No. 52, June 2012

|

No. 52, June 2012 |

|

|

No. 52 Behind the Present Wave of Unrest in the Auto Sector Union Budget 2012-13: Gifts for Private Capital, Thefts from the Working People The Political Economy of Corporations: Behind the Veil of ‘Corporate Efficiency’ |

Union Budget 2012-13 At the start of this year’s Budget speech on March 16, Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee spelled out his world-view:

For all his labours, he may not succeed in his fond wish: his Budget appears to have left Capital restless, and the share market promptly signalled its disappointment with a 200-point dip. Given the sort of sweeping demands being made by foreign investors, Indian big business and their lapdog media in the run-up to the Budget, it would have been almost impossible for the Finance Minister to have satisfied them. And, having just suffered humiliating defeats in the U.P. and Punjab elections, the UPA government could hardly afford to trumpet the pro-‘reform’ (read: pro-Capital and anti-people) nature of this Budget. But a closer examination of the Budget reveals that it is in fact packed with hand-outs for Capital and thefts from the working people. The following are the headlines:

Below are the details: (i) Redistribution by Taxes According to the Finance Minister,

This is rather unfair to Hamlet; he, whatever his other flaws, did not propose to be cruel to one class of people in order to be kind to another. The Finance Minister says bluntly: “My proposals on Direct Taxes are estimated to result in a net revenue loss of Rs 4,500 crore for the year. Proposals relating to Indirect Taxes are estimated to result in a net revenue gain of Rs 45,940 crore, leaving a net gain of Rs 41,440 crore in the Budget”. Direct taxes are paid by the wealthy and the corporate sector; indirect taxes, such as excise and service tax, fall on everybody, even the poorest, and thus snatch away a disproportionate share of the income of the poor. The Budget extends service tax to all services except a short negative list, and it raises the standard rate of excise duty from 10 per cent to 12 per cent. As a result, revenues from service tax are projected to rise by 30.5 per cent, or Rs 29,000 crore, and excise duty by 29.1 per cent, or Rs 43,654 crore. The sum of the two increases is over 0.7 per cent of GDP. Of course, the money for Government expenditure has to come from somewhere. It is worth noting here that India’s government revenues (Centre, states, and municipalities) are just 17.6 per cent of GDP – which, as the Economic Survey notes, is “one of the lowest in emerging economies and certainly very low vis-a-vis the advanced economies”. The corresponding figures for Brazil, Russia, China and South Africa are 37.5, 35, 20.4 and 27 per cent, respectively, while the average for the advanced economies is 35.9 per cent. Does India lack sources of direct tax revenue? Hardly. It is now well-known that the corporate sector and well-off income tax payers receive subsidies (in the form of tax concessions); the latest Budget estimates the revenue forgone on direct tax concessions at Rs 94,000 crore last year. But this is only the tip of the iceberg. There is plenty of evidence that India is among the world’s most unequal countries. For example, take the discrepancy between the two official estimates of household consumption: One is based on a house-to-house survey that fails to record the consumption of the rich; it is less than half the estimate of household consumption in the National Accounts Statistics, and the gap is getting wider every year. Even recent studies by the World Bank and the IMF observe that this suggests massive inequality1 A more popular measure is the wealth of India’s dollar billionaires, put at nearly a quarter of India’s GDP.2 Studies by private research firms put the combined wealth of India’s “High Net Worth Individuals (HNWIs)” – who make up less than .01 per cent of the population (i.e., less than one out of every 10,000 people) – at between one-third and a half of India’s GDP.3 Those measures are only of the licit assets of the HNWIs. According to another recent study4, the post-1991 programme economic ‘reform’ “itself had a negative impact on illicit flows in that liberalization of trade and general deregulation led to an increase in illicit flows rather than their curtailment.” It links the accelerating illicit outflows to the worsening distribution of income in India: “A more skewed distribution of income implies that there are many more high net-worth individuals (HNWIs) in India now than ever before. Based on the capacity to transfer substantial capital, it is the HNWIs and private companies that are the primary drivers of illicit flows from the private sector in India (rather than the common man). This is a possible explanation behind our findings that the faster rates of growth in the post-reform period have not been inclusive in that the income distribution is more skewed today, which in turn has driven illicit flows from the country.” The study notes that “While the underground economy the world over often involves illegal activities, in India even legal businesses and the Government contribute to it.” Based on an estimate that the black economy in India is 50 per cent of India’s GDP, the study estimates that, of that sum, 72 per cent, or $462 billion, was held abroad. There is no prospect of retrieving that sum, but what is significant is that the illicit flow of funds continues, and has accelerated in the last decade. Rather than lay its hands on the vast wealth of the HNWIs, the rulers prefer to fill their coffers from the labouring people. (ii) Attack on Fuel, Fertiliser and Food Subsidies The words “poverty” and “unemployment” are not to be found in the Budget speech; these phenomena do not seem to trouble the finance minister in the least. Nor does the Rs 94,000 crore in revenue forgone in tax concessions last year to the corporate sector and the well-off. But he is troubled: as he confessed last month, “when I think of the enormity of the subsidies to be provided, I lose my sleep”. Those whose opinions count – the corporate sector and “restless global capital” – have been demanding more stridently than ever that the fiscal deficit (i.e., the Government’s borrowings) must be brought down drastically by slashing subsidies. All the cuts in subsidy are justified with the reigning theology, or rather mental illness, which separates the well-being of the “economy” from the productive well-being of the people. The “economy” is something which floats about independently of those who work it and earn their bread from it; it can soar even as the people plunge into the abyss. This pathological inversion of thought (which Marx called ‘reification’) is reflected, for example, in Mukherjee’s assurance that he intends to keep slashing subsidies for the next three years:

Apparently, the media have not noted the implication of the above statement. Without fanfare, Mukherjee has announced a very major policy measure: Irrespective of the effect on the people, subsidies will be cut. Similarly, the fertiliser subsidy has been cut by 10 per cent, or nearly Rs 7,000 crore. The Budget speech contains two major indicators of the Government’s plans with regard to fertiliser. First, the Finance Ministers declares he will implement the recommendations of the Nandan Nilekani task force for direct transfer of fertiliser subsidy. Subsidy will be transferred in the first phase to fertiliser retailers, and later to over 120 million farmers. Secondly, the Government “has taken steps to finalise price and investment policies for urea”; what this means, in plain English, is that the Government has decided to allow the free pricing of urea, in order to attract private investors to set up fresh urea capacity. Urea is the only one of the three major fertilisers for which the Government still fixes the price, and its price has therefore not risen; thanks to the deregulation of April 2010, potassium and phosphatic fertilisers are already priced freely, leading to a doubling of their prices and an absolute fall in their consumption. In a later note, we will explain how Nilekani’s gargantuan bureaucratic scheme, as well as the license to fertiliser producers to charge “what the market will bear”, are certain to wreak havoc in India’s small-peasant agriculture. The food subsidy has been allocated only 3 per cent additional funds (over the Revised Estimates for 2011-12). This despite the Government’s claim that it will roll out its much-trumpeted National Food Security Act soon. Merely to maintain the public distribution system at the same real level (taking into account the Food Corporation’s rising costs and a probable rise in crop procurement prices next year), a hike of at least 10 per cent would have been called for. In that sense, the Budget 2012-13 figure amounts to a cut of at least Rs 5,000 crore. No doubt, the Finance Minister clarified that he will later make additional funds available for the implementation of the Act, but what prevented him from providing for it in the Budget? Rather, the derisory figure in the Budget is an indication of what lies in store. We shall see below, in the case of the rural employment scheme, that such ‘demand-based’ schemes give the Government to slash expenditure. (iii) Cut in Funds to Agriculture On the face of it, it appears Mukherjee has hiked the allocation to the Ministry of Agriculture by 20 per cent. But this is an annual ruse: A much-trumpeted hike in one head of expenditure is compensated for by reductions in other, related expenditure. Taking together the various heads of expenditure related to agriculture (Ministry of Agriculture, fertiliser subsidy, agricultural financial institutions, Integrated Watershed Development Programme, and Ministry of Water Resources), the total amounts to a 1.4 per cent increase over 2011-12. It is only 8.8 per cent higher than the expenditure of two years ago, in 2010-11. Given the 9 per cent-plus inflation rate in both years, real spending on agriculture has fallen considerably. (iv) Rural Employment in Decline That most-trumpeted scheme of the UPA government, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, is being hollowed out. According to the latest Economic Survey, 2.84 billion person-days of employment were generated under the MGNREGS in 2009-10, at the peak of the scheme; this fell in 2010-11 to 2.57 billion person-days. The Government estimates that expenditure during 2011-12 on NREGS was Rs 38,000 crore. This level of expenditure would have funded 2.2 billion person-days of employment, i.e., a further fall.5 This is a drop of 21 per cent in two years. In fact, National Sample Survey data indicate that, even at its peak in 2009-10, the MGNREGS generated around 43 per cent less person-days of employment than officially claimed, but now even the official figure is in decline. (v) Welfare Expenditure – Trivial Rise in Real Per Capita Terms Taking a very broad definition of welfare expenditure (the Ministries of Health; Education; Labour & Employment; Development of the Northeast; Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises; Minority Affairs; Panchayati Raj; Rural Development – including schemes for rural employment, rural housing, and rural roads; Drinking Water & Sanitation; Social Justice & Empowerment; and schemes for handlooms and rural electrification), there is a 19 per cent hike over the expenditure in 2011-12 – from Rs 206,402 crore to Rs 245,658 crore. This turns out to be less impressive than it seems, because it is on a low base. Not only was the Budget for 2011-12 miserly, but in the course of 2011-12 the Government failed to spend even the budgeted figure. How much of an increase is welfare expenditure in the 2012-13 Budget over the figure two years ago? The Budget 2012-13 figure for the sum of all these expenditures is thus 25.8 per cent over the actual expenditure of 2010-11; but once you strip out price rise6 and population growth7, the real rise in per capita expenditure is very slight. More importantly, the UPA government’s “Common Minimum Programme” of May 2004 stated that “The UPA government pledges to raise public spending in education to least 6 per cent of GDP with at least half this amount being spent of primary and secondary sectors.... The UPA government will raise public spending on health to at least 2-3 per cent of GDP over the next five years with focus on primary health care.” Eight years later, as the latest Economic Survey shows, there has been virtually zero progress in this direction. The targets are as far away as in 2004. Even the budgeted figure for the (combined Centre and states) expenditure on education in 2011-12 was only 3.1 per cent of GDP, and as we now know the Central expenditure fell far short of the budgeted figure. The combined budget of the Centre and states for health in 2011-12 was an appallingly low 1.3 per cent of GDP, with the overwhelming burden borne out of pocket by the people. (In fact, the lower the share of public expenditure in total health expenditure, the higher is the share of GDP spent on health, and the worse the health outcomes. In other words, when the Government doesn’t spend on public health, the unchecked private sector bloats total medical expenditure, and people wind up getting worse health care.) (vi) Government Spending Falling as a Percentage of GDP There is a deafening chorus among the ruling class media and economists-for-hire that the Government must cut its expenditure and thus bring down the fiscal deficit. For a moment, let us swallow their theory that a fiscal deficit – which is nothing but Government borrowing – is a bad thing in the present circumstances. Even so, their silences and omissions are revealing of their class bias. The fiscal ‘hawks’ do not talk of bridging the deficit by increased direct taxation. As we noted earlier, there is not so much a shortage of wealth in the country as a shortage of desire among the rulers to tax it. Far from reducing Government expenditure, in every field of life one finds the need to expand it. There are far too few teachers; health workers; railway safety staff; agricultural extension workers; and so on. The widespread propaganda that there are too many Government employees has no relation to reality. Total employment in Central and state public sector community, social and personal services has remained virtually the same (about 9 million) between 1991 and today, despite the fact that the population has risen from 846 million to 1210 million. This drive to reduce Government expenditure is simply a drive to suppress the working people’s share in the social product. In some cases, starving Government departments of funds has an even more direct class rationale. To take one example: the Indian Bureau of Mines, which is meant, among other things, to monitor illegal mining throughout the country and prosecute the offenders. It is by now well known that tens of thousands of crores worth of minerals are being illegally mined in the country. For example, more than 30 million tonnes of iron ore, worth nearly $3 billion, were illegally mined in Karnataka in less than five years, according to official figures. The entire operation was carried out in a systematic fashion, largely by corporate firms. How large is the budget of the Bureau of Mines, only one of whose activities is to check illegal mining? Rs 65 crore, or $13 million. It is unlikely that such a budget would suffice to check illegal mining even in a single state. The paltry budget of the Ministry of Environment and Forests, which is lower in real terms (i.e. after discounting for inflation) than the actual expenditure of 2010-11, is in line with the same policy. The only wings of Government which keep expanding employment are the military and police (incidentally, these too are included in “community, social and personal services”). However, the fiscal ‘hawks’ do not utter a word against the military and police budgets, or what is called ‘national security’ expenditure (security of the ruling classes, insecurity of the Indian people and of weaker regional states). In India’s case, such expenditure amounts to 3.7 per cent of GDP even without taking into account hidden military expenditures8 In fact, India’s general government expenditure (including that of the Centre, states and municipalities), as a percentage of GDP, is very low by comparison not only with the advanced economies but also with other major developing countries. In comparison to India’s 26 per cent, the governments of advanced economies spend an average of 43.3 per cent of their GDP, and even Brazil spends 40.4 per cent. China, no doubt, has a lower ratio than India, but that is hardly a healthy example to follow.

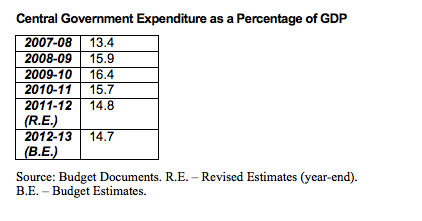

True, India’s (general government) fiscal deficit is larger than most of the other countries in the table, but it is less than that of the US, UK, and Japan, and not far from the average for the advanced economies – the very countries that preach to India the virtues of fiscal austerity. The financial oligarchy worldwide has no problems with large fiscal deficits if they are necessary in order to bail out the financial sector. Once they have recovered, the financial oligarchs turn their guns on the fiscal deficit, unmindful of the fact that the rest of the economy is still in a depression.  In fact, despite the fact that the economy has clearly been slowing down, the Government is trying to reduce its expenditure even further, thus contributing to the slowdown. Thus Central Government expenditure as a percentage of GDP has been falling every year since 2009-10. If the Government is not going to stimulate the economy, where will growth come from? At the outset of his Budget speech, the Finance Minister said one of his main objectives would be to “Create conditions for rapid revival of high growth in private investment”. Indeed that is the crux of the Budget – to provide attractive incentives to the private sector, in the hope that it will invest and revive growth. For example, fertiliser prices are to be deregulated in order that private investment in the fertiliser industry grow. Petroleum prices are to be raised to solicit private investment in the petroleum sector. The scheme of “Viability Gap Funding” (in plain English, a subsidy to the private corporate sector) is to be extended to new sectors in irrigation, capital investment in fertiliser, terminal markets, common infrastructure in agricultural markets, soil testing laboratories, oil and gas/LNG storage facilities, oil and gas pipelines, fixed network for telecommunication and telecom towers. The slashing of subsidies is necessary partly in order to save the Government’s revenues for worthier causes such as tax benefits for the fat cats. But further, private investors want the Government to stop regulating the prices of commodities, in order that private firms have a free hand in pricing these commodities – whatever the consequences for the vast majority. When the Government recently prevailed on Coal India to roll back a steep price hike, a foreign investor (with a 1 per cent share in Coal India, as against the Government’s 90 per cent stake) threatened legal action against the Coal India board. Citigroup tells us in a recent research report that the hikes we have seen in electricity tariffs in 16 states aren’t enough; tariffs need to be raised another 45 to 60 per cent. Further, the Finance Minister promises, as one of his main objectives, to “Address supply bottlenecks... particularly in coal, power, national highways, railways and civil aviation.” Every reader of the newspapers knows what this means: sidelining or crushing the protests of peasants, slumdwellers, and environmental activists regarding the forcible acquisition of land and wanton environmental destruction. The corporate sector has quite openly been calling for these “bottlenecks” to be dealt with swiftly. The Budget also reiterates the UPA Government’s promise to multinational giants such as Walmart, Tesco, Carrefour and Metro to allow them into multi-brand retail, despite the nationwide opposition from millions of small retailers. Further, it indicates that the Government will soon allow foreign direct investment (FDI) by foreign airlines in Indian airlines – or, to put it more bluntly, the foreign takeover of Indian civil aviation. (vii) Soliciting Hot Flows The past year has seen the emergence of an potential crisis on the foreign exchange front. On the face of it, with foreign exchange reserves of $311.5 billion at the end of September 2011, enough to pay for eight months’ imports, why should there be cause for worry? And yet, with the onset of the euro crisis, which would have an impact on foreign capital flows in and out of India, the rupee began to slide from the end of July 2011. The stock market, driven by foreign investors, plunged. Currency speculators found ingenious ways to get around restrictions on speculation on the rupee’s value. The rupee fell from a peak of Rs 43.94 per US dollar on July 27, 2011 to a low of Rs 54.23 per US dollar on December 15, 2011 – a drop of 19 per cent. In a panic, the Government relaxed restrictions on external commercial borrowings (ECBs), raised the ceiling on foreign institutional investors’ (FIIs’) investments in government securities and corporate bonds (to an overall limit of $60 billion), relaxed the rates on non-resident deposits in Indian banks, and took certain regulatory steps against speculation in the rupee’s value. Discarding the earlier stipulation that only financial entities regulated abroad (“Foreign Institutional Investors”) could invest in India’s share markets, the Government now allowed investment by so-called “Qualified Foreign Investors” (QFIs) – essentially any individual, association or group from a foreign country compliant with standards set by an international grouping called the Financial Action Task Force. This was an open invitation to all sorts of shady funds. What stopped the panic, however, the European Central Bank’s decision to hand out to Europe’s banks massive funds at near-zero rates – $641 billion in late December 2011, followed by $713 billion at the end of February 2012. The sea of fresh liquidity from abroad put a temporary stop to the panic, and the rupee revived by January 31 to Rs 49.67 per US dollar; the Indian stock market revived. The slide in economic activity began to slow; the Economic Survey notes that there are signs that “the weakness in economic activity has bottomed out and a gradual upswing is imminent”. So ‘globalised’ is the Indian economy that events in Europe can swing it back and forth like a toy, within the span of a few months. On closer examination, it emerges that India’s giant foreign exchange reserves are composed of hot flows and short-term debt. At the end of June 2011, they stood at $315.7 billion. But short-term debt by “residual maturity”, i.e., all debt maturing within a year, had risen to 43.5 per cent of the reserves (in March 2010, this figure stood at 38.7 per cent). Accumulated portfolio investments by original valuation (i.e., their value at the time they entered) stood at 45.8 per cent of reserves in June 2011 (39.5 per cent in March 2010); of course, their market value today would be much higher. In brief, the reserves are made of sand. The crisis of the second half of 2011 has now passed; but any fresh crisis half-way round the world is liable to send the reserves into decline and the rupee plunging. The Budget moves further along the path of opening up to foreign flows of all types. It allows QFIs to invest in India’s corporate bond market; permits external commercial borrowings (ECBs) for the power, roads, airlines, and real estate (“affordable housing projects”). All these, in particular power, airlines and real estate, have been in serious financial trouble recently, and have problems servicing their large borrowings from Indian banks. If they are able to borrow abroad, it will be at high interest rates. It is worth noting that ECBs’ share of external debt has been rising, from 27.1 per cent in March 2010 to 30.3 per cent in September 2011. The Budget also drastically cuts withholding tax on interest payments on ECBs for power, airlines, roads and bridges, ports and shipyards, “affordable housing”, fertiliser, and dams. Even as he tries to entice more hot flows into the country, the Finance Minister takes a further step to allow funds to flow out of the country. The Budget permits “two-way fungibility in Indian Depository Receipts” (IDRs). IDRs are funds raised by foreign firms in India, with each IDR being equivalent to a certain number of shares of the foreign firm. The present step would allow IDRs to be swapped for the underlying shares listed on foreign share markets. In other words, it would facilitate investment in foreign share markets by Indians. This is a further step down the road to capital account convertibility, making India even more vulnerable to volatile flows of capital. Volatile world, restless people This brings us back to what Pranab Mukherjee has taken as the theme for this Budget: to make India “a source of stability for the world economy and provide a safe destination for restless global capital.” What is significant, however, is Mukherjee’s view of his “high table responsibilities”: namely, to “provide a safe destination for global capital”. Even had he been successful in this endeavour, that success would have yielded nothing for the people of India, who apparently do not figure in his scheme of priorities. The Indian people may not find their own country a “safe destination”; malnutrition, disease and usurious debt claim their lives, and even the survivors often lack such luxuries as drinking water and toilets, let alone decent employment. However, unlike “restless global capital”, they do not have the option of exiting India for safer destinations. The crushing burdens being placed on them, however, do make them even more restless to change the present social order.

Notes: 1. Perspectives on Poverty in India: Stylized Facts from Survey Data, World Bank, 2011; “Inclusive growth”, India: Selected Issues, International Monetary Fund, February 2008. (back) 2. World Bank, op. cit. (back) 3. For example, see Asia-Pacific Wealth Report 2010, Capgemini and Merrill Lynch Wealth Management, and Top of the Pyramid: Decoding the Ultra High Net Worth Individual, 2011, Kotak Wealth and CRISIL Research, 2011. (back) 4. Dev Kar, The Drivers and Dynamics of Illicit Flows from India, 1948-2008, November 2010. (back) 5. According to the Economic Survey 2011-12, as of January 19, 2012, Rs 21,125 crore had been utilised, generating 1,224 million person-days of employment. At this rate, Rs 38,000 crore would have generated 2.2 billion person-days. (back) 6. About 19.6 per cent over the two year-period. (back) 7. About 2.7 per cent over the two-year period. (back) 8. We have taken the actual defence and police expenditures of the Centre in 2010-11, and the state budget figures for police in 2010-11. Hidden military expenditures are quite large: they are to be found in the space programme, the nuclear programme, and the construction of roads for national security purposes. (back)

NEXT: The Political Economy of Corporations:

Behind the Veil of ‘Corporate Efficiency’

|

|

| Home| About Us | Current Issue | Back Issues | Contact Us | |

|

|

All material © copyright 2015 by Research Unit for Political Economy |

|