numbers had been generated, and Aadhaar had been used for almost 103 billion authentications.11 The Goods and Services Tax Network (GSTN), launched in 2017, records invoice level data from every GST-registered business in the country, on the basis of which input tax credits are calculated. Between GSTN’s start in July 2017 and end-March 2022, newly registered GST taxpayers (i.e., apart from those already registered under the earlier indirect tax regime) rose to 8.8 million.12

Digital infrastructure

The Government of India’s creation and ownership of the ‘India Stack’ serves as digital infrastructure for this digitalisation drive. The India Stack consists of three layers: establishing identity (Aadhaar), payments systems (Unified Payments Interface, Aadhaar Payments Bridge, Aadhaar Enabled Payment Service), and data exchange (DigiLocker and Account Aggregator). This infrastructure required large State investments (the costs of the Aadhaar programme alone have been estimated at $10-12 billion13), but steeply lowered the costs for digitalised businesses to authenticate and acquire customers and receive payments. The use of Aadhaar, according to Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, has brought down the cost of customer acquisition for a firm from Rs 500-700 ($6-9) per person to Rs 3 (0.4 cents).14

Several steps taken by the Indian government in recent years were key to this process. In January 2009, the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government set up the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), appointing Nandan Nilekani as the chairman. The UIDAI began collecting the biometrics and demographic data of residents of India and allotting each such person a 12-digit unique identity number, the Aadhaar, and the UPA government began using it for verification purposes of banks, telecom companies and government departments; in 2012 it launched a Direct Benefits Transfer scheme. “We felt speed was strategic. Doing and scaling things quickly was critical. If you move very quickly it doesn’t give opposition the time to consolidate,” said Nilekani.15 As yet the entire Aadhaar project had no legislative backing. In 2013 the Supreme Court ruled that the scheme was voluntary, and the Government could not deny a service to anyone who did not possess an Aadhaar.16

Although the BJP campaigned against the Aadhaar before it came to power, the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance government quickly embraced the project. Following a July1, 2014 meeting between Nilekani, the Prime Minister and the Finance Minister, the new government re-launched the Aadhaar drive with redoubled energy, providing it legislative backing. Moreover, in August 2014, the Prime Minister launched the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana, under which more than 520 million no-frills, low-cost bank accounts have been opened to date,17 almost exclusively by public sector banks.

These two measures, combined with the spread of mobile telephony, enabled what the Economic Survey 2014-15 called the “JAM Number Trinity” – Jan Dhan Yojana, Aadhaar and Mobile numbers, a coinage of the then Chief Economic Advisor (CEA), Arvind Subramanian. The Survey claimed that subsidies were not a good way to fight poverty. Among other things, it argued that subsidies distort prices, resulting in an inefficient allocation of resources in the economy.18 It proposed eliminating or phasing down subsidies on food, energy, fertiliser, rail travel, and other goods/services, and replacing them with targeted transfers to a narrowly defined category of the ‘poor’:

If the JAM Number Trinity can be seamlessly linked, and all subsidies rolled into one or a few monthly transfers, real progress in terms of direct income support to the poor may finally be possible. The heady prospect for the Indian economy is that, with strong investments in state capacity, that Nirvana today seems within reach. It will be a Nirvana for two reasons: the poor will be protected and provided for; and many prices in India will be liberated to perform their role of efficiently allocating resources in the economy and boosting long run growth.19

Indeed, the celebration of the magical powers of digitalisation is closely linked to neoliberal economic theory.

Digitalisation and neoliberal economic theory

Keynesian economic theory, dominant in western capitalist countries from the end of World War II to the 1970s, held that the level of economic activity is basically determined by the level of aggregate demand. Unlike Marxists, Keynesians did not view the periodic crises of capitalism as manifestations of an irreconcilable social contradiction. But they also did not believe the ‘free market’ would spontaneously and continuously ensure full employment. They acknowledged that capitalist economies tended to suffer periodic slumps in demand, during which private capitalists failed to invest, workers lost their jobs, and demand consequently spiralled downward. In such circumstances, they argued, the State should intervene in order to stimulate demand through Government spending and reduced interest rates, till private investment kicked in and revived employment.

By contrast, neoliberal economic theory, dominant since the 1980s, worships ‘the Market’. It considers that, as long as the State, trade unions and the like do not interfere with ‘free’ markets, full employment will automatically materialise. In the world of neoliberal theory, each atomised individual enters into exchange with a universe of other atomised individuals, in a freely competitive process. (For example, each worker individually contracts with the capitalist to sell his/her labour for a wage, and neither party can set the terms.) This theory argues that, in a truly free market, prices automatically adjust in order to ensure full employment of all factors of production (for example, in a free market, wages fall to the point at which capitalists find it profitable to hire workers once more). At times of crisis and collapse of demand, what is needed are ‘structural reforms’ to allow markets to clear – for example, changing labour laws to allow wages to fall, winding up public procurement to force farmers’ sale prices to fall, changing land/environmental laws to bring more land on the market, and so on. All prices are simultaneously determined (by demand and supply), and all markets clear completely, ensuring full use of resources. In the view of neoliberals, this guarantees an optimal outcome in all situations.

Neoliberal theory, taken at face value (i.e., without examining the class interests behind its promotion) is thus a type of magical thinking or religious belief in the free market. For capitalists, it has the attractive feature that, since all outcomes of the market are the best possible in the circumstances, they are all justified.20

When agencies such as the IMF, the Indian authorities and pundits like Nilekani promote the notion of a digitally empowered utopia, they are merely embellishing existing neoliberal theory with magical notions regarding technology. One of the weaknesses of neoliberal theory is that it assumes that all participants in the market are equally and perfectly informed; with the revolution in information technology, neoliberal theorists believe that this Nirvana is within reach.

For example, the IMF paper cited earlier says that “DPIs [digital public infrastructures] act as digital building blocks to drive innovation, inclusion, and competition at population scale.” (emphasis added) According to the paper, digitalisation drives the formalisation and transformation of the economy, penetration of financial services, extension of credit to underserved sectors such as micro, small and medium enterprises, more efficient health and education services, and so on.21 All of these goals were earlier the job of the State, requiring specific measures and budgetary allocations.

After many struggles by India’s peasantry to obtain decent prices for their crops, the Indian government instituted in the 1960s a system of public procurement of foodgrains at minimum support prices. There still is a widespread demand among the peasantry for this system to be extended to other crops as well, and an intransigent refusal by the Indian State to do so. Neoliberals, by contrast, believe that prices should be “liberated to perform their role of efficiently allocating resources in the economy”. All that is needed is to link all agricultural markets to a national digital platform and thereby provide a “transparent price discovery system”. Moreover, in place of the Government directing a specific percentage of bank credit to agriculture, ‘fintech’ firms can assess the ‘creditworthiness’ of agricultural borrowers, even the smallest ones, through analysis of transactions data and other data. To minimise any pains of the transition, some minimum income can be provided as handouts to peasants through Direct Benefit Transfer.

In earlier times, the Indian working class had fought long struggles to compel the colonial and later the post-colonial Indian State to enact labour laws regulating relations between the capitalist and workers. Although these were enforced for only a minority of workers, they became immediate struggle-demands for other workers as well. However, digital firms such as Uber and Zomato pose as mere platforms through which individual customers and suppliers of services can meet and strike deals, without any labour law or social protection: the epitome of the neoliberal vision of the market.

In brief, the magic of digitalisation is meant to substitute Government intervention with respect to boosting aggregate demand, addressing the basic needs of the people (healthcare, education, credit) as well as the special needs of specific sections, setting up the physical infrastructure and institutions needed for these purposes, sustaining peasant agriculture, and regulating capitalist-worker relations.

Trauma, coercion, and digitalisation

Given this ideology, the digitalisers present digitalisation as a spontaneous, voluntary, ‘people-driven’ process. A typical article on the subject is replete with clichés such as the following:

India is a very large country of very young people…. India’s population isn’t just young, it is connected…. These young Indians are aspirational and motivated to use every opportunity to better their lives…. It’s about finding innovative solutions to address pressing problems in health care, education, agriculture, and sustainability…. The Aadhaar is a 12-digit unique identity number with an option for users to authenticate themselves digitally—that is, to prove they are who they claim to be…. the data remain under the citizens’ control, further encouraging public trust and utilization.22

The fact is, the use of digital payments in India has been pushed by three great traumas to the people: demonetisation, the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax, and the Covid-19 lockdown.

1. The November 8, 2016 decision of the Modi government to invalidate large denomination currency notes (which accounted for 86 per cent of the cash in circulation) dealt the Indian economy, particularly its vast informal sector, a terrible blow. Nilekani saw it as an opportunity: “Demonetisation will help digitisation of the economy and the roll out of digital financial services. What could have taken about six years can now be done in six months.”23 The IMF paper remarks: “While it was disruptive, demonetization led to greater use of other forms of payment, including the UPI.”24

Indeed, less than two months later, the Prime Minister presented demonetisation as a step taken consciously to promote digitalisation: as a result of demonetisation, he declared, cashless transactions had increased by 200-300 per cent.25

2. The imposition of GST had an even more severe impact on the informal sector. Heavy compliance costs, the blocking of working capital (since GST payments have to be made whether or not the purchaser’s payment is received), and the loss of market for units without GST-registration wiped out units and employment. A survey-study of small firms found that more than 50 per cent experienced a fall in turnover of 10-30 per cent; another 36 per cent of firms reported a fall of over 30 per cent. More than 50 per cent of the firms retrenched workers after the imposition of GST, with average employment per unit falling 17 per cent.26

The IMF paper entirely ignores this catastrophic outcome and merely commends the increase in the number of taxpaying firms as a result of GST. The Economist rejoices in the belief that GST and digitalisation are driving the “formalisation” of the Indian economy, and looks forward to the day when the informal economy’s “sights, sounds and smells may be less pervasive in future”; “Imagine”, it says, “an India without hawkers.”27

3. The sudden nationwide lockdown imposed in anticipation of the spread of Covid-19 went even further than the earlier two steps in shutting down the informal sector for an extended period. However, in the words of the RBI think tank CAFRAL, Covid-19 was “An opportunity for FinTechs”: “Consumers and businesses were forced to move online, and digital activity increased globally…. FinTech lenders, already at the forefront of the digital lending revolution, could exploit the inherent advantages of limited manual intervention and face-to-face interactions to cater to a range of consumers.”28 India’s official investment promotion agency boasted that “Covid-19 has accelerated India’s digital re-set”: “The country was already on a digital-first trajectory with one of the highest volumes of digital transactions in the world when the pandemic struck, and further propelled the use of contactless digital technology.”29 The Chief Economic Advisor expressed satisfaction that “The pandemic played an instrumental role in accelerating the pace of digitization and that the sectors of education and healthcare are some of the key areas where digital economy will play a key role going forward.”30

The adoption of Aadhaar itself has been presented as purely voluntary, indeed, a demand of the people themselves. Bill Gates tells us that “For the last decade, Nandan Nilekani has been working to make these ‘invisible people,’ as he calls them, visible by giving them access to official identification…. there is growing awareness in the global community that with a proof of ID, the world’s poorest people have a powerful tool to be seen, heard, and improve their lives….”31 Says Nilekani, “Aadhaar e-KYC has been revolutionary in making life simpler for people”.32

Had the Aadhaar been adopted voluntarily by people, had it been ‘people-driven’, the Government would not have needed to make it compulsory, in practice, in order to obtain a SIM card, a birth certificate, a death certificate, a bank account, a school midday meal, benefits under any Government scheme, school admission, and so on. As Jean Drèze remarks, “saying that Aadhaar is voluntary is like saying breathing or eating is voluntary.”33

About the articles in this joint issue:

The collection begins by looking at digitalisation and India’s economy as a whole, and the role of Government policy.

Arun Kumar discusses the ‘unorganised’ or informal sector, which accounts for the bulk of employment in India. It also accounts for a sizeable share of non-agricultural production. He points out that Government policy measures such as demonetisation, the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and the Covid lockdown, which have accelerated digitalisation, have also dealt heavy blows to the unorganised sector. Nevertheless, the extent of damage may not get reflected in official GDP data, because the methodology used to calculate GDP is faulty. Since the unorganised sector output is directly surveyed only at long intervals, in the periods between surveys its output is estimated using data for the growth of the organised sector. This methodology fails to take account of the shocks administered to the unorganised sector, and thereby invisiblises the damage done to it. He further warns that, since digitalisation gives the organised sector an advantage over the unorganised, and the organised sector is dominated by large corporations, many of them multinational corporations (MNCs) or with substantial investment by the MNCs and foreign portfolio investors (FPI), digitalisation is increasing international finance capital’s hold over the Indian economy.

Anurag Mehra describes various ways in which inequality and precarity in India are being accentuated by the process of digitalisation. New technology is destroying jobs, beginning with the robotisation of factory jobs. Using digital platforms, more and more categories of work are being converted into ‘gig’ employment. This turns the worker into a supposed ‘independent contractor’, in fact a worker without job security or employee benefits. The gaps in access to, and familiarity with, digital technology widen the existing divide among different social sections. And the digitalisation of welfare rights leads to large exclusions. The combined effect of all these processes is to push vast numbers of workers into a state of ‘precarity’. “It remains to be seen”, he says, “what deeper crises unfold now and what kind of social resistance arises to confront this onslaught.”

Since the IMF and the Indian government have made extravagant claims about the beneficial impact of digitalisation on India’s economy, the Research Unit for Political Economy (RUPE) looks at India’s overall economic performance during the period of what it calls ‘peak digitalisation’, 2014-24. This decade has witnessed lower growth than the previous decade, even if one excludes the Covid-19 years. Consumption has remained depressed, and investment has collapsed. Crucially, rather than the workforce shifting to formal, high-productivity sectors, a growing share of the workforce has been pushed into low-productivity, low-income sectors, indicating growing desperation. Wage and income levels have declined in the last decade. While these developments may not be caused by digitalisation as such, they hardly offer evidence of the beneficial macroeconomic impact of digitalisation. The data indicate that the digital sector is not getting further integrated with the rest of the economy. Rather, it is developing as an enclave, disarticulated from the rest of the economy. The gap between the growth of the digital sector and the non-digital sector is widening (with the non-digital sector growing at only one-third the pace of the digital sector); and the digital industry is increasingly tied to the international economy, not the domestic economy.

The IMF study claims that digitalisation has increased the efficiency of Indian government transfers to the poor. How is this increase in efficiency measured? If we take ‘efficiency’ to mean maximising the output for a given level of inputs, we would need to measure both the amounts transferred and the amounts received by the intended recipients, assigning weights to any errors in this process. As Rajendran Narayanan points out, inclusion errors (i.e., giving money to ‘undeserving’ persons) may have fiscal costs for the Government, but exclusion errors (i.e., denying money to ‘deserving’ persons) may cost the life of a person; yet governments focus on preventing the first type of error, disregarding the second. With the advent of digitalisation, exclusion errors not only persist, but are getting automated, and placed beyond the reach of mass protest and agitation. He provides detailed evidence of how this is so in the case of NREGA payments, for which Aadhaar has been made the central technology. The yawning gap between the digital world and the real world is brought out in what are called ‘last mile challenges’. This innocuous-sounding phrase refers to the heavy costs, in time and money, incurred by rural workers in actually obtaining their own hard-earned earnings, which in the digital books of the Government is already considered to have been ‘transferred’. Finally, Narayanan calls for replacing the ‘Know Your Customer (KYC)’ framework with a ‘Know Your Rights’ framework (in the context of Government payments to citizens); for workers and ration card holders are not ‘customers’ or ‘beneficiaries’, but citizens with rights.

RUPE finds that, despite the vast exercise of imposing GST on the economy, and despite the much-advertised use of ‘big data analytics’ by the Income Tax Department to sniff out tax evaders, the tax/GDP ratio has stubbornly refused to rise for the last 15 years. The share of direct taxes has fallen by almost 5 percentage points since 2009-10, i.e. taxation has become more regressive. A number of studies and articles by various authors have taken apart the claims by the IMF and the Government that digitalisation has brought about large fiscal savings. What has taken place instead is widespread violation of rights, such as the denial of rights to rations, with grave implications.

Next we turn to the digitalisation of specific sectors: health, education, urban planning, retail credit, and agriculture.

Indira Chakravarthi shows how international agencies such as the Gates Foundation, the World Bank and the World Health Organisation (WHO) helped set the agenda of the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY), pushing the financialisation and digitalisation of healthcare. Whereas the historical experience of countries which improved their public health and universalised healthcare shows that India should not make technological ‘innovation’ in health its priority. Instead, India should strengthen its chronically under-funded and under-staffed public health infrastructure, particularly in rural/peripheral areas, and address the social determinants of health (income and social protection, education, employment, working conditions, food security and quality of nutrition, housing, environment, social inclusion, etc). Ignoring this basic truth, the Government is now focussed on centralising personal health data in a digital form and making it accessible to the corporate sector, as Chakravarthi shows through her analysis of the National Digital Health Mission (NDHM). The present digitalisation drive has little to do with public health, but much to do with enabling the corporate sector, including global tech giants, the use of India’s healthcare data in the pursuit of private profit.

Rahul Varman and Manali Chakrabarti lay out the context in which education in India is being digitalised. The children of any society are its future workers and citizens. How productive and democratic the country will be in future depends to a significant extent on the nature of their education. However, with the help of World Bank guidance over the decades, India’s rulers have made a shambles of the public schooling system. The educational outcomes are dismal. Even poor parents are shifting their children to private schools, incurring heavy costs in the process. The Government’s policy body, the Niti Aayog, has taken this process to its logical conclusion by calling for public schools to be handed over to be run by private firms. For all these ills, the Government’s solution is digital education. As part of this, the Government has encouraged the frenetic growth of fly-by-night ‘edtech’ corporates like Byju’s, invasive interventions by private philanthro-capitalists such as the Gates and the Nilekanis, and the activities of various corporate-funded non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

In an earlier piece, written during the Covid lockdown of 2020, Rahul Varman explored in detail how the shift to ‘online’ treats education as a commodity, one which can be delivered by private capital to customers in sachet sizes, like shampoo. The organic interaction between the teacher and the student, and among the community of students, is discarded, and replaced with the supply of ‘content’ – standardised, made engaging for the ‘consumer’ (the student), and delivered in short videos, of, say, 10 minutes apiece. As big business takes over education, it is assumed that all subjects can be taught online, all teachers can teach online, and all students can learn online. This ignores various social aspects of physical educational institutions and the communities that form within them, which are critical to learning and thinking. Indeed, as Varman brings out, the actual record of online teaching is miserable, even in terms of actually engaging the students and imparting knowledge, let alone developing their full human potential.

While the edtech bubble of 2020 has clearly burst, with a collapse in funding for edtech start-ups, the thrust of official policy (including the National Education Policy of 2020) remains towards ‘tech-enhanced’ teaching and public-private partnerships.34 Thus the threat of the digitalisation of education remains very much alive.

As the abysmal state of public healthcare and public schooling are to be overcome through digitalisation, so too the woeful inadequacy of basic urban infrastructure and services is to be overcome through the Smart City Mission (SCM). ‘Smartness’ here is defined as the use of information and communication technology and the Internet to address urban problems. Hussain Indorewala points out that the methods to address the major urban questions have long existed, and have not required high technology; the failure to adopt them is a political choice made by the dominant class interests. The actual practice of the SCM, which was meant to cover 100 cities across India, is revealing: Just one-fifth of the funds are for basic services, while four-fifths are for the development of elite enclaves, benefiting just 5 per cent of the area of the selected cities, and an even smaller share of the population. Under the banner of introducing ‘smartness’, international consulting firms are given control of policy formulation, public assets are appropriated, public services are privatised, and exclusive networks and enclaves are created. Thus “the promotion of digital technology as an apolitical solution for urban problems is a class politics – of interests that drive global consultant firms, technology providers, big bureaucracy, and vendor networks – that seeks to simultaneously obscure the nature of urban problems as well as the social-class dimension of ‘smart’ urbanism.”

‘Fintech’ lenders are touted as the new means for ‘financial inclusion’, which in turn is treated as the panacea for economic deprivation. RUPE looks at the actual financial state of the Indian people: their high reliance on informal debt, the high interest rates they pay on such debt, their vulnerability to financial stress at times of medical emergencies or even for routine expenditures. In these conditions most Indians engage with the world of finance only when compelled to do so, in situations of distress, and on adverse terms. Most are ill-equipped to deal with finance, and hence the ‘consent’ they give to fintech lenders may not be informed or truly voluntary. The near-absence of regulation of fintech lenders has allowed widespread abuses. This ‘Wild West’ phase may be succeeded by one in which a few giant tech firms dominate the field, but regulating such firms will be a challenge. The authorities are projecting the notion that fintech and AI have near-magical properties to enable ‘financial inclusion’. The RBI projects that fintech lending will exceed traditional bank lending by 2030. In fact, the developmental agenda, whereby finance was to be subordinated to developmental objectives, is abandoned. Credit allocation in this underdeveloped economy, which is marked by steep inequality and retrogressive social institutions, is left to ‘market forces’, and the invocation of ‘AI’ is used to mystify actual class choices.

The Government has launched a drive for the digitalisation of agriculture, India’s single largest sector of employment. We are told this will provide each farmer tailor-made technical and market-related advice, adequate and timely credit, and news about the range of prices of farm inputs and output, enabling him/her to get the best possible returns. Analysing the Government’s base paper for this drive, RUPE points out that it treats India’s vast small peasantry as profit-maximising units, along the lines of private firms; even more strangely, it treats private corporations as promoting public welfare. In fact the small peasantry are driven by the needs of subsistence, and are clinging on to their unremunerative lands for lack of employment elsewhere. On the other hand the corporate sector is driven by the profit motive, for which it will exploit any advantage digitalisation gives it over the peasant producers. Describing at length the actual condition of the peasantry, the article argues that it is operating under various compulsions, and is not in a position to take advantage of supposed market opportunities. In these conditions the State’s digitalisation drive provides the corporate sector a wealth of individualised data, and thereby further strengthens corporate power over the peasants. The major problems of India’s peasantry, and therefore of its agriculture, are rooted in social-economic relations (class relations) and State policy, and the resolution of those problems does not require digitalisation; fundamental social changes would be a prerequisite to any useful application of digitalisation in agriculture. Thus the article argues that it is necessary to reject and oppose the entire present project of digitalisation of agriculture. Finally, the article suggests that the limitations of the Indian market, as well as the likely resistance by small peasants, will put obstacles in the way of the digitalisation drive. The corporate sector may maintain a layer of intermediaries to deal with the multitude of peasants, and continue to rely on existing local power structures in the rural areas.

Finally, we place the question of digitalisation in the context of imperialism’s continuing domination over India. RUPE describes the following features of India’s digitalisation: the creation of an international division of labour in the digital economy, whereby cheap labour power in India is used to raise the rate of profit of imperialist countries’ firms; India’s continuing dependence on imports for hardware in the telecom and information technology sectors, and the large drain on this account; the domination of India’s market for digital goods and services by firms of the imperialist countries; the capture and control of data, as a raw material, by these firms; the use of foreign investment to capture economic territory in India; and the use of political influence to shut out rivals, if necessary even by war.

Recurring themes

Certain recurring themes emerge from the pieces in this collection.

1. The catchword ‘digital’ is repeatedly invoked by India’s ruling classes, the Indian authorities, and imperialist institutions such as the World Bank and IMF, to generate a certain irrational or magical thinking. They spread the notion that digital technology will somehow overcome the existing huge physical and social barriers to development, and will do this without either social change or public sector provisioning. Thus the paucity of elementary urban infrastructure and services, the inadequacy and poor state of public healthcare institutions and personnel, the poverty and maldevelopment of the ‘social determinants of health’ (i.e. the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes, such as people’s incomes, working conditions, nutrition, housing, environment, etc), the lack of investment in public schools and teachers, the limited reach of the banking network, the poor financial condition of the vast majority of people, the skeletal state of agricultural extension services, the unregulated, arbitrary and exploitative structure of the agricultural marketing system, and the impact of environmental deterioration on agriculture – all these are to be overcome by digital services provided by private capitalists in search of profit. This obviates the need for public investment in physical infrastructure and public sector employees on the ground, as also basic social change.

A corollary to this thinking is that when services are delivered by digital means, they are deemed to have been delivered, regardless of whether the ‘recipient’ actually receives any benefit of the service. A digital payment made to the bank account of a NREGA worker has been ‘delivered’, though he/she may have to incur substantial costs and miss working days to withdraw that amount. A person in financial distress who receives a fintech loan is considered ‘financially included’, despite the fact that the steep interest rates on the loan may eventually increase that distress. A student who accesses an online video has received education; a patient who accesses online consultation has received healthcare; a bus passenger who searches for the timing of the next bus on an app has received public transport; and a peasant who receives online guidance about crops has received extension services. There is little, if any, study of how far the persons who have been digitally serviced in this fashion have actually received any benefit.

2. This reflects the conception of technology in today’s dominant ideology. As one of the contributors to this collection points out, by depicting the technology itself as ‘smart’, the rulers are practising “a form of what Marx termed as fetishism: where particular social relations between people ‘assume the fantastic form of a relation between things.’” (This is similar to a religious belief which attributes supernatural powers to inanimate objects.) Technology is depicted as the outcome of an autonomous technical and economic process, obscuring the specific class interests that benefit from the development and deployment of particular kinds of technology.35

To take an example: We are told that an ‘Intelligent Transport System’ (ITS) for cities is one which combines “cutting-edge technology, data analytics, and communication systems”. To reduce traffic congestion, the system would analyse traffic patterns in order to dynamically adjust traffic signals, and deploy “smart parking solutions” to guide drivers to available parking spots.36 These technologies may have some benefits, but the proponents of ITS in India are silent about the main problem in most cities: the number of private cars. There is a ‘smart’, low-cost solution to urban transport problems, in the interests of the majority: to compel a reduction of private vehicles, and increase the number of buses and other public transport. However, such a solution would go against a powerful set of class interests, including automobile manufacturers, infrastructure-building firms, and those in their pay. By attributing ‘smartness’ to traffic monitoring and parking devices, these class interests are able to impose a plan that is profitable for them. Similar examples can be given for each sector.

3. The Government claims that digitalisation ‘lowers costs’ by reducing welfare expenditures; but digitalisation often imposes heavy costs on the people. These costs take various forms: wages lost and other costs incurred in order to collect amounts which have been digitally transferred; the costs of a smartphone for a child’s education; the high costs of privatised services in health, education, urban services, and finance; and the multiple costs (paperwork, accounting costs, computer hardware) of GST compliance for small firms. The costs may also take the form of a drastic loss of existing rights or incomes: exclusion from the public distribution system or welfare payments, or the loss of customers for small units which could not afford to join the GST. There is simply no accounting of these costs, so there can be no cost-benefit analysis of digitalisation.

4. We are told that digitalisation promotes ‘transparency’, ‘access’, ‘inclusion’, and ‘empowerment’, but in fact the opposite is the case. There are yawning divisions in the access of different sections of people to digital devices, and in their digital skills. These divisions are along the lines of, and further strengthen, the existing inequalities in India, which is perhaps the world’s most stratified society (by class, caste, community, gender, education, region, age). The existing familiarity of people with various systems of information and administration (e.g., ration books, land records, bank loan documents) can be rendered obsolete at a stroke, making the operations of the State or corporations even more opaque than earlier. People can be more easily excluded from their existing rights. Even those who seemingly possess digital ‘skills’ may only be familiar with certain limited operations, without a comprehension of the system as such. As a result, ordinary people suffer an even greater sense of disorientation, debilitation and dread in relation to the authorities and other powerful parties.

5. A key aspect of the digitalisation project is the conversion of masses of people into atomised entities. In place of social institutions – schools, universities, clinics and hospitals, banks, and so on – we have the digital firm, relating to individual ‘customers’ of education, healthcare, finance, etc. In place of employers relating to the workers of their establishments, we have the fiction of individuals contracting with one another through an app to buy or sell services.

This atomisation runs counter to social needs:

— Students need an academic community, including other students, and a distinct physical location for their studies.

— People need a physical, not virtual, network of health institutions and personnel catering to local communities. Nowhere in the world have public preventive health and curative healthcare been successfully delivered without such a network.

— It was only the Government’s earlier directive to nationalised banks to set up rural branches, and lend to underserved sections, that resulted in some spread of banking services to rural areas and working people.

— Almost all of the problems of the peasantry are common to most peasants, and many of them cannot be addressed individually; they must be addressed collectively. This is so not only for matters relating to pests/disease and the environment; it is even so for market-related issues (e.g., the low prices received by peasants after the harvest).

— Historically, workers have won their rights by uniting as a class against their employers. The atomisation of worker-employer relations is a barrier to their organisation.

Atomisation of the people thus serves the purpose of weakening and dispersing the majority of people, whose only strength lies in their collective organisation.

6. As described above, the Government has invested a large sum in creating the ‘India Stack’ (identity, payments systems, and data exchange), which amounts to a giant subsidy for the corporate sector, by providing free services and free data. It is now creating a separate iteration of that structure for sector after sector: healthcare, agriculture, fintechs, and so on. Each such ‘stack’ requires additional investment by the State, and will collect more data about ‘customers’. Thus digital firms in sector after sector will enjoy subsidies. No accounting is being made of the costs incurred by the State; nor of the value of the data handed over to the corporate sector.

7. The word ‘privacy’, with respect to data, fails to convey what is really at stake; it seems to refer only to the hiding or protecting of personal secrets. A well-known editor characterised privacy as the worry of the “upper-class, wine ‘n cheese, Netflix-watching social media elite” that the Government would snoop on their private lives; by contrast, he asserted, “the poor of this country aren’t impressed by any of this.”37 However, what the editor diverts attention from is the fact that access to personal data increases the power of corporations over people (as well as between one corporation and another). The more a corporation knows about, say, a cultivator’s land, crops, prices paid for inputs and price of sale of produce, loans, routine expenditures, cash requirements, and so on, the greater its ability to dictate terms to that cultivator. Similar would be the case of digital health firm with a patient using a digital health ID, or a loan applicant on a fintech platform. The process of digitalisation is thus greatly strengthening the corporate sector vis-a-vis the people.

8. The digitalisation process has proceeded intertwined with the growth of financialisation.38 People are increasingly pushed to make digital financial transactions in order to receive Government payments; buy fertiliser and other inputs; obtain healthcare or tuitions; send money to their families; sell their labour power or their small-scale production; and so on. In the course of this they are also generating data which is ‘monetised’ by firms. Thousands of ‘fintech’ firms have come up for various financial activities, from borrowing to making payments to investing. Existing financial firms are shifting to digital modes, and digital tech giants like Google and Facebook, using their financial and brand recognition clout, are entering finance. This entire process is creating an economy in which economic activities are increasingly mediated by finance, and finance may become increasingly concentrated.

9. Under the banner of digitalisation, and with repeated invocations of the magic of technology, what is being imposed is an extraordinary class agenda. While private firms are already present or prominent in various sectors, we see now the further withdrawal of the State from these sectors under the assurance that digitalisation will fill any remaining gaps. In this fashion, the ground is being prepared for the phased withdrawal of public healthcare, public education, public sector banks’ lending to the poor, public agricultural extension services, and crop procurement by Government agencies, which are to be substituted by private corporations, and that too in digital form. In the process of ‘formalising’ firms through GST, informal firms are being pushed out of the market. In the name of introducing ‘smartness’, global consulting firms are taking over a swath of policy matters and placing them beyond public scrutiny and agitation. The ‘digitalisation’ of land enables the deletion of various land rights of poor and marginal peasants, and facilitates the transfer of such land to powerful parties. Adorned with a halo of ‘smartness’ and philanthropy, digital sector billionaires are directly intervening in the shaping of policy, and their class agenda in relation to a wide range of sectors is purveyed as unbiased wisdom, beyond questioning by mere mortals. And even as the Indian economy is being further subordinated to imperialism through the process of digitalisation, this fact, and indeed the very term ‘imperialism’, are almost never mentioned in any discussion of the question.

This class agenda is likely to face resistance at various levels (apart from encountering limits imposed by the nature of India’s society and economy). But for this resistance to be successful, it is important for people to recognise the nature of the attack. This collection is a step in that direction.

In closing

We have not attempted to address two questions in this book. First, we have not discussed the use of digitalisation for the purpose of State surveillance of political opponents. Although this is of great significance, it is a subject that has been addressed by many writers. Our aim here has been to focus on different aspects of digitalisation’s impact on India’s economy.

Second, we have not discussed the possible useful applications of digitalisation to India’s economy. This is not because we believe digitalisation can have no useful applications. Quite the contrary; our argument is that it is not ‘technology’ as such that causes the various effects we have described. Rather, it is the specific uses made of that technology by the Indian ruling classes and imperialist interests.

The proponents of India’s digitalisation process have turned to certain longstanding theories of political economists with regard to new technology. To counter the fears of job losses, they put forward the theory of ‘compensation’, namely, the theory that the workers ousted from an industry by new machinery will automatically be re-employed via the growth of the industry making those machines. In the 19th century itself, Marx refuted this by pointing out: “The new labour spent… on the machinery… must necessarily be less than the labour displaced by the use of the machinery; otherwise the product of the machine would be as dear, or dearer, than the product of the manual labour.” Moreover, Marx argued, as workers lose their jobs and wages, demand declines; this results in capitalists cutting production, and throwing more workers out of work. Thus “machinery throws workmen on the streets, not only in that branch of production in which it is introduced, but also in those branches in which it is not introduced.”39 Employment gets reduced both directly, through displacement, and indirectly, through depression of demand. While labour-displacing technology is not the sole reason for the current crisis of employment in India, it is exacerbating it; and the advance of digitalisation would intensify this process.

The digitalisation evangelists also repeat (whether consciously or not) a speculation of J.M. Keynes. In an essay of 1930, Keynes predicted: “In quite a few years – in our own lifetimes I mean – we may be able to perform all the operations of agriculture, mining, and manufacture with a quarter of the human effort to which we have been accustomed.” He was confident that the resulting “technological unemployment” was

… only a temporary phase of maladjustment. All this means in the long run that mankind is solving its economic problem. I would predict that the standard of life in progressive countries one hundred years hence will be between four and eight times as high as it is. There would be nothing surprising in this even in the light of our present knowledge. It would not be foolish to contemplate the possibility of a far greater progress still.40

However, Keynes’s prediction assumes that the benefits of new technology would be distributed evenly throughout society, reducing the hours of toil and sharing its fruits. Due to his class character, he disregarded the question of which class would own and control such enormously productive technology. And consequently he ignored the fact that the capitalist class would deploy new technology to increase its profits by reducing the number of workers and better exploiting and controlling workers, not to “solve the economic problem” of humanity. Indeed, the progress of automation and now digital technology has been accompanied by a steady decline of labour’s share in global income.41 India has experienced growing unemployment/under-employment, stagnating or falling real wages, and the persistence of mass poverty. And the new types of employment linked with digitalisation, such as gig employment, are extremely exploitative.

Digital technology is not magical, contrary to the hype surrounding it; however, like all technological advances made under capitalism, it does increase the productive potential of society. It could be used to decrease the drudgery of certain types of work; it could be used to facilitate various types of collective work; it could even improve the operations of a socialist planned economy (once human beings make choices about the nature of the plan). Indeed, the development of digital technology cries out for a change in production relations in order to realise its potential uses for humanity. That would demand a change of the social order itself. However, in the existing world order ruled by Capital, all these possibilities are stunted, and even turned into their ghastly opposites.

- Press Trust of India, “Bill Gates praises India’s digital public networks, payment systems”, March 1, 2023.footnote ↩︎

- Nandan Nilekani, “India’s digital transformation”, Powerpoint presentation, Slide 29, 2023.https://drive.google.com/file/d/1UK_uvDvLqyELtXAJQA3uRSLDmNjHkxP9/view ↩︎

- World Bank, World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends, p. 2. ↩︎

- Cristian Alonso, Tanuj Bhojwani, Emine Hanedar, Dinar Prihardini, Gerardo Una and Kateryna Zhabska Stacking up the Benefits: Lessons from India’s Digital Journey, International Monetary Fund Working Paper, 2023. ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digitization, accessed April 12, 2024. ↩︎

- Sakshi Awasthy, Rekha Misra and Sarat Dhal, “Cash versus Digital Payment Transactions in India: Decoding the Currency Demand Paradox”, Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers, Vol. 43, No. 2: 2022. ↩︎

- Centre for Advanced Financial Research and Learning (CAFRAL), India Finance Report 2023: Connecting the Last Mile, p. 54. ↩︎

- CAFRAL, op. cit., p. 58. ↩︎

- CAFRAL, op. cit., p. 60. ↩︎

- Website: https://dbtbharat.gov.in/. ↩︎

- Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), A Unique Identity for the People, September 2023, p. 6. ↩︎

- Alonso et al., p. 17. ↩︎

- Ted O’ Callahan, “What Happens When a Billion Identities Are Digitized?”, https://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/what-happens-when-billion-identities-are-digitized ↩︎

- Shishir Sinha, “Aadhaar brought down KYC cost to ₹3 from as high as ₹700, says Nirmala Sitharaman,” Hindu Business Line, April 15, 2023. ↩︎

- Rohin Dharmakumar, Seema Singh and N.S. Ramnath, “How Nandan Nilekani Took Aadhaar Past The Tipping Point”, Forbes, October 8, 2013. ↩︎

- Wada Na Todo Abhiyan, Citizens’ Report on four years of the NDA Government 2014-2018, p. 5. ↩︎

- As of April 2024 – https://pmjdy.gov.in/account. ↩︎

- According to the dominant theory, freely fluctuating prices play a key role in a market economy, sending signals of what and how much to produce. ↩︎

- Economic Survey 2014-15, vol. I, p. 64. ↩︎

- However, when the advanced countries suffer crises, such as in 2008 (the Global Financial Crisis) or 2020 (the Covid crisis), they abandon neoliberal theory, and their governments apply massive fiscal and monetary stimulus to revive their economies. Nevertheless, the same advanced countries and their intellectual armies press uninterrupted neoliberal theory on receptive Third World countries like India; thus the Indian government kept a lid on its spending even during the Covid lockdown. ↩︎

- Alonso et al. ↩︎

- Nandan Nilekani and Tanuj Bhojwani, “Unlocking India’s potential with AI”, Finance and Development, IMF, December 2023. ↩︎

- “Cash ban will help accelerate services industry: Nilekani”, Times News Network, December 8, 2016. ↩︎

- Alonso et al., p. 6. ↩︎

- Narendra Modi, ‘Mann ki Baat’, December 25, 2016. ↩︎

- Sangeeta Ghosh, “Formalising the Informal through GST: Evidence from a Survey of MSMEs”, Review of Development and Change, 2022. ↩︎

- “Imagine an India without hawkers”, Economist, January 5, 2023 https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/01/05/imagine-an-india-without-hawkers ↩︎

- CAFRAL, op. cit., p. 65. ↩︎

- Ankita Sharma and Hindol Sengupta, “Covid-19 has accelerated India’s digital re-set”, August 5, 2020, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/08/covid-19-has-accelerated-india-s-digital-reset/ ↩︎

- Krishnamurthy Subramanian, quoted in “Digitisation: Driving India’s economic growth engine,” September 27, 2021, https://www.forbesindia.com/article/brand-connect/digitisation-driving-indias-economic-growth-engine/70655/1 ↩︎

- Bill Gates, “Making the world’s invisible people, visible”, Gates Notes, January 29, 2019, https://www.gatesnotes.com/Heroes-in-the-Field-Nandan-Nilekani ↩︎

- Eram Tafsir, “Nandan Nilekani lays out digitisation, Aadhaar, GST benefits; says, direct benefit can revive power sector”, Financial Express, April 23, 2019. ↩︎

- Jean Dreze, “The Aadhaar coup”, The Hindu, September 6, 2016. ↩︎

- Anirban Sarma and Shrushti Jaybhaye, “Edtech in India: Boom, bust, or bubble?”, Observer Research Foundation, January 24, 2024, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/edtech-in-india-boom-bust-or-bubble ↩︎

- Hussain Indorewala, “The Toll-Booth City: Notes on ‘Smart’ Urbanism”. ↩︎

- Mohamed Elassy, Mohammed Al-Hattab, Maen Takruri and Sufian Badawi, “Intelligent transportation systems for sustainable smart cities”, Transport Engineering, April 14, 2024. ↩︎

- Shekhar Gupta, “God, please save India from our ‘wine ‘n cheese’ Aadhaarophobics”, The Print, September 25, 2018. The article makes the disclosure that Nandan Nilekani is one of the investors in The Print, along with other tech entrepreneurs. ↩︎

- There is no commonly accepted definition of financialisation. Here we use it to indicate the growing importance of financial markets and financial activities in the economy, share of the financial sector in national income, and weight of financial capitalists in the ruling class. ↩︎

- Karl Marx, Capital, vol. I, Chapter 15, Section 6: The Theory of Compensation as Regards the Workpeople Displaced by Machinery.” Moscow: Progress Publishers. ↩︎

- John Maynard Keynes, “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren (1930),” in Essays in Persuasion, Harcourt Brace, New York, 1932, 358-373. ↩︎

- International Labour Organization, “World Employment and Social Outlook: September 2024 Update”. ↩︎